The Kingdom of Yugoslavia, previously known as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes until October 1929, spanned between the 41st and 47th degree of northern geographical longitude. With an area of 247,542 km², it housed 12,055,715 inhabitants as per the 1921 census, thereby categorizing it amongst the large European nations. It encapsulated the central and western part of the Balkan Peninsula, extended towards the Pannonian Plain, touched the Alps, and spread to the Adriatic Sea. Its convoluted coastline, brimming with archipelagos and ports, connected it with the rest of the world.

The region where the Kingdom of Yugoslavia originated exhibited diverse cultural, historical, and economic development, which prompted varying attitudes of the populace towards the state, territory, military, and governance. Norway was the first to acknowledge the new state on January 26, 1919, followed by the USA, Greece, and Switzerland. Italy, due to border disputes, only recognized it in November 1920.

According to the first constitution, adopted in the National Assembly on June 28, 1921, the Kingdom was declared a constitutional, parliamentary, and hereditary monarchy, with Serbo-Croatian-Slovenian as the official language. The Karadjordjevic dynasty held the reins of the Kingdom, with the young and energetic Regent Alexander, who became the King following his father, King Peter I’s demise, on August 16, 1921. The constitution defined the King as the central figure, representing the state in all relations with other countries, serving as the supreme military commander, and holding the authority to declare war and peace.

From its inception, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia proved to be an extremely politically unstable state. Divisions that arose during World War I, over the manner of unification and the form of the state, only deepened after the establishment of a common state. While the so-called state-building parties, the People’s Radical Party, and the Democratic Party, advocated for monarchy and unitarism, on the other hand, the most influential Croatian party, the Croatian Republican Peasant Party (which dropped Republican from its name in 1925 and became the Croatian Peasant Party), advocated for a republic and federalization of the state. However, no party was consistent in its intentions, which often led to unusual political combinations, and consequently, frequent changes in the government. By the outbreak of World War II, in just under 23 years, 39 governments had changed. Stjepan Radić, leader of the Croatian Peasant Party, which briefly joined the government of Nikola Pašić in 1925, was the most vocal in attempts to revise the constitution. Following “harsh words” in the national assembly on June 20, 1928, the leader of the People’s Radical Party, Puniša Račić, carried out an assassination on the delegates of the Croatian Peasant Party, killing Pavle Radić and Đuro Basariček, and mortally wounding Stjepan Radić (who later died from his injuries on August 8).

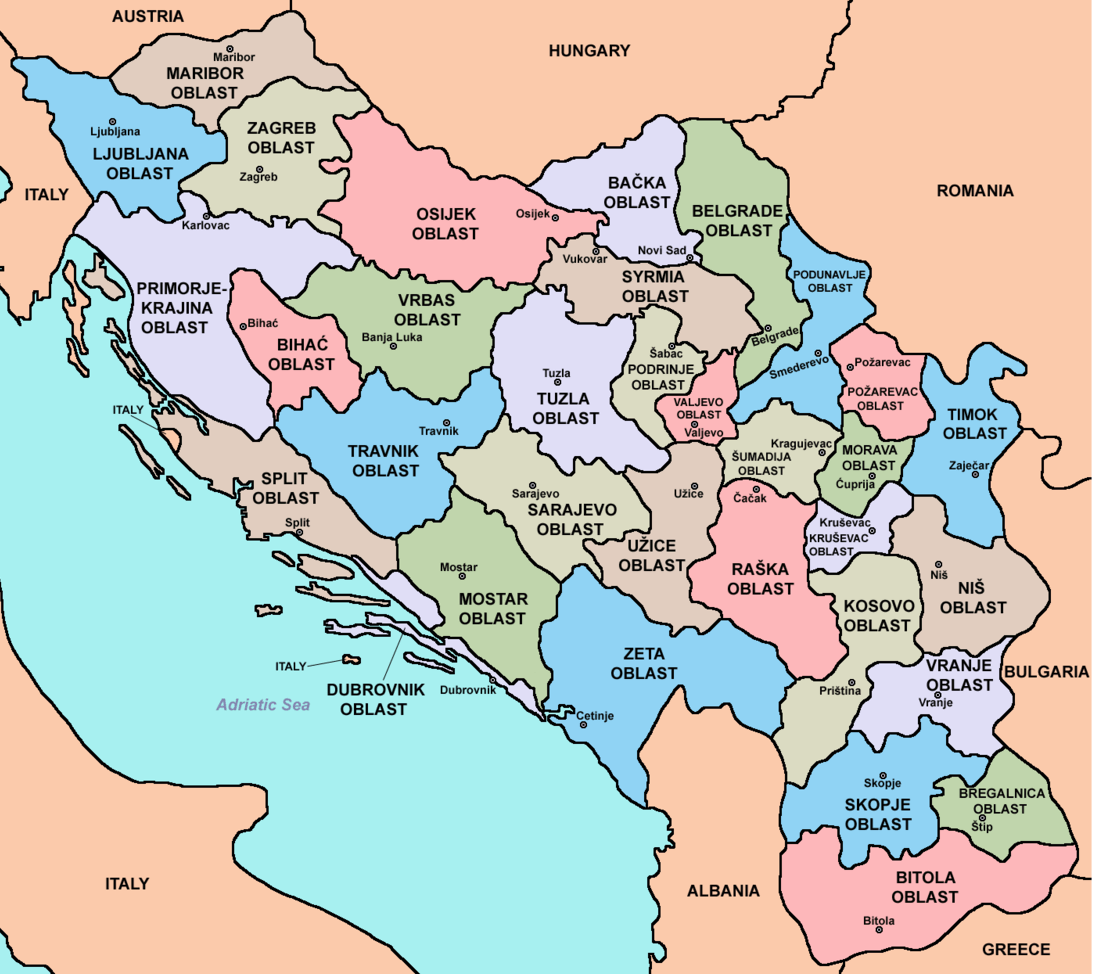

Following the assassination attempt, on January 6, 1929, King Alexander decided to abolish the constitution, dissolve the assembly, ban political activity, and establish personal dictatorship until the situation in the country is resolved and passions are cooled. Most political entities approved the king’s actions, considering his procedure justified and temporary. In October 1929, the king renamed the country to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and introduced a new administrative territorial division. The Kingdom was divided into nine banovinas (and the independent Administration of the City of Belgrade), which were named after rivers, following the French model, to avoid any mention of national identifiers. Displeased that the people’s assembly was not reinstated after the situation in the country had calmed down, representatives of political parties increasingly criticized the king’s regime. To appease the public, in September 1931, the king granted a new constitution, which was not a product of a constitutional assembly, but an act of the king’s will. The constitution itself was a mixture of the king’s personal rule with elements of parliamentarism. It was only after the assassination of King Alexander, on October 9, 1934, in Marseille, that full parliamentary system was restored.

The pressing political issue throughout the Kingdom of Yugoslavia’s existence was the formation of a Croatian federal unit. With the formation of the government led by Dragisa Cvetkovic and supported by Regent Paul Karadjordjevic, they began addressing the Croatian question in 1939. An agreement between Prime Minister Dragisa Cvetkovic and the Croatian Peasant Party leader Vlatko Macek resulted in the creation of the Banovina of Croatia on August 26, 1939, initiating the federalization of the Yugoslav state.

Following Austria’s annexation in 1938, Hitler and Fascist Italy began exerting increasing pressure on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and its government. With the defeat of France in 1940, Yugoslavia’s traditional ally, the new Yugoslav government began moving closer to the fascist nations. Regent Paul Karadjordjevic, initially inclined towards British politics, rejected their proposal for a joint Balkan front with Greece to thwart further German advances. Instead, he favored an agreement with Hitler to preserve Yugoslavia’s neutrality during the Second World War. This decision resulted in a public uprising and a military coup d’etat on March 27, 1941, overthrowing Regent Paul and installing 17-year-old Peter II as the new king.

However, these events caught the ire of Adolf Hitler, who then decided to crush Yugoslavia for their defiance. On April 6, 1941, the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria) invaded the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Despite their desperate resistance, the Yugoslav Army was overwhelmed, and the country was swiftly occupied and partitioned among the Axis powers.

The four-year occupation that ensued was a period of extreme brutality and bloodshed. Many local collaborators were formed, such as the Independent State of Croatia, which committed mass atrocities against Serbs, Jews, and Roma. Various resistance movements emerged, with the two most prominent ones being the Royalist Chetniks, loyal to the government-in-exile, and the communist-led Partisans, led by Josip Broz Tito.

After years of bitter and brutal warfare, the Partisans emerged victorious, pushing out the Axis powers and their collaborators and establishing a communist regime. King Peter II and the government-in-exile were barred from returning, marking the end of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

In 1945, the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia was established, later renamed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1963. This new state was a federation of six republics, namely, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia, effectively fulfilling the federalist aspirations from the pre-war period. This marked a new chapter in the history of the South Slavs, one under socialism and led by Tito, who would remain in power until his death in 1980.

Despite the end of the Kingdom, the legacy of the Yugoslav experiment lived on, with the memories, shared experiences, and unresolved issues continuing to shape the politics and societies of the successor states long after its dissolution.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!