The Library of Alexandria remains one of the most enchanting topics in ancient history. Often caught between the realms of history and myth, the Library’s narrative especially resonates when we discuss the lost knowledge of antiquity. At the heart of these discussions is the alleged destruction of this storied institution. What proportion of our knowledge is based on myth, and how much is grounded in historical fact? In the text that follows, we will jointly explore these intriguing questions, delving into the legendary tales and established truths surrounding the Library of Alexandria.

Founding of Alexandria

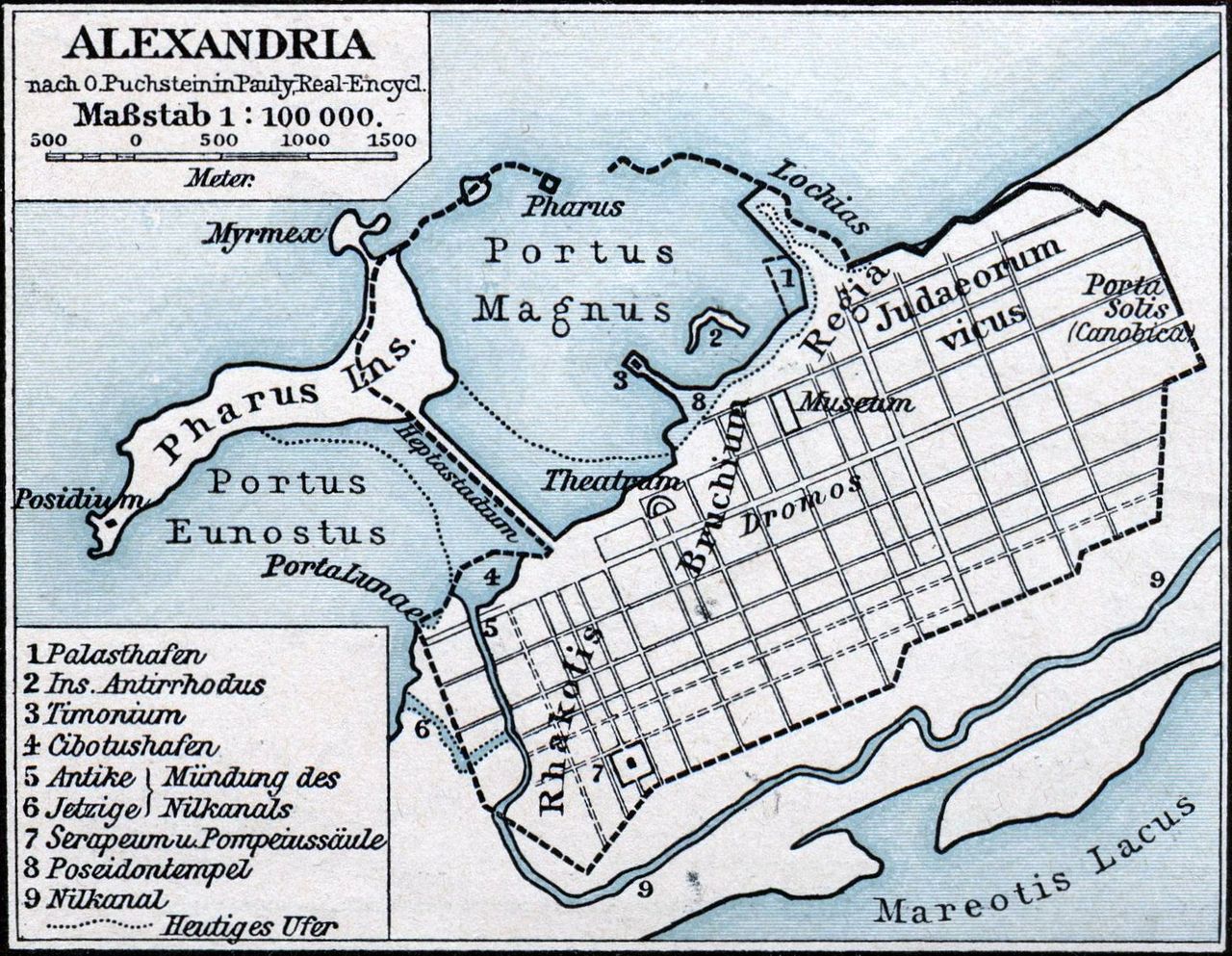

The city of Alexandria, historically known as al-Iskandariyya in Arabic, was conceived by none other than Alexander the Great. Founded in 331 B.C.E., Alexandria was strategically placed on the Mediterranean Sea coast at the northwest edge of the Nile Delta. This location not only provided a prime maritime gateway but also situated the city on a narrow strip of land between the sea and Lake Mariut, historically known as Mareotis.

The site was chosen over the small village of Rakhotis, which was previously home to fishermen and pirates. Alexander commissioned the Greek architect Dinocrates of Rhodes to design and build the new city, leaving it under the governance of his trusted general, Ptolemy, who would later be known as Ptolemy I. Alexandria was destined to become a key economic and cultural hub, as well as the final resting place of its illustrious founder.

As Alexandria took shape, it rapidly evolved into a vital economic center, usurping the commercial might of the ancient city of Tyre following its decline due to Alexander’s conquests. The city’s prominence only grew, soon outstripping even Carthage, once the heart of civilization in the Mediterranean. Under the rule of the Ptolemaic dynasty during the Hellenistic period, Alexandria reached its zenith, becoming the bustling commercial nexus of the Mediterranean. It was a melting pot of cultures and commerce, where ships from Europe, the Arab lands, and India converged, contributing to its status as a preeminent port in the Mediterranean Basin. The cosmopolitan populace comprised mainly Jews, Greeks, and Egyptians, each adding their unique cultural imprint to the burgeoning metropolis.

Founding of the Library of Alexandria

The Library of Alexandria, an intellectual marvel of the ancient world, was established around 283 B.C.E. under the Ptolemaic dynasty. Formed by a synodos of 30 to 50 scholars, the library featured multiple wings, shelves, covered walkways, lecture theaters, and even a botanical garden. A scholar-librarian, appointed as the royal tutor by the king, directed its construction.

By the third century B.C.E., the library boasted an impressive collection of approximately 400,000 mixed scrolls and 90,000 single scrolls. Initially, these scrolls were made of papyrus, a material that Alexandria had monopolized for a time. However, as a strategic move to curb the growth of rival libraries, the king later restricted the export of papyrus, prompting a shift to parchment for scroll making. These precious scrolls were carefully stored in linen or leather jackets, preserving the knowledge contained within.

One of the primary historical sources for the library’s founding is the Letter of Aristeas, which provides a vivid narrative of the library’s early days. According to this document, Demetrius of Phaleron, tasked with overseeing the king’s library, was given abundant resources to gather all possible books worldwide. He aimed to expand the library’s collection from over 200,000 books to 500,000.

During a discussion, Demetrius expressed the need to include Jewish laws in the library, which required translation from their unique script. Upon learning this, the king facilitated the acquisition by writing to the High Priest of the Jews, thereby endorsing the library’s mission to embrace a universal scope of knowledge. This anecdote underscores the library’s ambitious goal to serve as a comprehensive repository of the world’s knowledge, reflecting the Ptolemaic rulers’ dedication to culture and education.

Library of Alexandria – Center of Ancient Knowledge, Culture, and Literacy

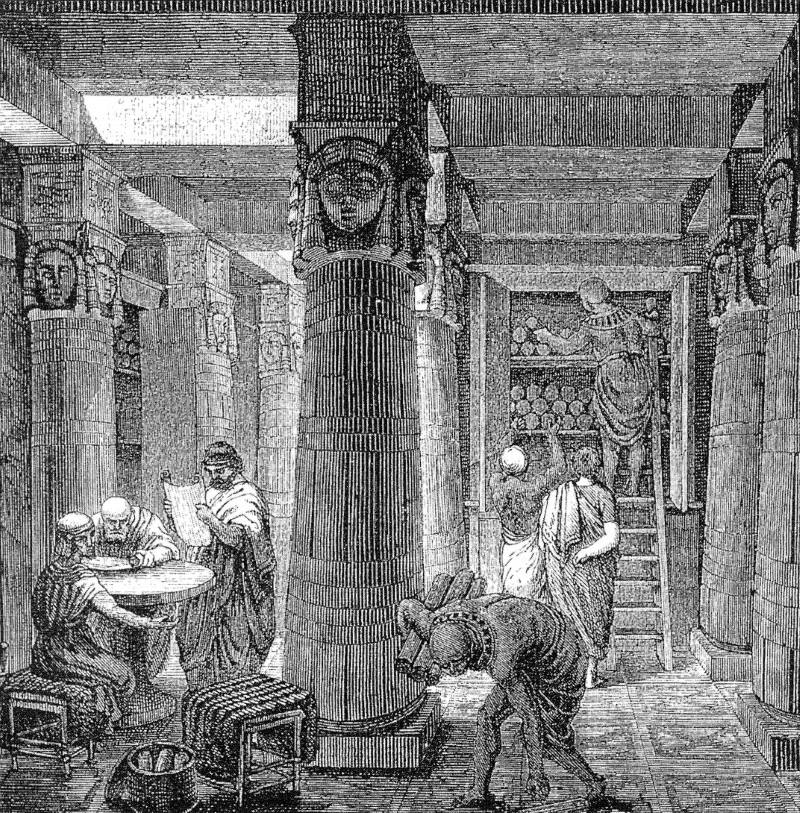

The Library of Alexandria was not just a repository of books, but a dynamic center of intellectual activity and translation that bridged diverse cultures and languages. Within its walls, translators, known as charakitai or “scribblers,” played a crucial role. They diligently translated and transcribed manuscripts from Greece, Babylon, India, and other parts of the known world, preserving and extending the reach of their wisdom. This massive undertaking by the charakitai was instrumental in cementing Alexandria’s position as a pivotal hub of knowledge in ancient civilization. The kings of Alexandria were ambitious in their quest to amass a comprehensive collection of global knowledge, reflecting their dedication to cultural and intellectual expansion.

This institution also served as the nurturing ground for some of the most illustrious minds of the ancient world. Euclid, the renowned mathematician, developed his influential work “Elements” around 300 B.C.E. in Alexandria, setting the foundations of modern geometry. Alongside him, Apollonius of Perga expanded the horizons of mathematical thought with his work “Conics,” which redefined geometrical concepts. The literary culture of Alexandria also thrived with figures like Apollonius of Rhodes, who penned the epic “Argonautica,” blending adventure with the artistry of words to create what many consider the first true romance.

Alexandria was also home to Archimedes of Syracuse, who made foundational contributions to physics and mathematics here, including his observations on the rise and fall of the Nile and the invention of the Archimedean screw. Furthermore, Eratosthenes, another librarian of Alexandria, made groundbreaking strides in geography and mathematics, accurately calculating the Earth’s circumference and theorizing about the interconnectedness of the oceans. Together, these scholars and their monumental works underscored Alexandria’s unparalleled role in shaping the intellectual contours of the ancient world.

The Decline of the Library of Alexandria

The fate of the Library of Alexandria is shrouded in controversy and mystery, with numerous accounts of its partial or complete destruction over the centuries. One notable episode occurred during the conflict between Julius Caesar and Ptolemy XIII, who allied with Cleopatra, for control of Alexandria in 48/7 BCE. Ancient sources, including Seneca the Younger and Plutarch, provide conflicting reports about the extent of the damage.

Plutarch suggests that the library was destroyed when Caesar set fire to his ships to block the enemy, inadvertently causing a fire that spread throughout the city. However, Dio Cassius indicates that it was primarily the warehouses, which stored books and grain, that were affected, not necessarily the main library itself. The exact number of books lost, if any, during this conflict remains uncertain, with figures ranging widely from 40,000 to 400,000 scrolls.

Further compounding the library’s tragic history is the eventual destruction associated with later Roman and Christian dominance. By the time of Emperor Aurelian in 272 AD, Alexandria faced severe civic strife that led to significant architectural and cultural losses, including parts of the library housed in the Brucheion district. The final blow came during the Christianization of the empire, notably in 391 AD when Theophilus, the Christian patriarch of Alexandria, sanctioned by Emperor Theodosius I, initiated the destruction of pagan temples, including the Serapeum which housed part of the library’s collection. This act symbolized a shift from the classical world of learning to a predominately Christian and religious worldview, further diminishing the library’s role as a center of secular knowledge.

The ultimate fate of the library blends historical events with legend, notably the debated claim of an Arab conquest supposedly completing the destruction of any remaining books—a narrative that remains more symbolic than substantiated by historical evidence.

Was Ancient Knowledge Lost in the Library of Alexandria?

The Library of Alexandria is often depicted as the pinnacle of ancient knowledge and culture, a beacon of scholarship in the classical world. However, it was not an isolated phenomenon. Throughout the Mediterranean, numerous other libraries existed, each serving as a hub for the exchange and preservation of knowledge. One of the primary competitors was the library of Pergamum in Asia Minor. Founded around 200 B.C.E. by King Eumenes II or Attalus I, this library became a formidable rival to Alexandria. The competition was so intense that the Egyptians banned the export of papyrus, inadvertently prompting the Pergamenes to innovate with parchment, which became a crucial medium for book production.

In addition to Pergamum, other significant libraries flourished across the Mediterranean, such as those in Rhodes, Cos, Pella, and Antioch. These institutions collectively ensured that knowledge was not confined to any single repository but was rather a shared resource across different cultures and empires. The Roman Empire later inherited this tradition, seamlessly linking Greek scholarly practices with the emerging Roman intellectual culture.

Rome itself boasted numerous libraries by the first century C.E., influenced heavily by Greek scholarship. Prominent figures like Cicero and Plutarch documented the extensive efforts made to acquire books and the elaborate systems established for their lending, copying, and organization. Libraries in Rome were often founded as public displays of wealth and culture, with several dedicated to Emperors like Vespasian, Trajan, and Marcus Aurelius.

The Library of Celsus in Ephesus, Turkey, was a grand Roman building that housed around 12,000 scrolls. Built as a tomb for a Roman official, it became one of the largest libraries of the ancient world, though the interior was destroyed by fire in the 3rd century AD. (Source: Wikipedia)

By the time of Constantine the Great, the tradition of collecting books had become well established, with Constantine transferring thousands of volumes from Rome to start a new collection in Constantinople, which eventually amassed 120,000 books. These Roman and later Byzantine libraries were the direct descendants of the Alexandrian tradition, preserving and perpetuating the ancient wisdom well into the medieval period. Thus, while the Library of Alexandria was indeed a magnificent treasury of knowledge, it was part of a broader network of libraries that safeguarded and disseminated scholarly works throughout antiquity. This network ensured that even though individual libraries might suffer losses, the collective repository of human understanding remained robust and accessible across different regions and epochs.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!