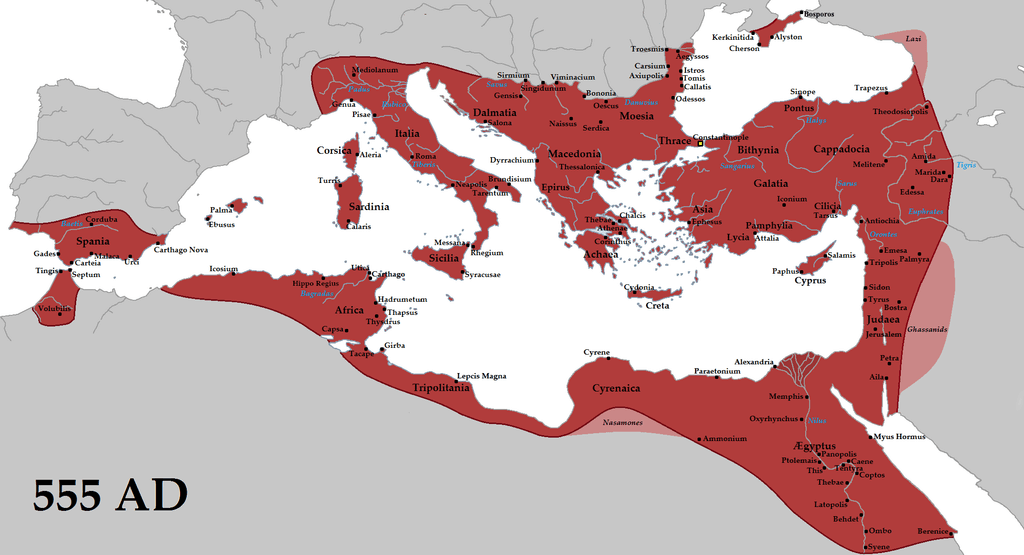

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was a continuation of the Roman Empire in its eastern provinces following the decline of the Western Roman Empire. Established in the 4th century AD, its capital was Constantinople, now known as Istanbul in modern-day Turkey. This resilient empire stood as a bastion of Christian civilization and Hellenistic traditions for over a millennium, stretching from the Balkans and Eastern Europe to the Mediterranean and parts of the Middle East. At its height, the Byzantine Empire was a beacon of culture, trade, and politics, lasting until the 15th century when it fell to the Ottoman Turks.

Let’s delve into seven captivating facts from this majestic realm.

Byzantium: The Heir to the Roman Legacy

The Byzantine Empire’s roots can be traced back to the grandeur of Ancient Rome. While the Western Roman Empire, with its iconic capital of Rome, often grabs most of the historical limelight, it was the Eastern Roman Empire – later to be known as the Byzantine Empire – that would carry on the torch of Roman civilization for an additional thousand years after the West’s collapse.

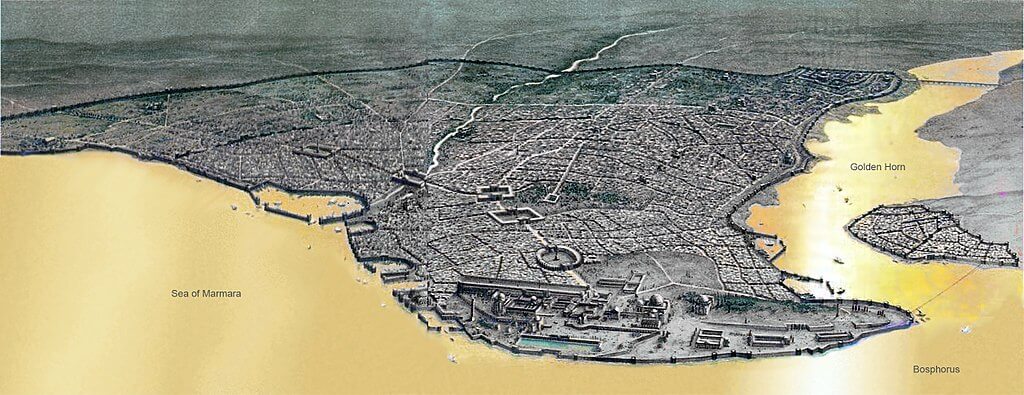

The term “Byzantine” originates from Byzantium, the city which Emperor Constantine I refounded and renamed as Constantinople in 330 AD, designating it the new capital of the Roman Empire. This shift from Rome to Constantinople signified a broader transition: while Latin remained the official language in the West, Greek became dominant in the East. The city, strategically situated between Europe and Asia and straddling the boundary of the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, became the heart of a new Roman realm. From its walls, emperors, and empresses would govern territories spanning from modern-day Italy in the West to Syria in the East. Under their watch, the essence of Roman law, architecture, art, and governance fused seamlessly with Hellenistic culture, Christian theology, and Eastern traditions to create a distinct and vibrant Byzantine identity. The Byzantine Empire, in essence, became the custodian of Roman heritage, ensuring its preservation and evolution in an ever-changing world.

Byzantium: The Bastion of Christianity

The evolution of the Byzantine Empire is intrinsically tied to the rise and spread of Christianity. It was in this crucible that key decisions and transformations regarding the Christian faith occurred. One of the watershed moments in the history of early Christianity was the issuing of the Edict of Milan in 313 AD by the Roman emperors Constantine I and Licinius. This proclamation effectively granted religious tolerance within the Roman Empire, allowing Christians to practice their faith without fear of persecution. This monumental shift in religious policy laid the foundation for Christianity’s pivotal role in the empire’s identity.

Nearly seven decades later, in 380 AD, Emperor Theodosius I issued the “Cunctos populos” decree, known today as the “Credo of Theodosius”. With this, Nicene Christianity (a branch of Christianity that adhered to the beliefs set out in the Nicene Creed) was declared the state religion of the Roman Empire. This solidified the church’s position at the center of Byzantine life. Following this, the Byzantine Empire played host to several ecumenical councils, most notably those in Nicaea, Constantinople, and Ephesus. These councils were instrumental in defining and shaping Christian theology, dogma, and practices that would influence not just the empire, but the entire Christian world.

The commitment of the Byzantines to Christianity was not just in declarations and councils but also in monumental architectural achievements. Among the most significant is the Hagia Sophia or “Holy Wisdom.” Commissioned by Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century, this architectural marvel in Constantinople was the world’s largest cathedral for nearly a thousand years. More than just a testament to Byzantine engineering and architectural prowess, the Hagia Sophia symbolized the empire’s deep-seated devotion to the Christian faith, standing as a beacon of Christian orthodoxy in the heart of the empire’s capital. It’s magnificent domes and intricate mosaics captured the spiritual aspirations and artistic achievements of a civilization at its zenith.

The Linguistic Evolution of Byzantium: From Latin to Greek

Language in the Byzantine Empire, as with all great civilizations, was not just a tool for communication but an embodiment of its culture, law, and administration. In the empire’s nascent stages, Latin was the dominant language. This was a continuation of the tradition from the Roman Empire, where Latin was the language of governance, law, and the military. The early Byzantine emperors, keen to connect themselves to the legacy of Rome, maintained Latin as the official language.

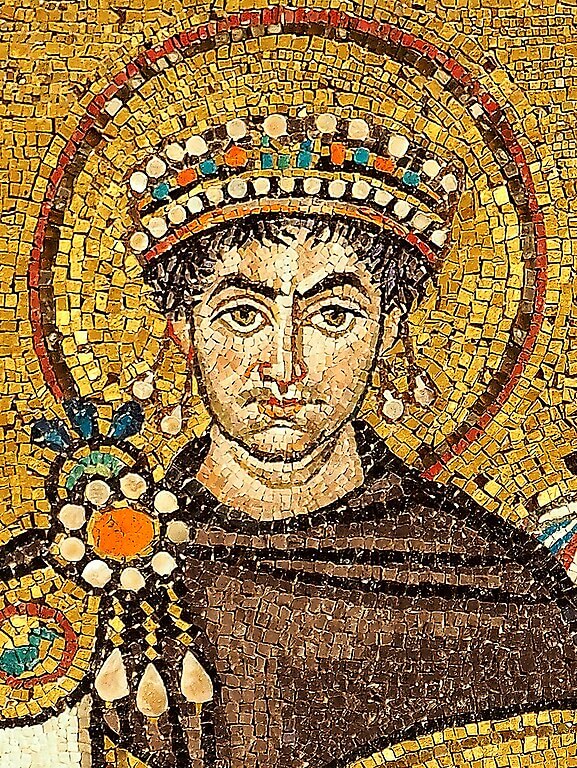

Emperor Justinian I, one of the most renowned Byzantine emperors, was a significant proponent of this Latin tradition. Under his reign in the 6th century, the vast and intricate body of Roman law was codified into what came to be known as the “Corpus Juris Civilis” or Justinian’s Code. This monumental legal compilation, written in Latin, was instrumental in preserving Roman legal principles and would go on to influence the development of legal systems in many parts of Europe.

However, as the centuries rolled on, the use of Latin began to wane, and Greek, which was widely spoken by the populace, started gaining prominence. By the 7th century, the shift towards Greek was palpable. This transition was not just a matter of practicality but also mirrored the empire’s evolving identity. As the Western Roman Empire and its Latin-speaking territories dwindled, the Byzantine Empire began to see itself more as a Greek Christian empire rather than a Latin one. By the time of the reign of Heraclius in the early 7th century, Greek had replaced Latin as the official language of the empire. This shift to Greek was not just limited to administration and daily life; it also permeated the realms of literature, theology, and art, further solidifying the unique and distinct identity of the Byzantine Empire.

The Artistic Legacy of Byzantium: An Enduring Influence

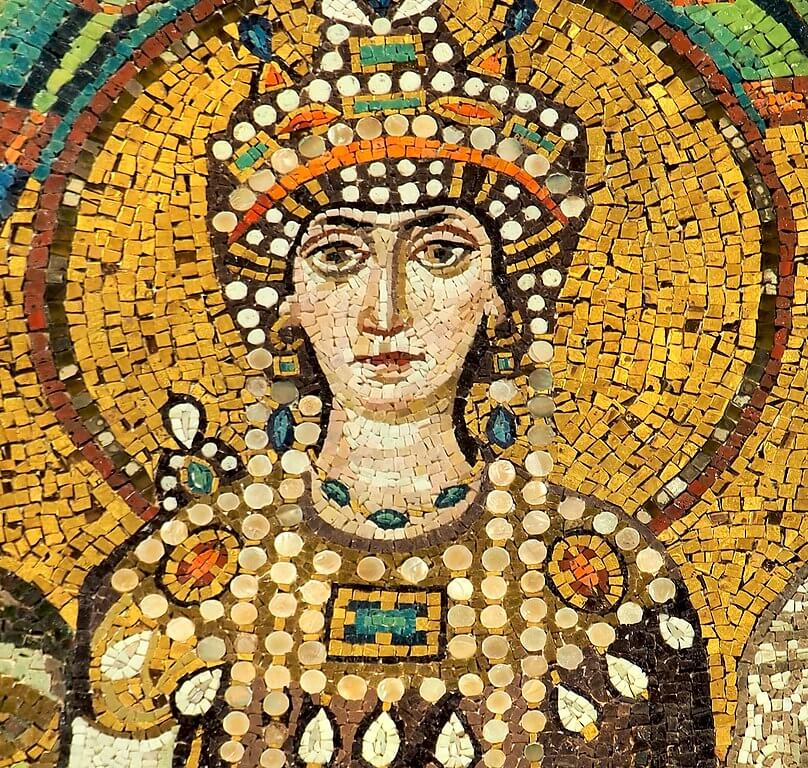

The Byzantine Empire, with its unique confluence of Roman, Hellenistic, and Christian traditions, gave birth to a distinctive art form that resonated deeply and left an indelible mark on subsequent generations. This art was characterized by its profound spiritual depth, its ornate decorative elements, and its majestic mosaics and frescoes that aimed not just to depict the worldly, but to transport the beholder to the divine.

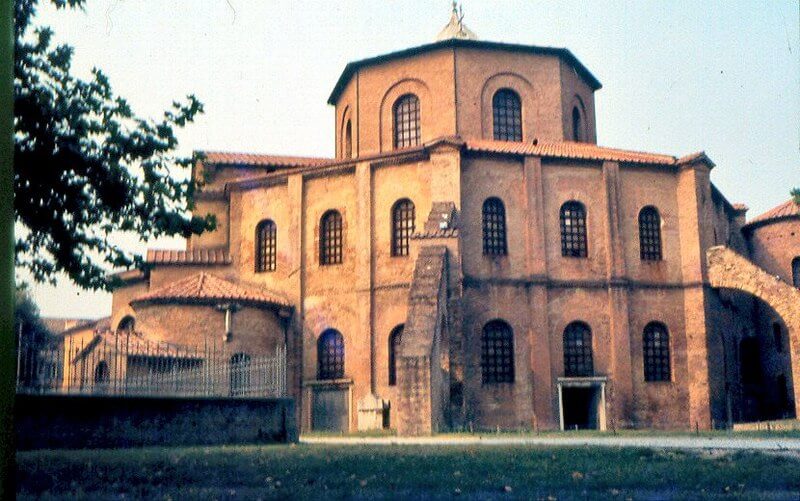

Architecturally, the Byzantines achieved unparalleled feats. The Hagia Sophia, already mentioned, stands out as the paragon of Byzantine architectural genius. But beyond this cathedral, Byzantine architecture showcased a proclivity for domes, which became emblematic of Orthodox Christian churches. The design allowed for large interior spaces bathed in ethereal light from the clerestory windows, a fitting representation of the divine light of God. The use of pendentives – a unique architectural feature that allowed for the placement of a dome over a square room – was a Byzantine innovation that would be utilized in structures across the globe.

The influence of Byzantine art, especially in architecture, is palpable among the Orthodox Christian nations of Eastern Europe. From the monasteries of Mount Athos in Greece to the churches of Serbia, Bulgaria, and Russia, the echoes of Byzantium are evident. One can witness the replication and evolution of the dome structures, the intricate iconography, and the richly decorated interiors that characterize the Byzantine design. These architectural traditions have survived the test of time, and many Orthodox Christian churches built today still carry the unmistakable touch of Byzantine inspiration.

But the legacy is not confined to bricks and mortar alone. Byzantine mosaics and icon paintings, with their gold backgrounds and ethereal depictions of saints and Biblical stories, became central to Orthodox religious practices. Even today, in many Eastern Orthodox traditions, these icons are venerated, and the art of icon painting is considered a sacred craft.

The imprint of Byzantine artistry extends beyond its immediate territories. Its motifs, designs, and techniques seeped into Western art, influencing the Renaissance and subsequent movements. Today, as one traverses the tapestry of cultures in Eastern Europe and the broader Mediterranean, the whispers of Byzantium, its art, its architecture, and its spirit, can still be felt, testifying to an empire that, while long gone, continues to live on in its enduring legacy.

The Byzantine Military Machine: Tagma, Themes, and the Rise of Feudalism

The Byzantine Empire, given its strategic location and the persistent threats it faced from both the East and the West, required a robust and flexible military system. Over its millennium-long history, this system evolved to address the changing dynamics of warfare and politics.

One of the earliest and most innovative systems adopted by the empire was the thematic system or “themes”. Introduced in the 7th century as a response to internal and external pressures, themes were essentially administrative and military districts. The empire was divided into these regions, each under the leadership of a strategos, a military governor. The thematic system served a dual purpose: it decentralized the military and administrative control, and it also tied the military to the land, ensuring that soldiers had a vested interest in the areas they protected. The soldiers were given plots of land in exchange for military service, creating a self-sustaining defense mechanism.

Parallel to the thematic troops, there were the ‘Tagmata’ or central armies stationed around the capital. These were elite units, ready to be deployed rapidly to any part of the empire that faced immediate threats. The famed Varangian Guard, composed largely of Norse and later Anglo-Saxon warriors, was one such elite tagmatic unit, serving as the personal bodyguards to the emperor.

As the empire faced increasing challenges, both financial and military, in the middle Byzantine period, there emerged the system of ‘pronoia’. This was a form of grant, where individuals, often soldiers or officers, were given rights to revenues from specific lands or towns, not the ownership of the land itself. This system can be seen as a precursor to feudalism. These ‘pronoiars’ would, in turn, provide military service to the empire. It was a way for the empire to maintain a sizable army without direct financial burdens.

However, over time, as these pronoia grants became hereditary, it led to the rise of a powerful landed aristocracy. This shift mirrored the broader trends in medieval Europe, where feudalism was taking root. These aristocratic families began to exert more influence and power, which at times challenged the authority of the emperor.

The Byzantine military apparatus, with its themes, tagmata, and pronoia, showcased the empire’s adaptability. It was a system that blended the traditional Roman legions with the medieval European feudal structures, ensuring that the empire remained a formidable force throughout its long history.

Women of Byzantium: Power, Influence, and Legacy

While the medieval world was often characterized by its patriarchal systems, the Byzantine Empire was notable for some exceptional women who defied conventions and left an indelible mark on history. These women navigated the complexities of Byzantine society, politics, and culture to influence the course of the empire’s history.

One of the most iconic figures in Byzantine history is Empress Theodora. Rising from humble origins and a checkered past, she became the co-ruler of the empire alongside her husband, Emperor Justinian I. Theodora was not just a ceremonial figure; she played an instrumental role in shaping the empire’s policies. During the Nika Riots, when the very existence of Justinian’s reign was under threat, it was Theodora’s resolve and counsel that emboldened the emperor to stand his ground and suppress the rebellion. She also championed the rights of women, advocating for policies that protected them from forced prostitution and granting them greater rights in divorce cases.

Another notable woman from Byzantine history is Anna Komnina, the daughter of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Anna was an accomplished scholar and historian. She penned “The Alexiad,” a monumental history detailing her father’s reign and the challenges of the First Crusade from the Byzantine perspective. In this work, Anna not only provides invaluable historical insights but also presents herself as a keen observer and critic of her times. While she was initially in line for the throne and had ambitions to rule, circumstances prevented her from achieving this goal. Yet, through her writings, Anna ensured her voice and perspective would resonate through the ages.

Apart from these prominent figures, women in Byzantine society played vital roles in various capacities. They were active participants in religious life, with many becoming nuns and some even attaining sainthood. Women were influential patrons of art and literature, and they were crucial in the domain of diplomacy, often forging key alliances through marriage.

While the Byzantine Empire was, in many ways, a product of its time with predefined gender roles, it also offered avenues for exceptional women to influence, lead, and inspire. The legacies of these women, from empresses to scholars, showcase the depth and diversity of female experiences in the Byzantine world.

Byzantium and the Crusades: The 1204 Catastrophe and Deepening Rifts

The Crusades, a series of religious wars sanctioned by the Latin Church, were initially undertaken with the primary aim of reclaiming the Holy Land from Muslim rule. However, as these campaigns progressed, their impact and implications extended far beyond the confines of the Levant, especially for the Byzantine Empire.

Byzantium’s relationship with the Crusaders was fraught from the outset. While the First Crusade in the late 11th century was prompted, in part, by Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos’s request for aid against the Seljuk Turks, the mutual mistrust and cultural misunderstandings between the Latin West and Byzantine East quickly became evident. The Crusaders and Byzantines often had different strategic objectives, and alliances were frequently made and broken.

This uneasy relationship reached its tragic climax during the Fourth Crusade. Instead of moving towards Jerusalem, the Crusaders, manipulated by Venetian interests and internal disputes, turned their attention to the greatest Christian city of the time: Constantinople. In 1204, the city faced a devastating sack at the hands of the Crusaders. Churches, monasteries, and palaces were plundered, and priceless artifacts were either destroyed or carried off to the West. The city’s inhabitants faced horrors, with countless killed or sold into slavery.

This event did more than just weaken the empire militarily and economically; it left a deep scar on the Byzantine psyche. The Fourth Crusade solidified the schism between Eastern and Western Christianity, arguably creating a divide more profound than the religious schism of 1054. While the Great Schism was primarily a theological and ecclesiastical dispute, the events of 1204 added layers of political, cultural, and personal animosity. Many in the East saw the sack of Constantinople as a betrayal by their fellow Christians, an act of treachery that was neither forgotten nor fully forgiven.

Though Byzantines would eventually reclaim Constantinople in 1261, the empire was a shadow of its former self, having lost significant territories and resources. More than just territorial losses, the events of the Fourth Crusade intensified the mistrust and antagonism between the Christian East and West, with ramifications that would echo for centuries to come.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!