Bacon’s Rebellion was the first rebellion in the American colonies. Taking place in 1676, this uprising was led by Nathaniel Bacon against the ruling governor, Sir William Berkeley. The rebellion arose from many issues, including grievances over Native American policies and economic struggles. Notably, Bacon’s Rebellion saw an unprecedented alliance between white and black indentured servants and enslaved people, unified in their opposition to the colonial elite. This cooperation highlighted the complex social dynamics of the time and foreshadowed the evolving nature of race relations in America.

Roots of Bacon’s Rebellion

Bacon’s Rebellion was sparked by a complex interplay of factors that went beyond mere Native American policies. High taxes imposed by the colonial government and low tobacco prices significantly burdened the settlers, many of whom were frontier planters struggling to make a living. Additionally, the system of indentured servitude created widespread discontent among both white and black laborers, who found common cause in their shared grievances against the ruling elite.

While the conflict with Native Americans was the immediate catalyst for the rebellion, the underlying issues were deeply rooted in economic and social injustices. Nathaniel Bacon, like many of his fellow frontier planters, believed that Governor Berkeley was failing to provide adequate protection from Native American attacks. Frustrated by Berkeley’s refusal to grant him a commission to lead a militia against the Native Americans, Bacon took matters into his own hands, rallying his followers to defend their lands and livelihoods.

The Course of Bacon’s Rebellion

Despite Governor Berkeley’s refusal to grant a commission, Nathaniel Bacon and his fellow planters perceived Native Americans as a more immediate threat than the Governor himself. Taking matters into their own hands, they launched attacks on nearby Native American communities. In response, Berkeley declared Bacon guilty of treason. The colonial legislature convened in June to address the escalating conflict, ultimately granting Bacon a commission to fight the Native Americans and enacting laws to reduce taxes and curb government abuses. However, Berkeley continued to withhold the commission, prompting Bacon and over 500 supporters to march into Jamestown.

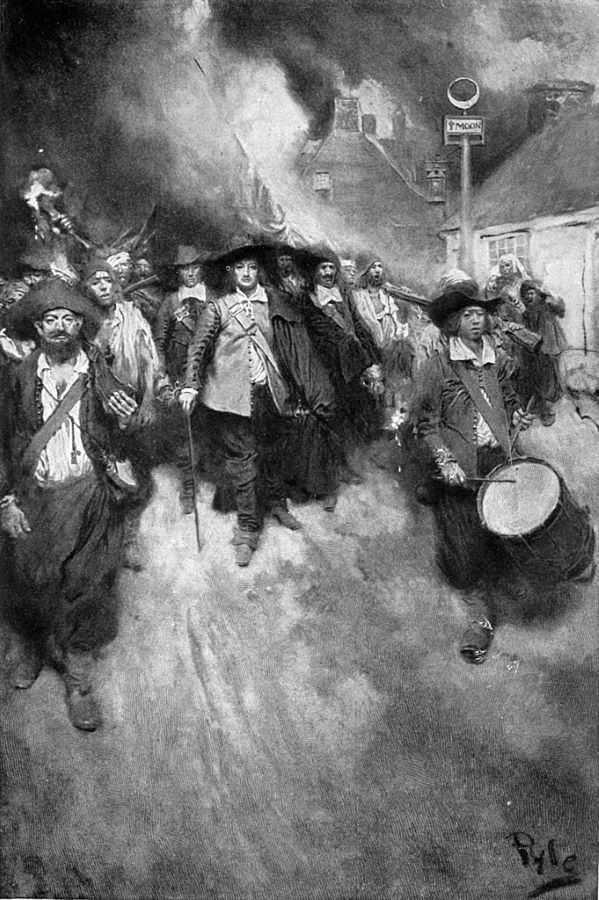

The conflict between Berkeley and Bacon intensified as both sought to amass support. Bacon promised land to any servant who would rise against their master, garnering significant backing from discontented settlers. By September 1676, Berkeley and his loyalists were forced to flee Jamestown, taking refuge on the eastern shore. To prevent their return, Bacon and his followers set Jamestown ablaze. However, Bacon’s sudden death in October 1676 (likely from dysentery) led to the rebellion’s swift collapse. Without their leader, the rebels lost momentum, allowing Berkeley to return and reassert control. In a harsh retribution, Berkeley hanged over 20 rebellion leaders and unleashed his forces to plunder Bacon’s remaining supporters.

Aftermath and Impact of Bacon’s Rebellion

The aftermath of Bacon’s Rebellion had profound implications for both the governance of Virginia and the institution of slavery. In London, the Crown authorities perceived the rebellion as a consequence of poor colonial administration. King Charles II, primarily concerned with the profitable cultivation of tobacco, saw the rebellion as a dangerous distraction from agricultural productivity. In response, he dispatched an army to restore order in Virginia and demanded the removal of Governor Berkeley, fearing that his unpopularity could incite further unrest. Berkeley was recalled to England in 1677, where he died shortly after.

The rebellion also accelerated the shift towards a more rigid system of racialized slavery. The temporary alliance between white and black laborers during the uprising alarmed the colonial elite, prompting them to create stricter laws to divide these groups and prevent future coalitions. By institutionalizing racial distinctions, the planters sought to solidify their control over the labor force and mitigate the risk of another rebellion. This shift laid the groundwork for the entrenchment of chattel slavery, shaping the socio-economic landscape of the American colonies for generations. Bacon’s Rebellion, though ultimately quelled, left a lasting legacy by highlighting the need for more responsive governance and sowing the seeds for the systemic racial divisions that would come to define colonial America.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!