Richard the Lionheart and Saladin (or Salah ad-Din) are two of the most prominent figures from the time of the Crusades. They were adversaries during the Third Crusade (1189-1192), with Richard leading the Christian forces and Saladin leading the Muslim forces.

Here’s a brief overview of each:

Richard the Lionheart (Richard I of England, 1157-1199):

- Born in Oxford, England, Richard was the third son of King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine.

- Although he was King of England, he spent little time in the country, being more invested in his lands in France and his role in the Crusades.

- Known for his martial prowess, Richard earned the nickname “Lionheart” due to his courageous and fierce nature in battle.

- His reputation as a military leader was solidified during the Third Crusade where he won significant battles, such as the Battle of Arsuf.

- However, despite his efforts, he failed to recapture Jerusalem from Saladin, which was the main objective of the Third Crusade.

- On his way back to England after the Crusade, Richard was captured and held for ransom by Leopold V, Duke of Austria. After his release, he spent the remainder of his life in Western Europe, where he died after being wounded during a minor siege.

Saladin (Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, 1137-1193):

- Born into a Kurdish family in Tikrit (now in modern-day Iraq), Saladin rose to power in the tumultuous world of 12th-century Middle East politics.

- He united the various Muslim factions and established the Ayyubid dynasty, which ruled over large parts of the Middle East.

- His most notable accomplishment was the recapture of Jerusalem from the Crusaders in 1187, which precipitated the Third Crusade.

- Saladin was known not just for his military skills, but also for his chivalry, justice, and generosity. His interactions with Richard during the Third Crusade became the stuff of legend, with both leaders often showing mutual respect.

- After years of conflict, Saladin and Richard agreed to the Treaty of Ramla in 1192, which allowed Christian pilgrims access to Jerusalem but kept the city under Muslim control.

- Saladin died in Damascus in 1193, not long after the end of the Third Crusade.

Richard and Saladin on the Battlefield

The sun-scorched landscapes of the Holy Land bore witness to a legendary conflict during the Third Crusade. Richard the Lionheart, the gallant king of England, and Saladin, the unifying force of the Muslim world, would face each other across battle lines drawn in the sands of the Middle East. Their encounters on the battlefield would resonate through the annals of history, illustrating a unique blend of martial prowess, strategy, and chivalrous respect.

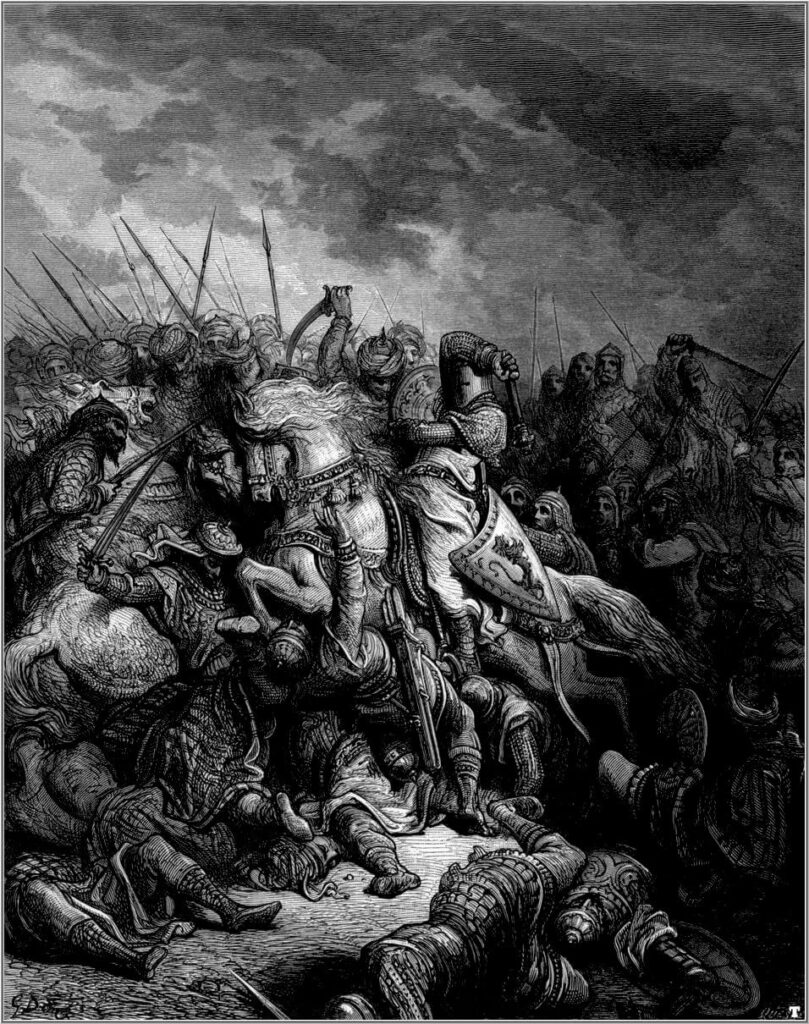

The Battle of Arsuf in 1191 was one such intense encounter. Richard’s forces, moving to capture the port city of Jaffa, faced relentless harassment from Saladin’s troops. Saladin, adopting a strategy of continuous skirmishes, hoped to weaken and demoralize the Crusader army. However, Richard displayed exceptional patience, maintaining the formation of his troops and waiting for the opportune moment. When that moment arrived, Richard ordered a massive cavalry charge that broke through Saladin’s lines, leading to a decisive victory for the Crusaders.

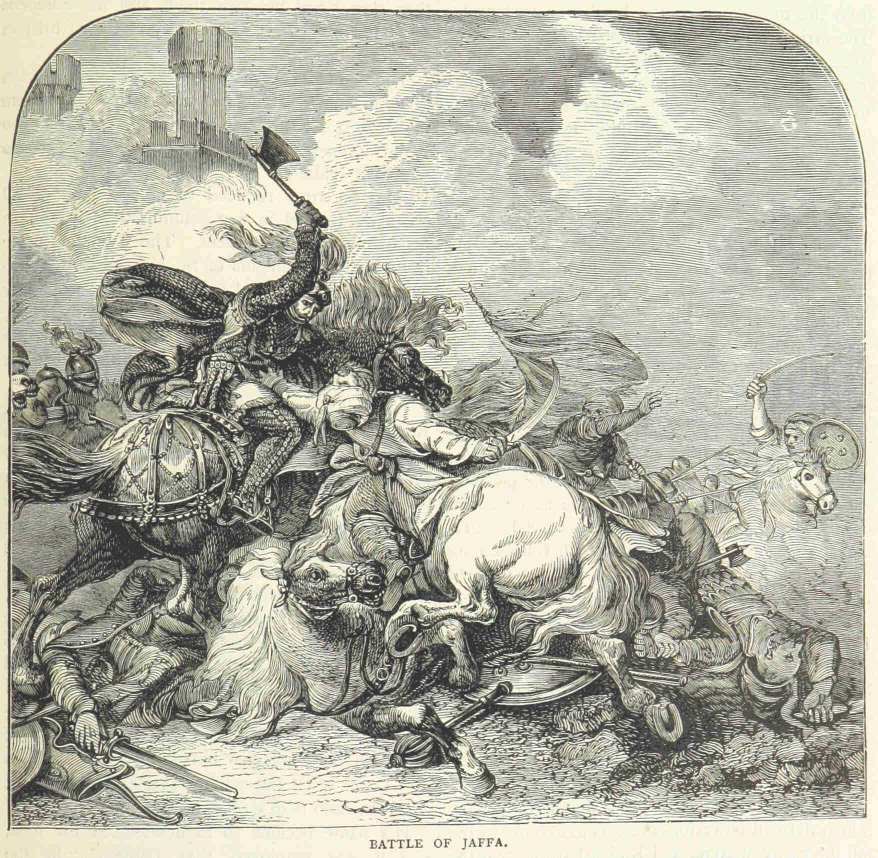

Yet, it wasn’t just their tactical genius that made these encounters memorable. Their personalities and leadership styles often shone through. Richard, with his fearless frontline presence, inspired his men to push forward, even in the face of daunting odds. His audacity was evident at the Battle of Jaffa in 1192, where, despite being heavily outnumbered, Richard’s direct involvement in the combat bolstered the morale of his troops, compelling Saladin’s forces to withdraw.

Saladin, on the other hand, was a master of psychological warfare. His strategy often revolved around wearing down the enemy, using swift hit-and-run tactics, a hallmark of his light cavalry. But it was also his sense of honor and chivalry that set him apart. Stories abound of Saladin sending ice and fruits to Richard when he was sick, and Richard, in return, sending his own physician to attend to Saladin’s ailing brother.

Their encounters were not just about the clash of swords and shields but also the interplay of mutual respect and admiration. In one anecdotal encounter, when Richard’s horse was killed beneath him, Saladin is said to have sent him a fresh steed, signaling respect for a worthy adversary.

The final act of their legendary encounters culminated in the Treaty of Ramla. While the two never achieved their ultimate goals—Richard could not reclaim Jerusalem, and Saladin couldn’t decisively defeat the Crusaders—the treaty showcased their pragmatic sides. Recognizing the futility of endless bloodshed, they agreed to terms that allowed Christian pilgrims access to the Holy City, while it remained under Muslim control.

In the tapestry of history, the encounters between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin stand out not just as a testament to their military acumen but also as a reminder that even in war, respect and understanding can find a place.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!