Jasenovac Concentration Camp stands as one of the most horrifying sites of World War II, a chilling testament to human cruelty. It was located in the Independent State of Croatia, an ally to Nazi Germany during the conflict. The concentration camp was designed for the systematic extermination and total annihilation of Serbs, Jews, Roma, and other anti-fascists, a dark testament to the genocidal intent that underscored its operation.

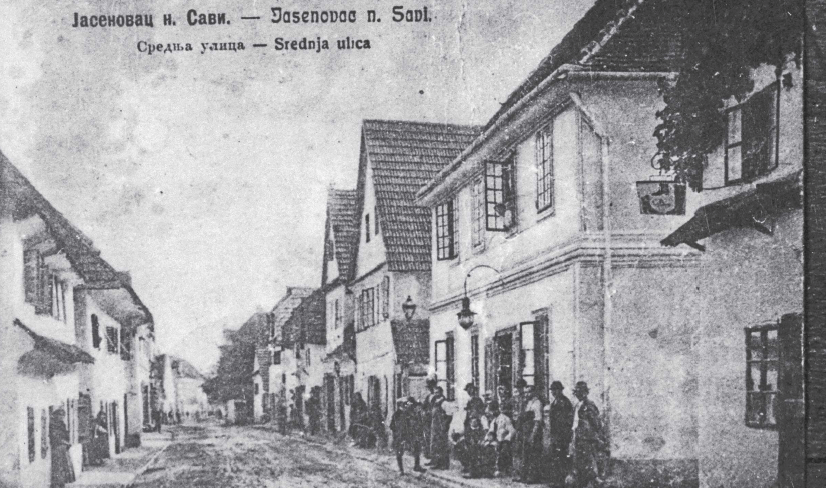

Jasenovac, before World War II

Jasenovac, a village on the Sava River’s left bank, was a bustling community between the world wars. It boasted two river piers, around thirty craft shops, a handful of stores, two hotels, and even a cinema, home to over 2,000 residents. In 1929, the Bacic family, specifically Lazar Bacic, his brother Jovan, and Jovan’s sons, Ozren and Uros, established the “Traffic fellowship”. This industrial complex, which greatly contributed to the village’s development, included a brickyard, chain factory, motor mill, sawmill, blacksmith, locksmith, carpentry, electrician’s workshop, paintwork, upholstery, loophole, and auto repair shop. During summer, Bacic’s brickyard and chain factory could employ up to 3,000 seasonal workers.

The Establishment of Jasenovac Concentration Camp

Under Vjekoslav Maks Luburic, the Office of the third Ustasha Surveillance Service governed all camps in the Independent State of Croatia. Due to Italian pressure, the Ustasha moved camps out of Italy’s sphere of influence, leading to the closure of the Jadovno camp in mid-August 1941. Lonja field, in the German influence zone and nearby the rivers Sava and Strug, was chosen for a new camp. Its location facilitated the quick and easy transportation of the Serbian population from connected regions like Potkozarje, Banija, and Western Slavonia.

The first detainees arrived in Jasenovac in August 1941. Under the guise of a public works project to drain Lonja field, a concentration camp was established outside the village of Jasenovac in Bročice and Krapje. There were between 4,000 and 5,000 prisoners in these two camps who worked on the construction of an embankment along the Strug River. In these initial camps, prisoners lived in congested conditions and worked on the construction of an embankment along the Strug River.

The harsh conditions of constant rainfall and daily prisoner beatings exacerbated the grim environment within the camps. Casualties, resulting from these brutalities, were promptly interred within the embankment. The severity of the autumn floods in mid-November 1941 led to the closure of both concentration camps. A fraction of the prisoner population, approximately 1,500 individuals, were transferred to the newly established Camp III, Ciglana. The remaining detainees were killed.

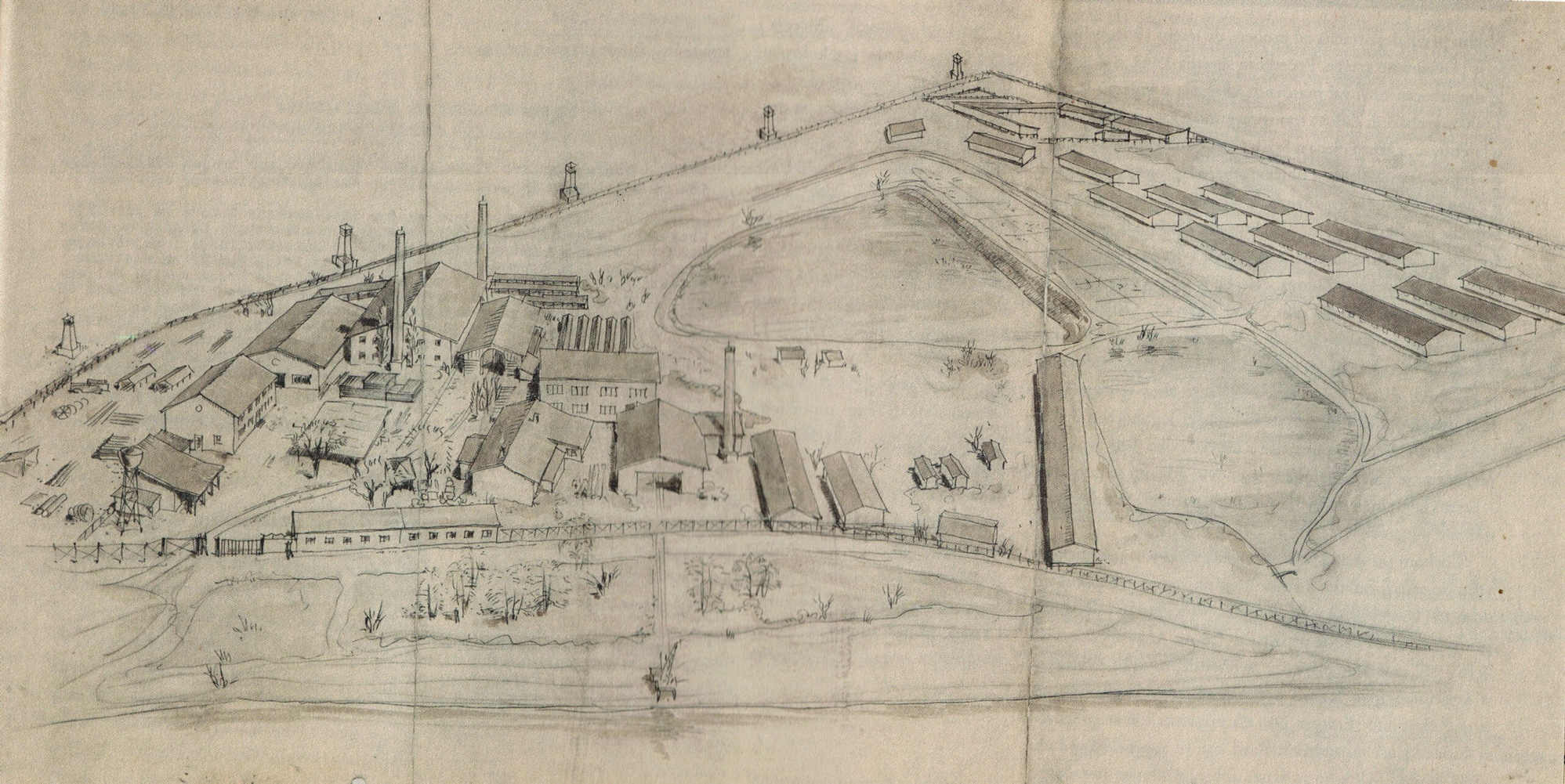

Concentration Camp III, or Camp III – Ciglana (Brickworks), was established on the 125-hectare estate of the Serbian Bačić family near the Jasenovac settlement on the Sava River’s bank. A decision by the Presidency of the Independent State of Croatia’s Government in October 1941 resulted in the vast, valuable Bačić estate being taken over by the Ministry of Interior and the Directorate for Public Order and Security. As the largest and longest-standing camp in the Jasenovac system, Camp III was initially surrounded by barbed wire but later walled by prisoners on three sides, with the Sava River acting as a natural barrier.

The railway line, constructed in 1899 for river dock and later industrial use, led directly into the camp, transporting many of its prisoners. Detainees were housed in primitive barracks, and despite the construction of new barracks and a hospital in 1942 for international inspection, conditions remained deplorable. Overcrowding and appalling hygiene led to regular typhus outbreaks, prompting a disinfection department only when guards began falling ill. Though this did not eliminate typhus, epidemics became less frequent.

Camp IV, known as Kožara, and Camp V, or Stara Gradiška, represented two distinct yet equally horrific chapters in the history of the Jasenovac concentration camp system.

Kožara was primarily a transit camp, a grim waypoint for prisoners destined for the lethal camps further within the system. The camp’s deplorable conditions and meager provisions often resulted in fatalities even before the detainees reached their final destination. Illness and malnutrition were rampant, and the temporary nature of the camp offered little in terms of shelter or basic amenities, exacerbating the prisoners’ suffering.

Stara Gradiška, on the other hand, was one of the most brutal camps in the system. Infamous for its inhumane living conditions and the high mortality rate among its inmates, it primarily held women and children. The camp, housed within an old Austro-Hungarian fortress, was a site of severe mistreatment and torture. Despite its grim reputation, some inmates remarkably managed to survive and later share their harrowing experiences, providing invaluable insights into the grim realities of life in the camp.

Crimes in Jasenovac Concentration Camp and the Difficult Life of the Prisoners

Prisoners in the Jasenovac camps performed grueling tasks under appalling conditions. In the brickworks, they labored in water and mud to excavate earth for bricks. The resultant body of water, contaminated by the bodies of the liquidated, was their sole source for drinking, cooking, and bathing, leading to rampant typhoid fever.

In Lančara, a hardware factory, skilled prisoners produced chains and weapons for the Ustashe, which insulated them slightly from the frequent liquidations. A civil-engineering group was responsible for building camp structures and a protective embankment, often embedding the bodies of the deceased in their works.

Electricity for the camp and Jasenovac village was generated by burning timber, which was also harvested by prisoners. The forest group faced a high risk of being killed during or after their work.

In 1943, a female camp was established with about 1,000 women working in fields and orchards in the camp’s surroundings. Another work group handled various tasks both inside and outside the camp, including transferring oil and unloading food supplies.

Despite the long, hardworking days, prisoners were malnourished, which weakened them and made them susceptible to diseases. Hunger was a constant companion, leading to strategies for rationing and hoarding food. Brief reprieves came when prisoners were allowed to receive food packages from home, though these were heavily censored and pilfered by the Ustashe before being given to prisoners.

Upon arrival at Jasenovac, prisoners would typically be tortured and abused, often in the Bačić family house used as Ustasha headquarters. Upon entering the camp, they were met by violent “welcoming” committees and were robbed of any valuable possessions. These initial experiences were terrifying, made worse by random selection events (“performances”) where Ustashas would arbitrarily choose prisoners for execution.

Daily life in the camp was filled with constant fear as individual or mass killings were commonplace. Prisoners were murdered for trivial reasons such as an incorrect glance or just being at the wrong place at the wrong time, or even due to an Ustasha’s bad mood. Initially, executions were carried out near the camp and involved shooting, but as the camp expanded, methods became more gruesome, utilizing axes or knives, and the executions were moved to the riverbank.

In terms of the level of violence, brutality, and the number of victims, Jasenovac ranks among the largest concentration camps in Europe during World War II, surpassed only by Auschwitz and Treblinka. However, the horrifyingly brutal methods of torture and killing used at Jasenovac set it apart for its barbarity.

One of the testimonies that describes the horrors of Jasenovac comes from Djordje Milisa from Sibenik, who stated: “I saw just before Christmas 1941 when a group of 500 detainees were taken to the wasteland. They were first forced to dig a deep pit. After that, the Ustashas hit them one by one over the head with sledgehammers, threw them into the pit, buried them and spread lime on top. This was happening at a distance of several hundred meters away from me and the other prisoners, so I couldn’t see or recognize the individual bloodthirsty murderers. I know that the group that was killed were all Serbs. At the time, the commander of Jasenovac was Ljubo Milos.”

The Breakout of Jasenovac Prisoners and the End of World War II

In April 1945, the Ustashas initiated the final liquidation of the Jasenovac concentration camp, a process involving the murder of all remaining prisoners, destruction of camp archives, and burning of camp buildings. Crucially, an operation to conceal the traces of crimes perpetrated in Jasenovac commenced. From the 6th to the 20th of April, prisoners were forced to dig up graves, remove the remains of victims, and burn them, with the ashes being either thrown into the Sava River or buried. Every day, a new group of prisoners was sent to this task, as the previous group had been killed.

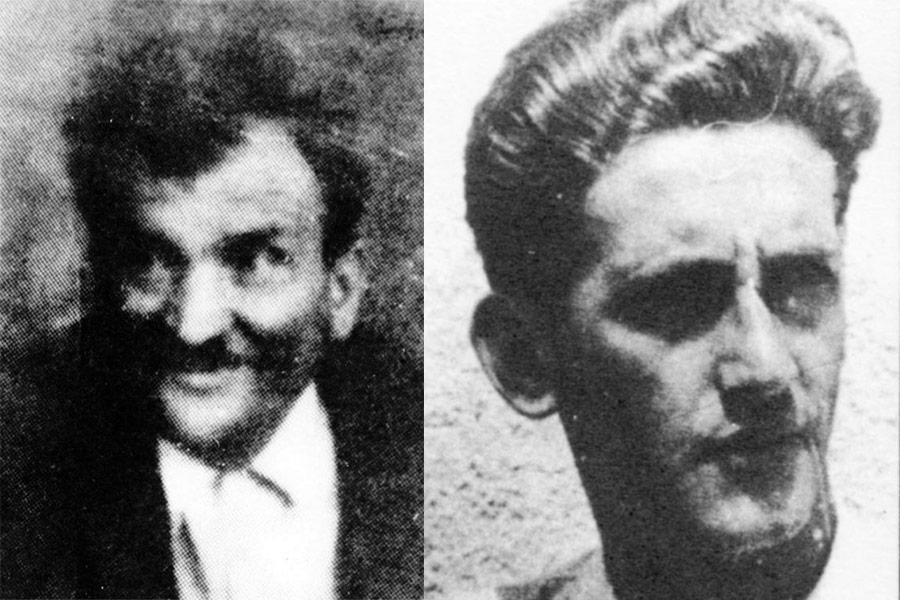

On the afternoon of April 21, the remaining prisoners decided to attempt a breakout. Ante Bakotić, leader of the work group of chemists, was chosen to signal the start of the escape. On Sunday, April 22, 1945, at 09:50, the signal was given. Armed with bricks and boards, the prisoners stormed the building door, overpowering the guards. Approximately 600 prisoners ran from the building; the rest, too ill or infirm, could not join the breakout.

A key figure in the escape was Mile Ristić. Grabbing a machine gun from the Ustashas, Ristić neutralized a bunker by the gate, enabling the prisoners to escape the camp confines. Furthermore, prisoner Edo Šajer climbed a pillar and severed telephone lines, preventing the Ustashas from calling for backup. Their heroism ensured the survival of 90 prisoners who managed to hold out until the arrival of Yugoslav Army units.

Later that day, a breakout also took place from Camp IV Kožara, resulting in 12 survivors. At Stara Gradiška camp, anticipating the arrival of partisans, the Ustashas began liquidating the camp. Some prisoners managed to escape by jumping over the camp wall, while others hid in the camp buildings and attics.

After the breakout, Ustashas remained in the Jasenovac area for a few more days, mining and pulling down the camp buildings and killing any remaining prisoners. The Yugoslav Army arrived in the deserted Jasenovac settlement and the devastated camp on May 2, 1945, with the task of preserving all evidence of the crimes until the arrival of the State Commission for Determining Crimes of Occupiers and Their Collaborators.

In total, 169 prisoners managed to survive the Ustasha liquidation of the Jasenovac Camp System. These included survivors from the breakouts from the Ciglana and Kožara camps, those who managed to hide or escape from the Ciglana camp, survivors from the Ustasha hospital, the mechanical workshop, the investigation prisons, the camp farms, and the Stara Gradiška concentration camp. In the mid-1950s, the area of the former camp was marked by the municipal organization of SUBNOR from Jasenovac, marking the start of an organized effort to memorialize the victims of the Jasenovac concentration camps.

The Number of Victims in Jasenovac and the Importance of Remembering

The question of the number of victims at the Jasenovac concentration camp remains unresolved, with estimates varying widely from around 80,000 to 700,000. Given the systematic destruction of records and the passing of time, the exact numbers will likely never be known. Yet, this lack of precision shouldn’t divert us from the human tragedy that these numbers represent.

More crucial than a definitive figure are the individual stories of those who suffered and perished at Jasenovac – their names, their faces, their lives. Each victim was someone’s son or daughter, brother or sister, father or mother. They had dreams and ambitions, joys and sorrows. Each one was a unique individual, not merely a number in a vast and tragic tally.

Remembering the victims of Jasenovac, and indeed any atrocity, is a task that goes beyond mere statistics. It requires a commitment to remember each person, to restore their dignity and individuality, to rescue them from oblivion. It demands a dedication to telling their stories, to ensuring that their lives, as well as their deaths, are acknowledged and commemorated. In this way, they cease to be anonymous victims and become human beings again, reminding us of the profound human cost of hatred, intolerance, and violence.

Memorial Sites: The Legacy of Jasenovac Concentration Camp Today

Today, the memories of those who suffered and perished are preserved through two memorial areas: Donja Gradina Memorial Area and Jasenovac Memorial Area. These memorial sites stand not only as commemorations of the past but also as warnings for the future, guarding the memory of those who suffered in an effort to ensure such atrocities never repeat.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!