Palman of Letinberch stands as one of Emperor Dušan’s most significant mercenaries, yet historical accounts have often erroneously referred to him as Palman Bracht. This text aims to delve deeper into the life and company of this enigmatic figure, bringing forth historical data to shed light on his true story. We will explore his contributions and impact while dispelling prevalent myths, providing a clearer understanding of his role in the tumultuous era of Emperor Dušan’s reign.

Palman of Letinberch: The Knight and The Diplomat

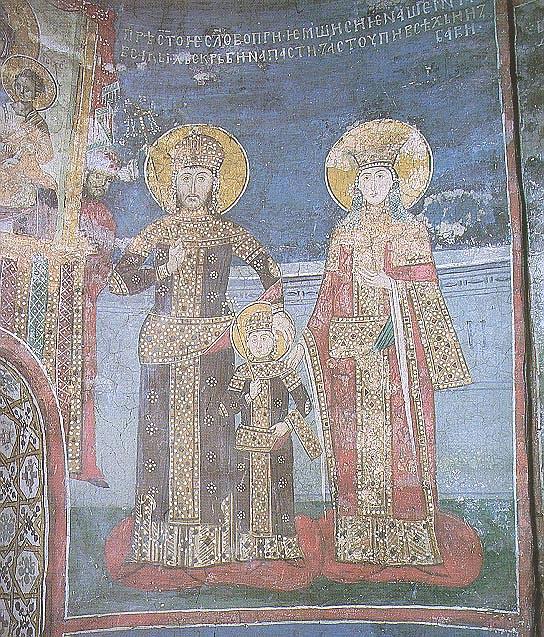

Palman of Letinberch emerged on the historical stage around October 1333 when he was in Dubrovnik to collect equipment for an unnamed mercenary in the service of the Nemanjić rulers. By this time, Palman had already established himself within the inner circle of the Serbian ruler, Stefan Dušan. Emperor Dušan, known as Stefan Dušan, was the Serbian King (1331–1346) and later Emperor (1346–1355). He is noted for his significant territorial expansions and the codification of laws, known as Dušan’s Code. Palman’s appearance coincides with the period of the most remarkable territorial expansion of the Nemanjić state, reflecting the tumultuous times of the 14th-century Balkans.

Palman’s role was not limited to military endeavors; he also demonstrated diplomatic skills, particularly in negotiations between Stefan Dušan and various European powers like the Habsburgs and the Papal Curia. His first recorded historical appearance in Dubrovnik, where he was involved in trade activities, suggests a broader scope of influence and responsibilities. Palman’s career, spanning approximately three decades (ca. 1333–1363), reveals him as not just a mercenary commander but also a resourceful and skillful diplomat. His multifaceted contributions during this tumultuous time underscore his integral role in the expansion and diplomacy of the Nemanjić state under Emperor Stefan Dušan.

Dušan’s Guard

Emperor Stefan Dušan’s formidable army was significantly bolstered by the Teutonic Company, an elite mercenary group led by Palman of Letinberch, numbering around 300 skilled warriors. These troops were not merely foot soldiers but also served as a potent cavalry force, adaptable to various combat situations. Historical accounts detail Palman’s procurement of extensive and varied military equipment in Dubrovnik around 1333. This arsenal included heavy armor such as cuirass breastplates, and helmets with chain undercaps, along with leg and thigh protection, signifying their role as heavily armored cavalry units. In addition to this, they were equipped with tunics, horse covers, and saddles, further underlining their versatility and importance in battle.

The Teutonic Company’s strategic importance and their varied combat roles exemplify the military might and tactical diversity of Dušan’s forces. While the Teutonic Company was a primary focus, it’s worth noting that the Catalan Company, though subordinate to the Empress, also contributed to the diverse military strength of Dušan’s reign. Together, these mercenary groups played crucial roles in the territorial expansions and military triumphs of Emperor Stefan Dušan’s era.

Palman’s Final Campaign: The Siege of Klis

In the autumn of 1355, during a precarious period in Serbian-Hungarian relations, Palman of Letinberch found himself during a significant military operation. Stefan Dušan’s half-sister, Jelena, sought her brother’s aid against increasing Hungarian pressure to defend her territories in Dalmatia after the death of her husband, Mladen III Šubić. Despite a peace treaty with King Louis of Hungary, Dušan opted for a limited military engagement to support Jelena, dispatching two contingents to safeguard her key strongholds of Klis and Skradin.

Palman, leading members of his company, was tasked with the defense of Klis. He arrived there in mid-November 1355 and, alongside Mersota who led the local forces, took charge of the citadel’s defense. Soon, they found themselves besieged by the forces of Nicholas (Miklós) Bánffy, the Ban of Croatia. Despite the besiegers capturing parts of the town and its defenses, the citadel under Palman’s command remained impregnable for a time. Amidst these tensions, negotiations between Venice and Stefan Dušan occurred, aiming to prevent the fortresses from falling to the Hungarians. However, the sudden death of Stefan Dušan in December 1355 dramatically altered the situation.

The news of Dušan’s death reverberated through the region by early January 1356, severely impacting the morale of the defenders. Skradin was soon relinquished to the Venetians. Palman likely maintained control over Klis slightly longer but was eventually compelled to surrender by March 1356 when the fortress was reported to be in Hungarian hands. Palman survived the ordeal but faded from the historical records soon after. He was last mentioned in 1363 when a Dubrovnik merchant left him a sum of money, suggesting he might have had connections or even resided in the city following the events at Klis. Alternatively, he may have returned to Serbian lands to serve Dušan’s son, Tsar Uroš. As the Nemanjić dynasty’s power waned, Palman of Letinberch silently exited the historical stage, leaving behind a legacy intertwined with the rise and fall of one of the most significant empires in the Balkans.

Dušan’s Guard: The Myth of the Towering Warriors

The myth of Emperor Stefan Dušan’s elite guard is a compelling narrative woven into the fabric of Serbian folklore. According to popular legend, Dušan commanded a guard of 300 soldiers, each allegedly over 2 meters tall, with Dušan himself towering above them all, save for his standard-bearer, who was the tallest. This imposing unit is said to have been so formidable that their mere appearance before a city would compel it to surrender without a fight.

Furthermore, the legend extends to feats of rapid military conquest, such as the claim that this elite guard was instrumental in quelling a rebellion in Epirus in just 28 days. The narrative paints them as an invincible force, a symbol of Dušan’s power and the might of the Serbian Empire at its zenith.

However, despite its captivating details, there is a significant lack of historical evidence to substantiate these claims. No contemporary records or accounts confirm the existence of such a uniquely-tall and overpowering guard. While Stefan Dušan’s reign is well-documented for its military achievements and territorial expansions, the specific tale of a 2-meter-tall elite guard seems to be more a product of myth and national pride than historical fact. It’s a compelling story that has captured the imagination, but it remains just that—a story, with no solid foundation in the historical records of the time.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!