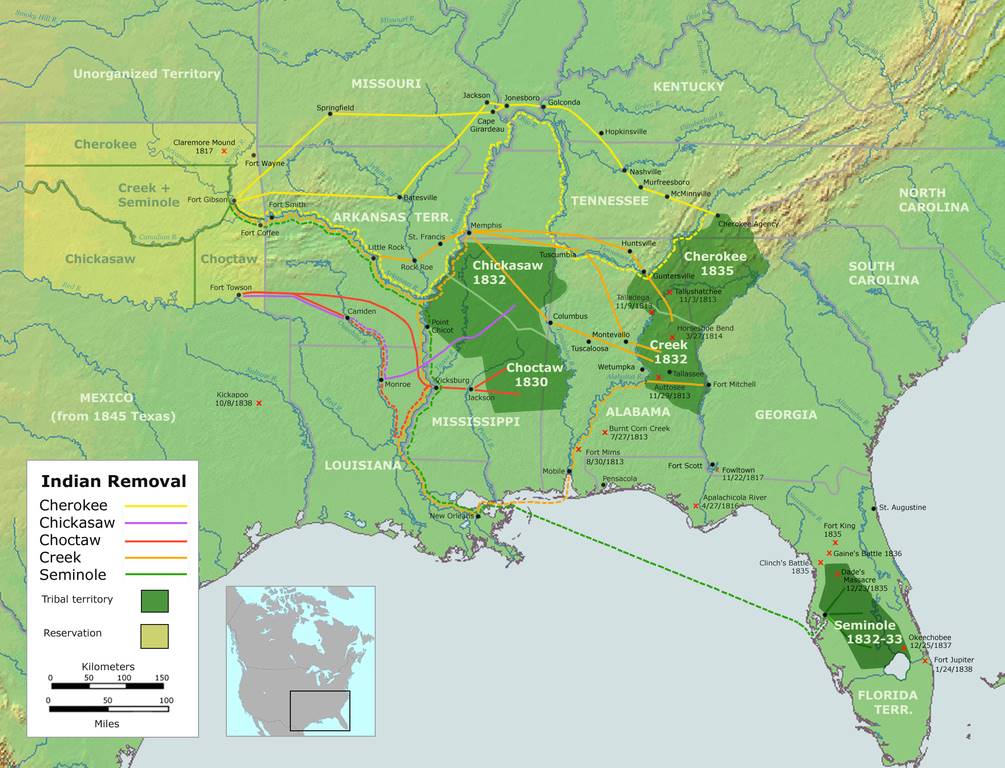

The Trail of Tears stands as one of the most tragic events in the history of the United States, especially when viewed through the lens of the Native American experience. Although the term Trail of Tears is most commonly associated with the Cherokee tribe, it, in reality, encompasses the forced removals of the “Five Civilized Tribes,” as labeled by European settlers. These tribes were the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole.

During this coerced relocation, it is estimated that between 60,000 and 100,000 members of these tribes were moved from their ancestral lands to designated territories in the West. Tragically, it is believed that up to 25% of the relocated individuals, which translates to 15,000 to 25,000 Native Americans, died due to disease, starvation, and exhaustion during the arduous journey.

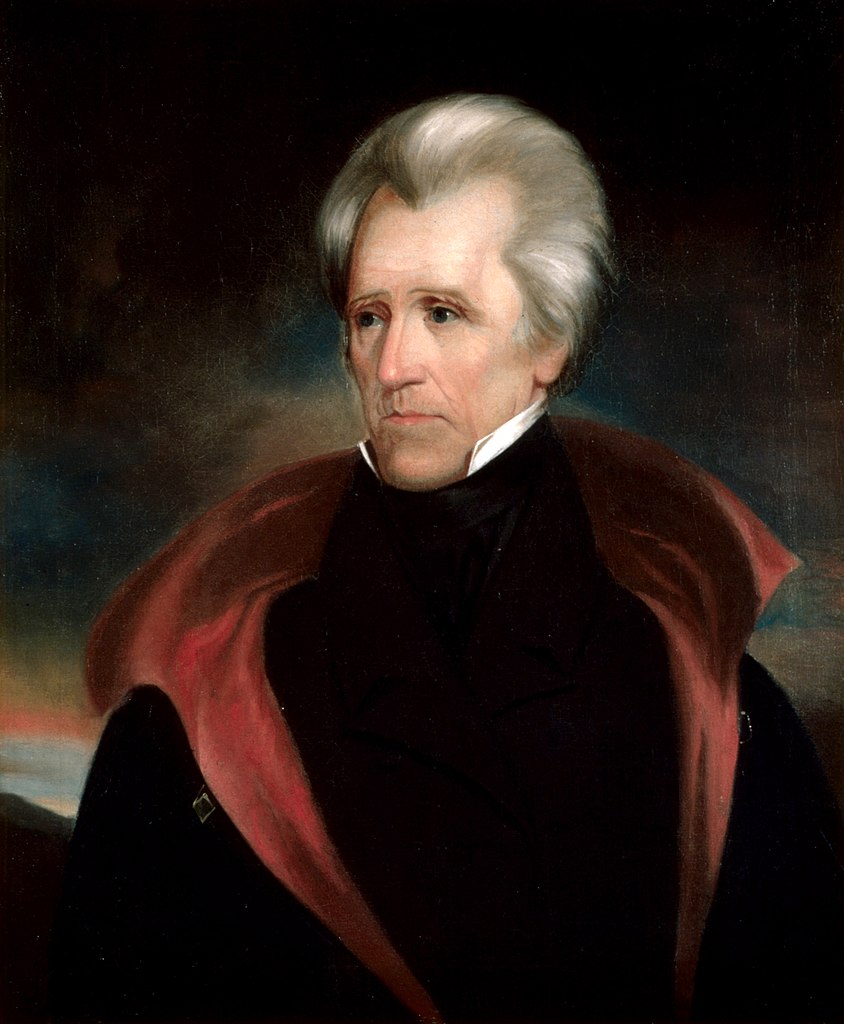

Indian Removal Act and Andrew Jackson

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 stands as one of the most controversial pieces of legislation in American history. Spearheaded by President Andrew Jackson, this act was passed by Congress with the intent to relocate Native American tribes living in the southern states to lands west of the Mississippi River. Jackson’s motivation was twofold: he viewed it as a way to “civilize” the Native American populations, and more pressingly, he recognized it as an opportunity to open vast expanses of fertile lands to white settlers, particularly for the booming cotton industry.

The Act itself, although proposed as a “negotiated” relocation, was far from a fair negotiation in practice. Many treaties, like the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek with the Choctaw in 1830, were ratified under duress or by representatives not fully empowered to sign on behalf of their entire tribe. Consequently, the Choctaw began their forced migration in 1831, becoming one of the first tribes to experience the harsh realities of the Act. Despite significant opposition from various tribes and even notable U.S. government figures like Congressman Davy Crockett and Chief Justice John Marshall, Jackson’s determination saw the policy through.

Tragically, the U.S. frequently did not uphold its end of the treaty agreements. Promised funds for tribal lands often were either severely delayed, insufficient, or never provided. Moreover, the lands designated for resettlement were frequently unsuitable or were already occupied by other tribes, leading to inevitable conflicts. The grim peak of these removals is epitomized by the Trail of Tears between 1838 and 1839, where the Cherokee faced their harrowing relocation, and thousands perished.

The Choctaw Tribe

The Choctaw people are one of the oldest and most historically significant Native American tribes in the southern United States. Originally inhabiting areas that today comprise parts of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama, the Choctaw had a rich culture with complex political structures, religious beliefs, and social practices.

They lived in independent villages with a matriarchal society and built homes, often referred to as “winter houses” or “summer houses”, based on the season. The Choctaw were also renowned for their skills in agriculture, cultivating crops like corn, beans, and squash, which played a pivotal role in their diet and commerce.

The fate of the Choctaw changed dramatically with the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The U.S. government sought their ancestral lands for expansion and economic gain, leading to the signing of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830. This treaty, signed under questionable circumstances, led to the forced relocation of the Choctaw people starting in 1831.

At the time of the removal, the tribe numbered approximately 20,000 members. The journey to their new designated territory, often referred to as the “Choctaw Trail of Tears”, was brutal. Inadequate supplies, diseases, and harsh weather conditions took a devastating toll. By the end of the migration in the mid-1830s, it’s estimated that around 6,000 Choctaw individuals, nearly a third of the entire tribe, had perished. The tragic loss and trauma endured during this time left an indelible mark on the Choctaw’s collective memory and continues to shape their identity and narratives today.

The Creek Tribe

Originating from the southeastern regions of the present-day United States, the Creek, also known as the Muscogee, established themselves in areas that now encompass modern-day Alabama and Georgia. The Creek Confederacy, composed of various towns, emerged as a dominant force in the region. They boasted a rich cultural and agricultural heritage, often centering around staple crops such as corn, beans, and squash.

However, with the U.S. expansion in the early 19th century, especially after the Creek War of 1813-1814, their territories were progressively threatened. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 solidified their displacement. By the Treaty of Cusseta in 1832, the Creek ceded most of their lands, initiating their forced migration to present-day Oklahoma. At the onset of removal, the Creek population was estimated to be around 20,000. The treacherous journey, marked by disease, lack of supplies, and harsh conditions, resulted in the tragic loss of several thousand lives. This harrowing experience remains a somber chapter in the Creek’s enduring legacy.

The Seminole Tribe

The Seminole, native to the Florida peninsula, evolved from a diverse array of Native American groups and runaway African slaves who sought refuge in Florida’s swamps, escaping from southern plantations. This unique mix of cultures made the Seminoles distinct from other southeastern tribes. Living in harmony with the wetlands, they built stilted villages over water and thrived on fishing, hunting, and small-scale agriculture.

However, tensions escalated in the 19th century as American settlers and the U.S. government encroached upon Seminole territories. This pressure led to a series of conflicts known as the Seminole Wars, spanning from 1817 to 1858. Particularly, after the Indian Removal Act of 1830, attempts to relocate the Seminoles intensified.

In response to the removal efforts, the Seminoles, estimated to number around 5,000 at the time, fiercely resisted. Their resistance led to the costliest Indian war in U.S. history, both in monetary terms and in human lives. The majority were eventually forcibly relocated to Oklahoma, with many facing the hardships typical of such relocations: disease, starvation, and exposure. It’s believed that up to half of the Seminoles may have perished during this period, either in conflict or during the treacherous journey. However, a significant number managed to remain in Florida, defying removal, and their descendants continue to reside there to this day.

The Cherokee Tribe

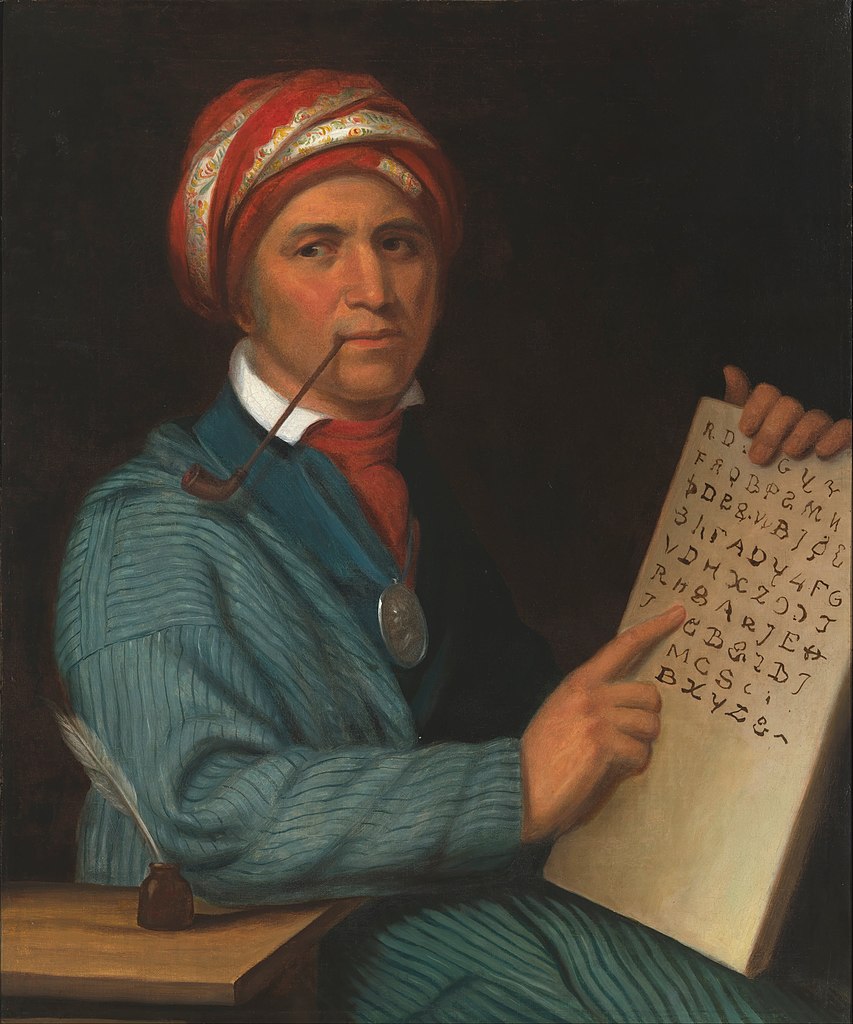

The Cherokee, one of the most prominent and influential tribes in North America, hailed from the southeastern regions, covering the modern-day states of Georgia, Tennessee, and parts of North Carolina. With a sophisticated societal structure, the Cherokees had a written syllabary, developed by Sequoyah, and even published a newspaper, the “Cherokee Phoenix.” They practiced settled agriculture, cultivating a range of crops, and were notable for their legal codification and adoption of a constitution inspired by the United States.

However, the 19th century brought about devastating changes for the Cherokee. As the United States expanded, the lust for Cherokee lands, particularly for cotton cultivation, grew intense. The discovery of gold in Georgia further heightened the settlers’ appetites. In 1830, the Indian Removal Act was passed, and the U.S. government began pressuring the Cherokee to leave their ancestral lands.

Despite legal battles, including favorable rulings from the Supreme Court, President Andrew Jackson’s administration did not enforce these decisions. The Treaty of New Echota in 1835, signed by a minority faction and not representative of the Cherokee nation, sealed their fate. It ceded all Cherokee lands in the southeast in exchange for land in the west.

The subsequent forced removal in 1838-1839 came to be known as the “Trail of Tears.” Of the estimated 16,000 Cherokee who were relocated, around 4,000 perished due to disease, starvation, and exposure during the 1,000-mile trek. This tragic event deeply scarred the Cherokee’s collective memory.

The phrase “Trail of Tears” originated from descriptions of the removal, evoking images of the immense suffering the Cherokee faced. Over the years, it became emblematic of the broader injustices Native American tribes experienced.

In recognition of this harrowing journey and the significance it holds, the “Trail of Tears National Historic Trail” was established in 1987, stretching over 3,540 kilometers, commemorating the route taken by the Cherokee during their forced removal. It serves as both a museum and a testament to the resilience and endurance of the Cherokee people.

In a long-overdue gesture, in 2008, the U.S. Congress formally apologized to the Cherokee and other affected tribes for the suffering they endured during the removals. While the apology can’t reverse the past, it stands as an acknowledgment of the immense pain and injustices the Cherokee and other tribes experienced.

Today, the Cherokee’s legacy, interwoven with tales of tragedy and triumph, resilience, and adaptability, stands as a testament to their indomitable spirit. The term “Trail of Tears” serves as a potent reminder of the price they paid, as well as the resilience of indigenous cultures in the face of overwhelming adversity.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!