On December 29, 1890, the incident at Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota unfolded, an event that has since ignited a complex debate among scholars and historians. Labeling it varies significantly, with some asserting it was a massacre, while others argue it was a battle, showcasing the enduring schism in perspectives regarding this pivotal moment in American history. As a historian with a broad interest in reading and without specialized expertise in Native American history, I intend to contribute my analysis to this discourse. From my vantage point, what commenced as a confrontation evolved tragically into a massacre, a transformation that merits a detailed exploration to fully understand the nuances of this historical episode.

The Prelude to Tragedy

The path to the calamity at Wounded Knee Creek was paved with a series of escalating tensions and policies that deeply affected the Native American populations on the Great Plains. In the years leading up to 1890, the United States government aggressively pursued a policy of westward expansion, systematically displacing Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands to make way for settlers. This era, marked by broken treaties and forced relocations, culminated in the reservation system, designed to confine Native American tribes to defined areas, drastically altering their traditional way of life. The discovery of gold in the Black Hills, a region sacred to the Lakota, further exacerbated these tensions, leading to a series of conflicts and betrayals that deeply entrenched animosity between Native American tribes and the U.S. government.

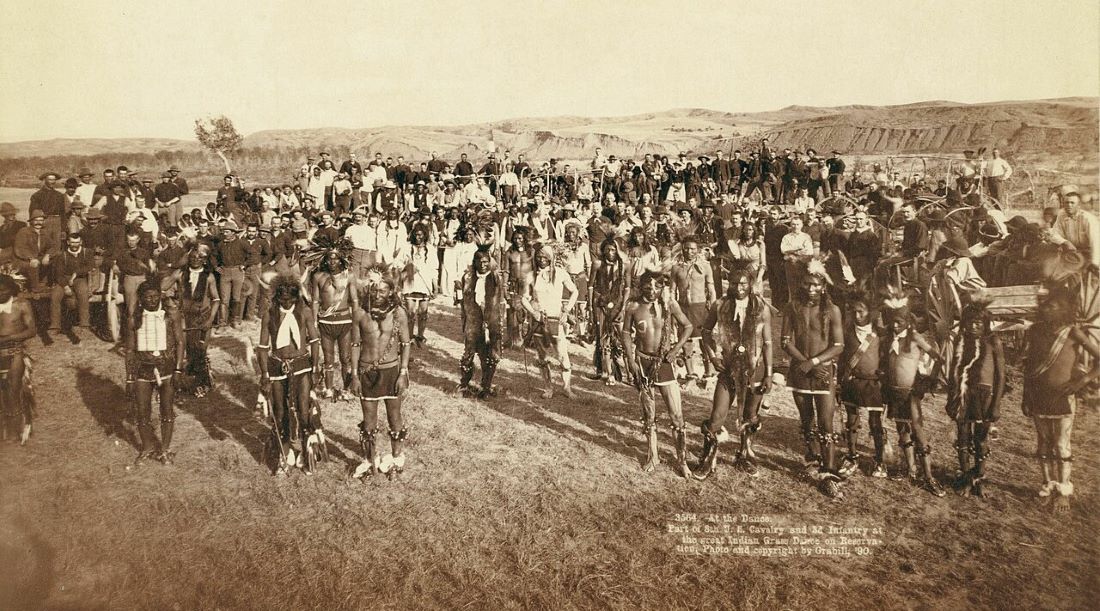

Amidst this backdrop of despair and displacement, the Ghost Dance movement emerged as a powerful symbol of hope and renewal for Native Americans. Prophetized by the Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka, the Ghost Dance was a religious revival that promised the restoration of the Native American way of life, the return of the buffalo, and the reunion with ancestors. To the beleaguered tribes on the reservations, it represented a peaceful form of resistance, a way to reclaim their culture and dignity. However, to the U.S. authorities, the growing popularity of the Ghost Dance among the Lakota and other tribes was perceived as a threat, a potential precursor to armed rebellion. Misunderstandings and fear of this spiritual movement set the stage for the tragic events that were to unfold at Wounded Knee, as military intervention was deemed necessary to quell what was seen as a rising tide of Indigenous insurgency.

Disarmament and Chaos at Wounded Knee

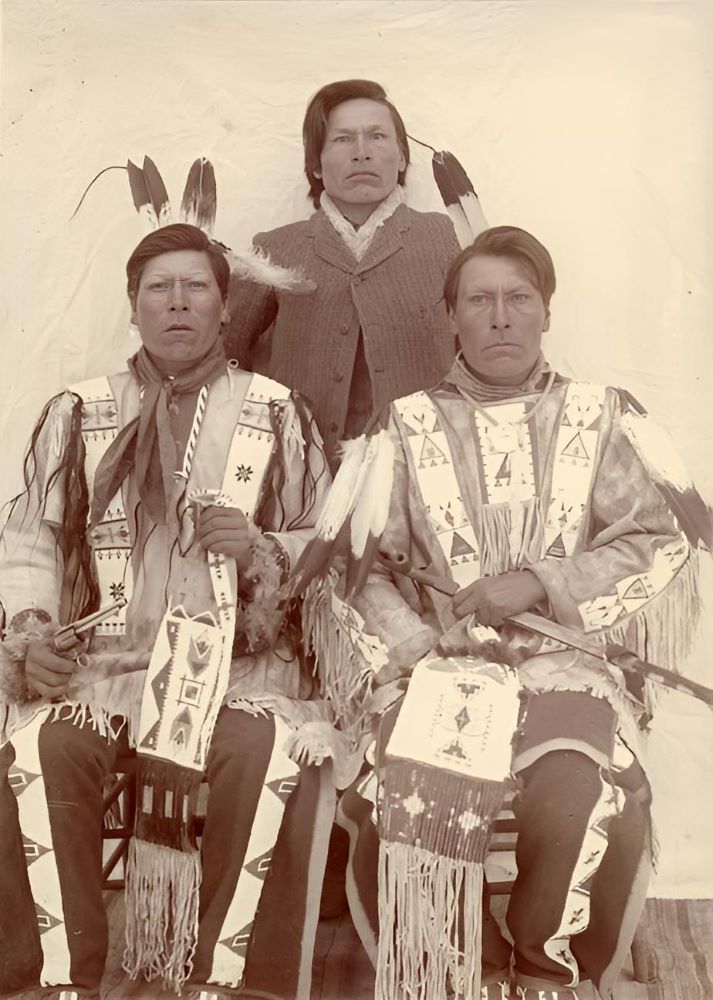

After being summoned to the Pine Ridge Agency, Spotted Elk of the Miniconjou Lakota and his 350 followers, on December 28, 1890, embarked on the arduous journey towards the agency. Their progress was halted by a detachment of the 7th Cavalry under Major Samuel M. Whitside southwest of Porcupine Butte. John Shangreau, a scout and interpreter of half-Lakota descent, cautioned the troopers against an immediate disarmament of the Lakota, warning it could lead to violence. Heeding this advice only temporarily, the troopers escorted the Native Americans to Wounded Knee Creek, instructing them to camp there. By evening, Colonel James W. Forsyth arrived with additional troops, swelling the military presence to 500 against the 350 Lakota, comprising 230 men and 120 women and children. The U.S. forces encircled Spotted Elk’s camp, ominously positioning four Hotchkiss M1875 mountain guns, setting the stage for a tragic confrontation.

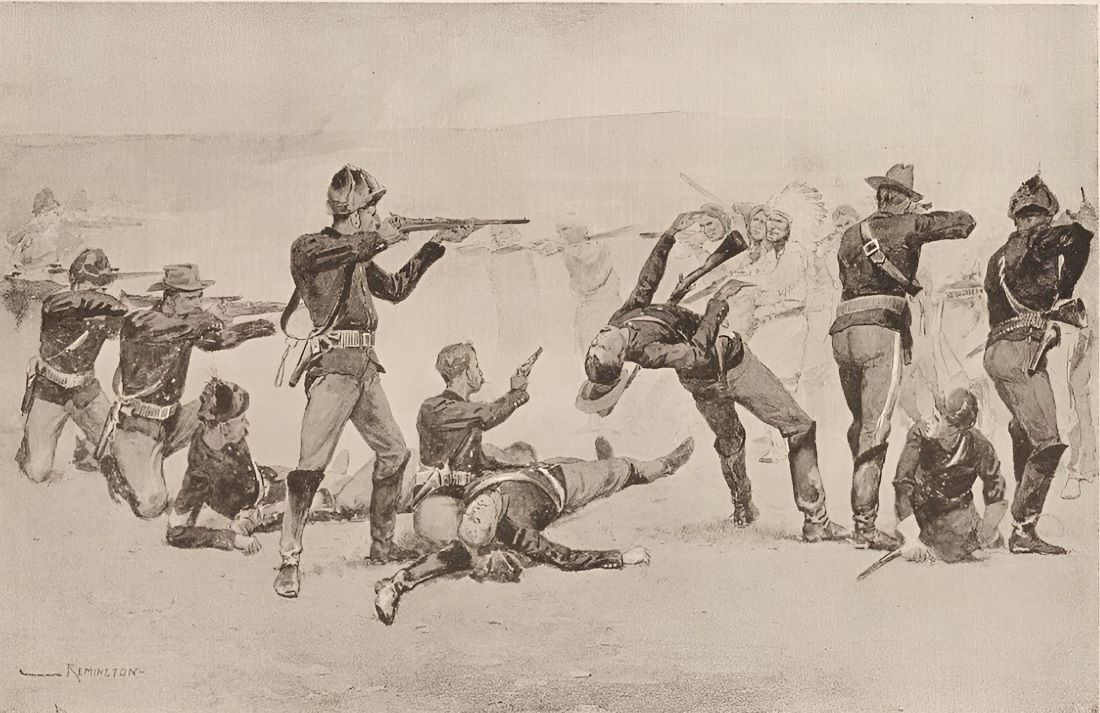

The tension escalated the following morning during the disarmament process. An atmosphere of mistrust and fear pervaded, exacerbated by the language barrier and the soldiers’ insistence on confiscating every weapon. The situation reached a boiling point with Black Coyote, a deaf Lakota warrior who, misunderstanding the situation due to his impairment, refused to surrender his newly purchased Winchester rifle. Arguing that he had paid a lot for it, he resisted relinquishing it. Amidst the confusion and a scuffle that ensued, the rifle discharged, whether by accident or force, remains unclear. This single gunshot catalyzed the chaos that followed. The soldiers, interpreting the discharge as an act of aggression, opened fire, leading to a frenzied and indiscriminate slaughter that shifted swiftly from a perceived battle to a harrowing massacre, leaving scores of Lakota men, women, and children dead or dying in the snow.

Analyzing the Event

Understanding the tragic events of Wounded Knee requires a nuanced examination of several key factors leading up to the confrontation. The initial question centers on the aggressive disarmament strategy applied to a non-combative group of Sioux, raising doubts about its necessity and the appropriateness of the 7th Cavalry’s involvement. Given the unit’s historical defeat at Little Big Horn and its well-documented animosity toward the Sioux and Lakota tribes, the decision to engage them in this context suggests a predisposition towards conflict rather than peacekeeping.

The preemptive surrender of weapons by the Lakota—over 30 guns from an assembly that could scarcely muster 120 potential fighters—indicates a lack of hostile intent, challenging the narrative that a battle was imminent. This act of compliance, disarming a quarter of their capable warriors, strongly counters the notion of a premeditated conflict on their part. The subsequent actions of the 7th Cavalry, seemingly in search of a pretext to initiate aggression, spotlight the tragic inevitability of the ensuing violence.

The aftermath of the encounter, where the definition of a battle blurs into the horror of a massacre, reveals the extent of the tragedy. The relentless pursuit and execution of women and children, far removed from the battlefield, by U.S. troops betray a shocking brutality.

The most vivid description of the event is provided by an eyewitness account from Hugh McGinnis of the 7th Cavalry.

General Nelson A. Miles who visited the scene of carnage, following a three-day blizzard, estimated that around 300 snow shrouded forms were strewn over the countryside. He also discovered to his horror that helpless children and women with babies in their arms had been chased as far as two miles [3 km] from the original scene of encounter and cut down without mercy by the troopers. … Judging by the slaughter on the battlefield it was suggested that the soldiers simply went berserk. For who could explain such a merciless disregard for life? … As I see it the battle was more or less a matter of spontaneous combustion, sparked by mutual distrust.

It Was Indeed a Massacre

The deliberate actions taken by the U.S. military, coupled with the eyewitness accounts describing the merciless execution of non-combatants, underscore the brutality of the event. Given the comprehensive examination of the facts and testimonies, it becomes clear that the Wounded Knee incident was a massacre, an egregious act of violence that marks one of the most tragic moments in the history of the United States’ relations with Native American peoples.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!