Explore ‘A Brief History of Native American People’: Uncover the rich heritage, diverse cultures, and significant contributions of the indigenous peoples of North America.

“The Emergence of Complex Societies: The Ancestral Puebloans and Mississippian Cultures”

The fabric of North American pre-Columbian history is a rich tapestry of interwoven cultures, each with its own vibrant strands of socio-economic complexity and religious fervor. Paramount among these are the Ancestral Puebloans of the Southwest and the Mississippians of the Midwest, societies whose advanced practices in agriculture, architecture, and trade irrefutably challenge the persistent misconceptions of a simplistic or primitive indigenous past.

The Ancestral Puebloans, ancestors of the modern Hopi, Zuni, and Rio Grande Pueblo peoples, first rose to prominence around AD 500 in the arid but resource-rich landscapes of the Four Corners region. Advancements in maize cultivation stimulated a shift towards sedentism, which subsequently led to a surge in architectural innovation and social stratification. Spectacular apartment-like structures, hewn from the native sandstone, housed growing populations in communities like Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. These multi-story marvels bear witness to the advanced engineering and collective cooperation that was instrumental in their creation.

Parallel to the Puebloan culture in the Southwest, the Mississippian civilization emerged around AD 800 along the fertile floodplains of the Mississippi River. This culture is most notable for its vast ceremonial complexes, punctuated by earthen platform mounds and intricate plaza layouts, reminiscent of the urban planning seen in other contemporaneous civilizations. Cahokia, the most prominent of these centers, was a bustling metropolis, whose population at its peak rivaled that of medieval London.

The Mississippian society also saw the rise of a complex chiefdom structure, with elite classes exercising control over trade networks and the redistribution of surplus crops. The widespread adoption of shell-tempered pottery, distinctive copper artistry, and a writing system based on engraved symbols or “glyphs,” further underscored the sophisticated nature of the Mississippian culture.

A crucial aspect of both the Ancestral Puebloan and Mississippian societies was their cosmology. They deeply revered the natural world, and their societies were imbued with a profound sense of the sacred. Archaeological evidence attests to the centrality of celestial observations in their ceremonial practices, with architectural alignments correlating with solar and lunar events, underscoring their refined understanding of astronomy.

Indeed, the histories of the Ancestral Puebloans and the Mississippians reveal a world of remarkable complexity and dynamism, far removed from the stereotypes of primitive indigenous life. Their achievements in agriculture, architecture, social organization, and cosmology constituted a crucial part of the human narrative, deeply rooted in the North American soil long before European contact. Understanding their societies’ nuances and intricacies is key to an inclusive and informed interpretation of Native American history.

“Migration, Diversification, and Power Dynamics: Transition to a Complex Era”

After the zenith of the Ancestral Puebloan and Mississippian cultures, a pivotal shift occurred in the tapestry of Native American history. The period was marked by large-scale migrations, linguistic diversification, the growth of complex agricultural practices, and an intricate network of tribal alliances and conflicts. This chapter chronicles this transformative era, providing essential context to the dynamic pre-Columbian landscape.

Migrations in this epoch were often prompted by environmental changes, population pressures, and conflicts. As groups moved, they carried with them their languages, cultures, and technologies, leading to significant diversification. Linguistic evidence indicates the proliferation of major language families, such as Algonquian in the Northeast and Midwest, Athabaskan in the Southwest and Northwest, and Siouan, Iroquoian, and Muskogean in the Southeast.

Agricultural practices also developed significantly during this era, notably the cultivation of the ‘Three Sisters’: maize (corn), beans, and squash. This agricultural triad, highly complementary in nature, improved soil fertility and provided a balanced diet, leading to population growth and the development of permanent villages. Societies based on these practices, like the Iroquoian and Muskogean tribes in the Southeast, established sophisticated sociopolitical structures with significant agricultural surpluses.

Simultaneously, the complex dynamics of power among the tribes began to take shape. In the Great Plains, tribes like the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, and Comanche, initially engaged in a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, started forming alliances and engaging in warfare, driven by control over hunting grounds and trade routes. In the Northeast, the Iroquoian-speaking tribes, including the Mohawk and Seneca, united in the powerful Iroquois Confederacy, creating a formidable force that dominated the region for centuries.

The far-reaching implications of these developments cannot be overstated. The period marked a transition from largely isolated, sedentary societies to a mosaic of interconnected, complex societies marked by social hierarchy, political structures, and economic trade networks. The societies that Europeans encountered at the dawn of the 15th century were far from primitive; they were the product of centuries of evolution, adaptation, and innovation. They were societies that had, against many challenges, carved out a vibrant existence on the diverse North American continent.

“European Contact and Its Impact: The Colombian Exchange and Early Colonization”

The entwined destiny of the Native American peoples and the Europeans commenced with the momentous voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492. This transatlantic journey marked the beginning of the Colombian Exchange, an epoch of transformative biological and cultural exchanges that reverberated across continents and centuries.

The Europeans, bristling with ambitions of conquest and religious conversion, came bearing a trove of alien flora, fauna, and, most devastatingly, a host of diseases. The susceptibility of the indigenous populations to these new diseases such as smallpox, measles, and influenza, resulted in catastrophic loss of life, with some estimates suggesting a population reduction of up to 90%. This demographic calamity had profound implications for the socio-political structures of the Native American societies, leading to disruptions and collapses that made them vulnerable to European incursions.

Early colonization efforts often rested on a paradoxical mixture of violence and cooperation. In the Northeast, the Iroquoian and Algonquian peoples grappled with the arrival of English and Dutch colonists. Relationships were initially characterized by trade, particularly in furs and pelts, but as European hunger for land escalated, so did conflict.

The Spanish colonization of the Southwest and Florida followed a more direct path of conquest, exemplified by the entradas. Armed expeditions, driven by lust for gold and the zealous mission to convert ‘heathens’, resulted in brutal subjugation of tribes like the Apalachee and Pueblo. Yet, Native Americans often resisted, as exemplified in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, which led to a temporary expulsion of the Spanish from New Mexico.

In the Southeast, the so-called ‘Three-Sister’ farming societies – the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole – faced similar challenges from English and Spanish colonizers. Complex alliances, coerced conversions, slave trading, and territorial disputes marked their early encounters.

However, amidst the tumult of conquest and colonization, there was cultural exchange. The Native Americans adopted and adapted European goods, from iron tools to firearms, weaving them into their material culture. Similarly, European cuisine was transformed by the introduction of New World crops like corn, potatoes, and tomatoes.

Despite the imbalances, Native Americans were not passive victims. They negotiated, adapted, and resisted in a rapidly changing world. The history of early European contact and colonization is as much a story of indigenous resilience and agency as it is a tale of European expansion. It is a turbulent chapter of intertwining destinies, forever shaping the contours of what would become modern North America.

“The Struggle for Sovereignty: Native American Resistance and Treaties”

The collision of European colonizers with Native American societies marked a seismic shift in the course of history, triggering the fierce struggle for sovereignty that would define the succeeding centuries. This era was defined by Native American resistance against European encroachment, interspersed with a complex tapestry of treaties often marred by betrayal and bloodshed.

As the colonies grew, indigenous tribes found themselves increasingly marginalized, their territories shrinking under relentless European expansion. However, resistance was resolute. Many tribes did not passively accept the loss of their lands and cultures. From Metacom’s War, or King Philip’s War, in New England in the late 17th century, to the Pan-Indian resistance led by Tecumseh in the early 19th century, to the victorious Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, indigenous societies fought valiantly against settler colonialism.

Yet, military resistance was not the only means by which Native American societies sought to maintain their autonomy. Throughout this tumultuous era, a staggering number of treaties were negotiated between tribal leaders and colonial or U.S. representatives. These treaties were intended to guarantee the rights of Native American tribes, promising peace and the protection of their lands.

Notable among these were the Treaties of Hopewell in the late 18th century, the first treaties between the U.S. and Native American tribes, and the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, which recognized the Black Hills as sacred to the Lakota Sioux. However, many of these treaties were either ignored or violated by the U.S., leading to further conflicts and discontent.

Despite these immense challenges, indigenous societies persistently struggled for sovereignty, a struggle that continues to this day. Through both war and diplomacy, Native Americans sought to maintain their lands, their rights, and their way of life. This chapter of Native American history bears testimony to their resilience, adaptability, and an unyielding spirit that refused to be silenced or erased. It sets the stage for a deeper exploration into the contemporary struggles of Native American societies, a subject that remains vital in the continuing quest for justice and recognition.

“Assimilation and Resilience: The Indian Boarding Schools and Cultural Survival”

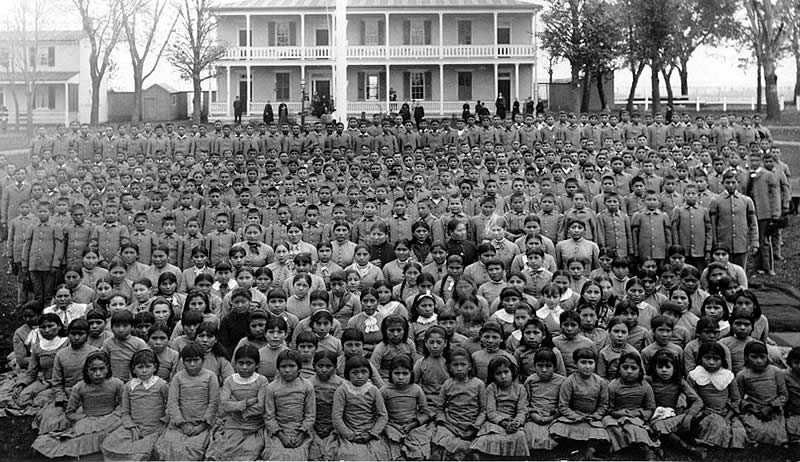

The late 19th and 20th centuries ushered in a new phase of U.S. government policy towards Native Americans: forced assimilation. At the heart of this devastating chapter were the Indian Boarding Schools, institutions designed to ‘civilize’ and assimilate Native American children into Euro-American society. Yet, amid this dark era, the flame of cultural survival flickered persistently, illuminating stories of resilience and resistance.

The implementation of the boarding school system was largely driven by the motto, “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” coined by Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. These schools, scattered across the country, were mandated to erase all traces of indigenous identity. Native American children were separated from their families, forbidden from speaking their languages, and forced to adopt Euro-American customs, names, and religions.

However, these institutions, which propagated cultural genocide, became paradoxical epicenters of cultural preservation and resilience. Far from their homes, many Native American children clung to their identities with tenacity, covertly practicing their languages and traditions, and forming new intertribal relationships.

Over time, the horrors of the boarding schools became more widely recognized, leading to the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978, which sought to limit the removal of Native American children from their families and cultures. Yet, the scars of this period run deep, and communities continue to grapple with the multi-generational trauma inflicted by these schools.

This period of forced assimilation also incited a broader cultural reawakening. The 20th century saw a powerful resurgence of indigenous activism and cultural pride. From the Red Power Movement and the occupation of Alcatraz Island, to the establishment of tribal colleges and preservation of indigenous languages, Native American communities have fought to reclaim and revitalize their cultures.

“Assimilation and Resilience” is a testament to the enduring strength of Native American cultures. Despite enduring the systematic erasure of their identities, these communities have displayed remarkable resilience, reclaiming their heritage, healing from past traumas, and building a future that honors their ancestors while shaping their distinct path forward.

“Activism and Recognition in the 20th Century: The American Indian Movement and Beyond”

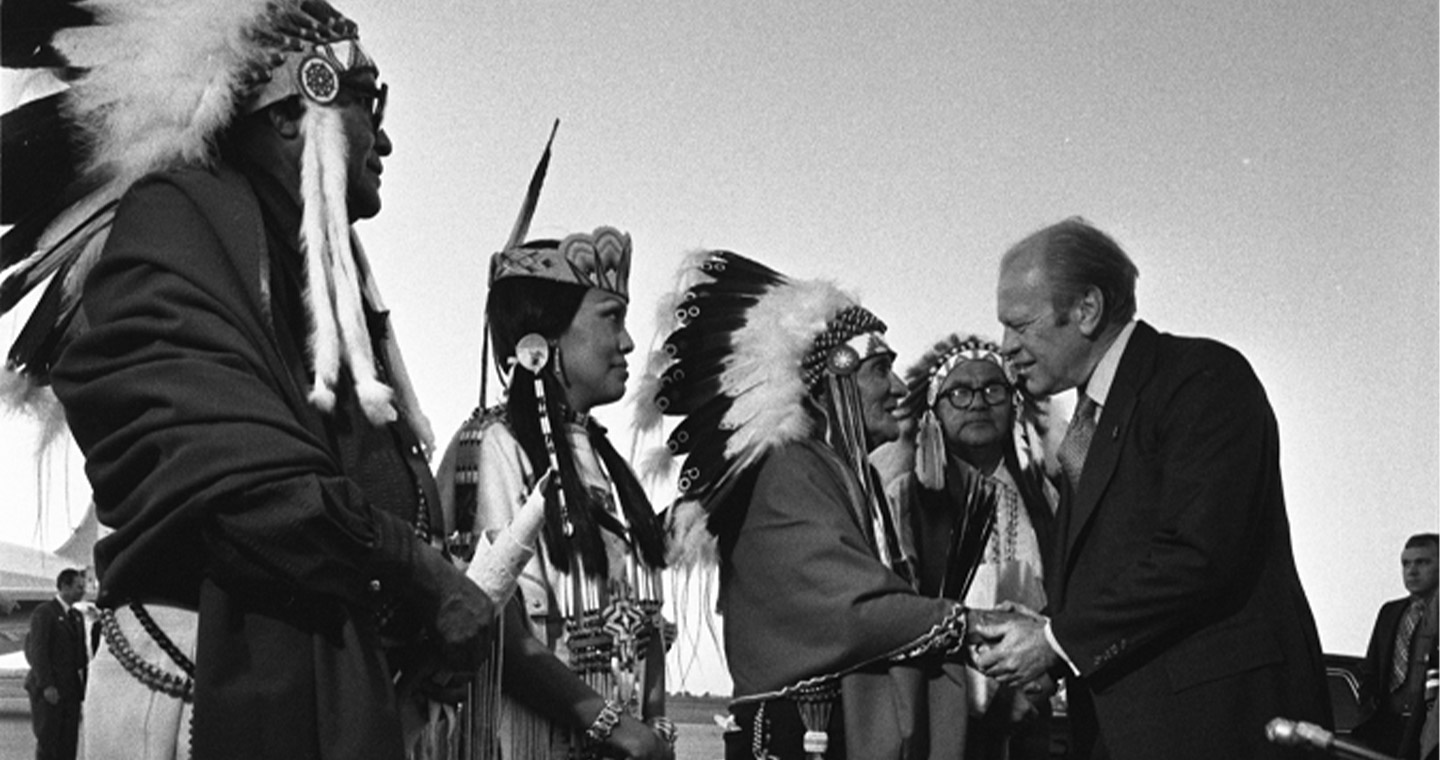

The 20th century heralded a new era of Native American activism, a period characterized by organized resistance and the fight for recognition. Central to this narrative is the American Indian Movement (AIM), which mobilized Native American communities across the nation to fight for their rights, sovereignty, and cultural preservation.

Founded in 1968 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, AIM emerged as a beacon of pan-Indian unity. It sought to confront and correct the systemic injustices faced by Native Americans, from police brutality and discrimination to the erosion of treaty rights. AIM’s efforts culminated in several high-profile demonstrations that marked turning points in Native American activism.

One such event was the occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969. Under the banner of “Indians of All Tribes,” activists occupied Alcatraz for 19 months, demanding that the abandoned federal property be returned to Native peoples as a cultural center. While the occupation ended without meeting its specific demands, it brought national attention to the struggles of Native American communities, amplifying their voices like never before.

Another significant event was the 1973 standoff at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. AIM members, alongside Oglala Lakota residents, staged a 71-day occupation to protest against corrupt tribal leadership and U.S. government violations of treaties. This event further pushed Native American issues into the national consciousness, highlighting the urgent need for policy reforms.

Beyond AIM, the 20th century also witnessed significant legal milestones, such as the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990. These pieces of legislation represented steps towards greater tribal sovereignty and the protection of indigenous cultural heritage.

The era of AIM and subsequent activism irrevocably shifted the narrative surrounding Native American communities, from one of erasure to one of persistent resistance and survival. Native American activism in the 20th century and beyond underlines an ongoing fight for recognition, cultural preservation, and the rectification of historical injustices, thereby shaping a narrative of resilience, identity, and self-determination in the face of centuries of adversity.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!