What Happened to Yugoslavia?

Featured Image: General map of Yugoslavia 1945-1991.The story of Yugoslavia’s unraveling continues to perplex and fascinate, not only historians, but also ordinary observers. It was a country that, from an outside perspective, exhibited all the characteristics of a successful nation. And yet, it dissolved dramatically into a whirlwind of devastating war. The questions, “What happened to Yugoslavia?” and “Why did Yugoslavia break up?” do not yield easy or succinct answers. Instead, they draw attention to a complex interplay of several factors that, cumulatively, led to the country’s disintegration. To elucidate these factors, we embark on a journey through three key facets: the unresolved national issues, the economic crisis that gripped the nation, and the impact of international politics.

The Unresolved National Question

The national question was a deeply rooted problem in the fabric of Yugoslavia that served as a catalyst for its eventual fragmentation. To fully appreciate this issue, it’s essential to delve into the historical background, the socio-political structure, and the simmering ethnonational tensions that prevailed during Yugoslavia’s existence.

Yugoslavia was a federation of six republics – Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia – and two autonomous provinces – Kosovo and Vojvodina. These territories, despite being united under the banner of Yugoslav socialism, were a mosaic of diverse ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups with unique historical experiences, cultural traditions, and national aspirations.

Under the rule of Josip Broz Tito, the Yugoslav government pursued a policy of “brotherhood and unity” that aimed to transcend ethnic differences and cultivate a pan-Yugoslav identity. To that end, they designed a federal structure that granted significant autonomy to individual republics and provinces. Yet, this arrangement only partially resolved the underlying national tensions. In fact, it allowed ethnic nationalism to maintain a certain level of institutional existence within the confines of socialist Yugoslavia.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Test your knowledge of the past with our interactive history quiz! Can you answer all 20 questions?

The national issue was further complicated by the different historical narratives that prevailed among the ethnic groups. For instance, the Serbs and Croats, two of the largest ethnic groups, held conflicting memories and interpretations of the past, particularly concerning World War II. The Serbs remembered the Croat-led Ustaše regime’s brutal massacres, while the Croats resented the Serb-dominated Partisan regime’s post-war retaliatory purges. These historical grievances, though subdued during the Tito era, resurfaced with vengeance following Tito’s death in 1980, fueling inter-ethnic mistrust and hostility.

Another aspect of the national question was the power imbalance among the republics. While Serbia was the most populous republic and held a dominant position in the federation, the 1974 constitution significantly reduced Serbia’s influence over Kosovo and Vojvodina, which were granted nearly the same level of autonomy as the republics.

Towards the end of the 1980s, as the communist regime’s grip on power loosened, ethnic nationalism re-emerged as a potent force in Yugoslav politics. Politicians across the republics began to employ nationalist rhetoric to mobilize support, exacerbating inter-ethnic tensions. The media further inflamed these tensions, which frequently highlighted instances of inter-ethnic violence and promoted nationalist narratives.

In conclusion, the unresolved national question was a deeply complex and multifaceted issue that played a crucial role in Yugoslavia’s disintegration. Despite the Yugoslav government’s attempts to cultivate a pan-Yugoslav identity and manage ethnic differences through a federal structure, the historical grievances, perceived imbalances of power, and the re-emergence of ethnic nationalism eventually led to the federation’s unraveling.

Economic Crisis in the Late ’70s

As the 1970s drew to a close, Yugoslavia found itself confronted with an economic crisis that would test the resilience of its unique socialist experiment and set the stage for the country’s tragic disintegration in the following decade.

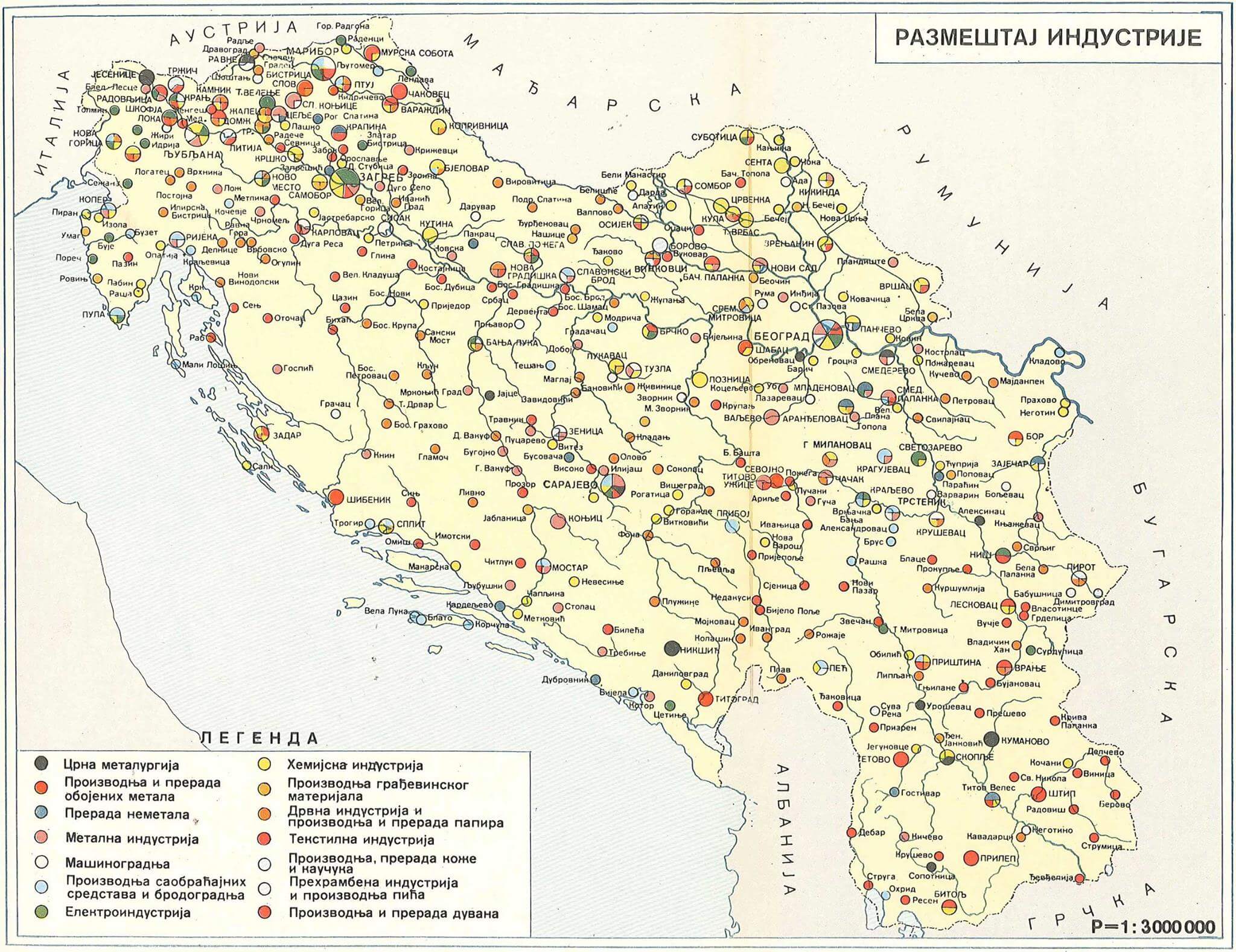

The Yugoslav economy differed significantly from the centralized command economies of the Eastern Bloc. Instead, it was characterized by worker self-management, where workers in enterprises had a say in decision-making, and market socialism, where goods and services were freely traded in markets. This system, hailed as the “third way” between capitalism and state socialism, initially achieved remarkable success, driving rapid industrialization, improving living standards, and ensuring a degree of economic equality.

However, by the late ’70s, this model began to show signs of strain. One of the main factors contributing to the economic crisis was the heavy reliance on foreign loans. In the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis, Western banks were awash with ‘petrodollars’ and were eager to lend to developing nations. Yugoslav authorities, aiming to maintain high growth rates and employment, took on considerable debt. While these loans initially funded industrial growth and infrastructure development, the 1979 oil crisis and subsequent global recession led to increased interest rates and a slowdown in the world economy, exacerbating Yugoslavia’s debt problem.

Moreover, the structure of the Yugoslav economy itself became a source of instability. The decentralization of economic decision-making, while fostering a sense of participation and ownership among workers, led to inefficiencies and made it difficult to implement necessary reforms. Enterprises often prioritized job preservation over productivity and profitability, leading to overemployment and underinvestment. In addition, the absence of effective central fiscal controls meant that individual republics could run large budget deficits, contributing to inflation.

Simultaneously, significant economic disparities between the developed northern republics, like Slovenia and Croatia, and the less developed southern republics, such as Macedonia and Montenegro, fuelled resentment and tension. The wealthier republics felt that their earnings were siphoned off to subsidize the less developed regions, while the poorer republics felt marginalized and exploited.

The economic crisis also had profound political implications. It undermined the legitimacy of the Communist Party and exacerbated the latent ethnic tensions in the federation. As living standards declined, public dissatisfaction grew, and citizens increasingly fell back on their ethnic identities as a source of solidarity. This provided fertile ground for nationalist politicians, who blamed the economic woes on other ethnic groups and promised to protect the interests of their kin.

In conclusion, the economic crisis of the late ’70s was a turning point in the history of Yugoslavia. It exposed the structural weaknesses of the Yugoslav economic model, intensified inter-republic disparities, and eroded public faith in the Communist regime. It laid bare the ethnic fault lines and set the stage for the destructive wave of nationalism that would ultimately tear the country apart.

International Politics and Political Circumstances

As the 1980s unfolded, the world stage was shifting rapidly, caught in the turbulence of a global geopolitical reordering. These tumultuous international politics and political circumstances presented challenges and pressures that further destabilized Yugoslavia, exacerbating its pre-existing internal struggles.

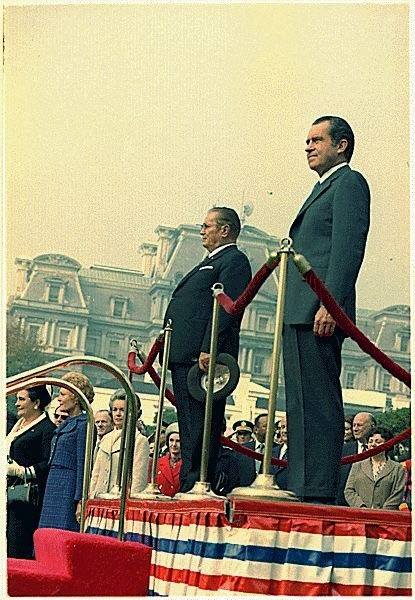

Yugoslavia had always occupied a unique and precarious position in the global political landscape. As a socialist federation that resisted Stalin’s influence, it trod a delicate line between the Eastern Bloc and the Western democracies, leveraging its non-aligned status to maintain a measure of autonomy. This balancing act was achieved largely due to the leadership of President Josip Broz Tito, who managed to play off the superpowers against each other to secure economic and political support.

However, Tito’s death in 1980 sent shockwaves through the federation. The loss of its charismatic leader, who had been a unifying figure and had successfully navigated the international politics of the Cold War, left a leadership vacuum that Yugoslavia struggled to fill. The eight-member collective presidency that succeeded him proved incapable of exerting the same level of control, and regional leaders started vying for more power and autonomy.

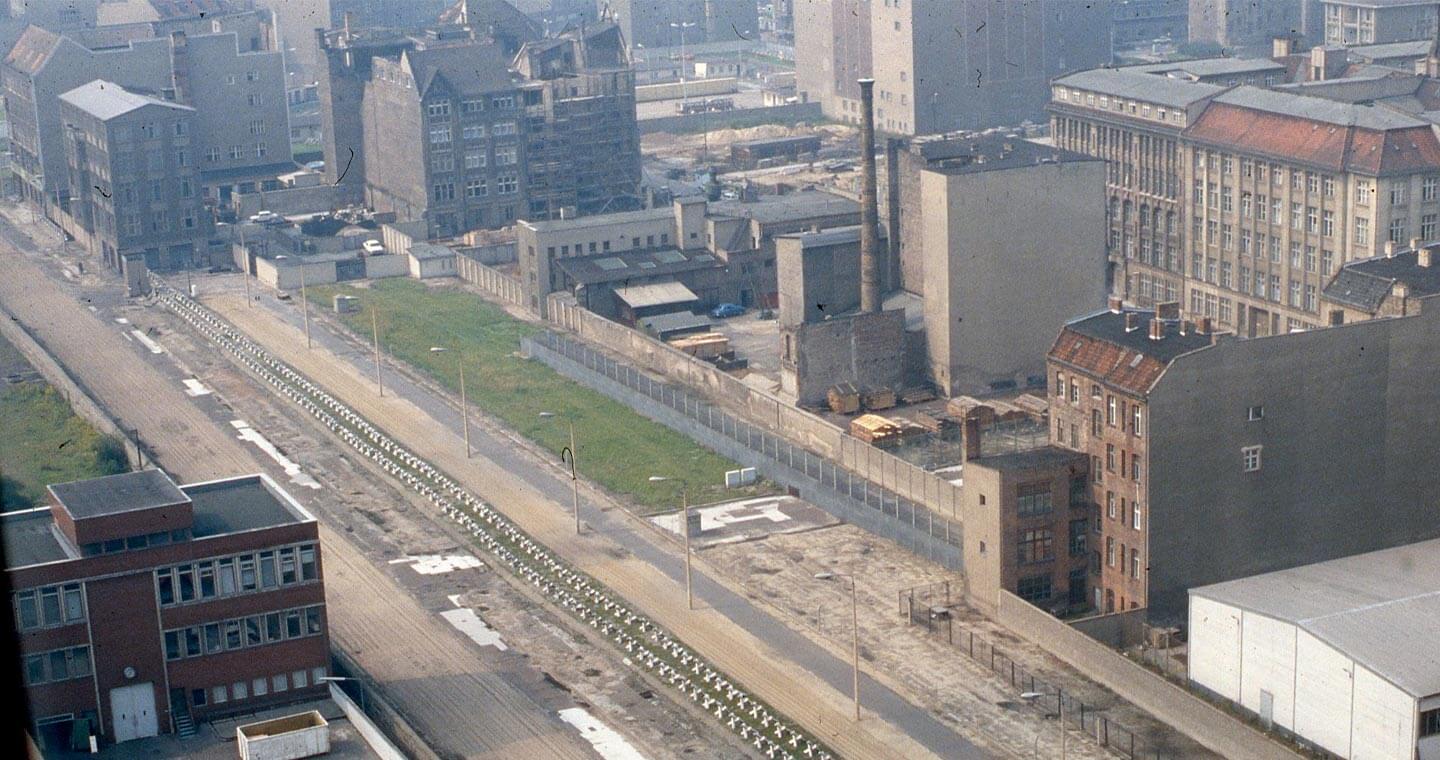

Meanwhile, the international climate was becoming increasingly unfriendly. The 1980s marked the beginning of the end of the Cold War, culminating in the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. As the bipolar world order crumbled, Yugoslavia lost its strategic value and the international leverage it once had.

In addition, the ascendancy of neoliberal economic ideologies in the West during the 1980s, championed by figures like Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US, resulted in a change in international lending practices. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank began to demand market liberalization and austerity measures in return for financial aid. For Yugoslavia, grappling with an economic crisis, these ‘structural adjustment programs’ exerted a devastating toll on the standard of living and social welfare, fueling public resentment and social unrest.

Furthermore, the international community’s approach to the emerging crisis in Yugoslavia was marked by indecision and inconsistency. As the country descended into violence, there was a lack of decisive action from the major powers and international organizations. The United Nations and the European Community struggled to mount an effective response, and their sporadic interventions often had unintended consequences, stoking the conflict rather than quelling it.

In conclusion, the international politics and political circumstances during the 1980s and early ’90s contributed significantly to the pressures facing Yugoslavia. The end of the Cold War, the rise of neoliberal economic policies, and the inconsistent international response all played crucial roles in the country’s tragic demise. As the world watched, a complex interplay of internal struggles and external pressures pushed Yugoslavia towards disintegration.

The Cataclysmic Intersection of Forces

In the solemn disintegration of Yugoslavia, a multitude of intricate and intertwined forces orchestrated a calamitous climax. The raw, unresolved national question unveiled entrenched ethnic and religious animosities, a heritage long subdued beneath Tito’s firm grip, waiting to explode into the forefront of the national narrative. This grievous fault line was further eroded by the persistent economic crises that spanned the late 70s and 80s, inflaming social discontent and fuelling resentment amongst the population. The backdrop to this precarious scenario was the dynamic shifts in international politics and the unfolding geopolitical reordering of the period, which exerted potent external influences and pressures. As these potent forces collided, they constructed an unfortunate trajectory that spiraled uncontrollably, culminating in the heart-wrenching dismemberment of what was once a symbol of unity in diversity – Yugoslavia.