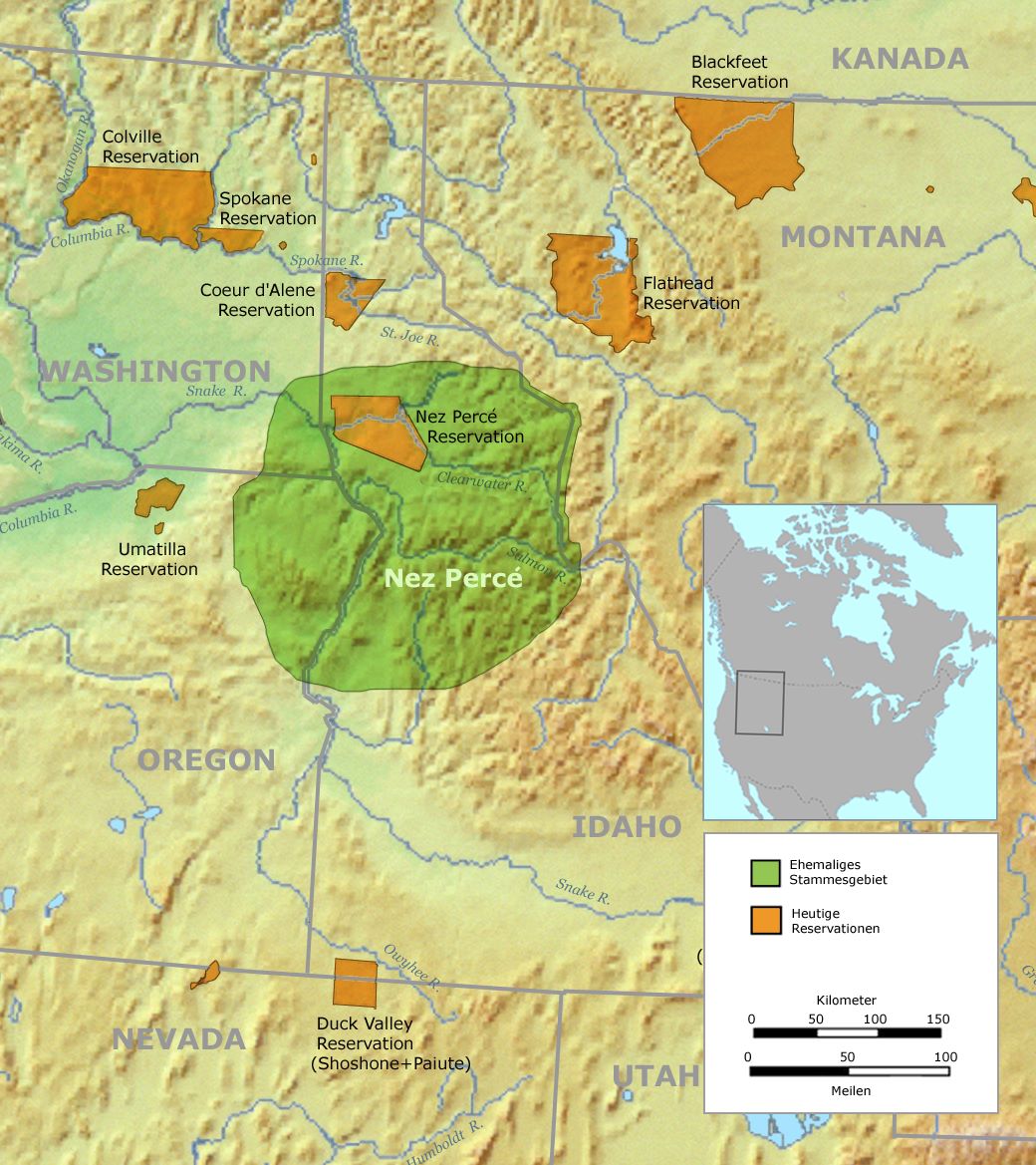

The Nez Perce are a Native American tribe historically based in the Pacific Northwest, primarily in what is today the state of Idaho. Their name, meaning ‘pierced nose’ in French, was given by early French Canadian fur traders, although nose-piercing was not a common practice among the tribe. The first documented contact with Westerners occurred in the early 1800s, with their most notable early encounter being with the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1805. Welcoming and assisting the explorers, the Nez Perce played a pivotal role in the expedition’s successful journey to the Pacific Ocean. Despite their peaceful initial interactions, the Nez Perce’s territory would later become a battleground as they resisted U.S. government efforts to relocate them to reservations.

Lead Up to the War

The Nez Perce tribe traditionally held a favorable disposition towards Euro-Americans. From their early encounters with white settlers, especially during the Lewis and Clark expedition, they exhibited a welcoming attitude and readiness for cooperation. Their allegiance and aid to the white man was so pronounced that they often assisted U.S. forces in conflicts with neighboring Native tribes, further solidifying their ties with the newcomers. However, the discovery of gold on their lands in the late 1860s altered the dynamics of these relationships. Their once relatively isolated territory was rapidly inundated with white gold-seekers, drawn to the region in search of riches, often with little respect for indigenous rights and customs.

Despite efforts from the tribal leadership to maintain peace and stability, tensions between the Nez Perce and the incoming settlers steadily escalated. In the spring of 1877, a young and rogue group of Nez Perce warriors, led by some younger members of the tribe, launched a series of attacks on white settlers, resulting in several deaths. These incidents became the catalyst for an all-out conflict, the Nez Perce War, with the U.S. Army determined to punish those responsible and, more importantly, force the tribe to relocate to a reservation.

Prominent Leaders of the Nez Perce

The Nez Perce leadership during the time of the conflict was comprised of individuals who each had distinct roles and strategies in leading their people.

Chief Joseph (Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it): Undoubtedly the most well-known leader of the Nez Perce, Chief Joseph was an advocate for peace. His eloquence and diplomacy are legendary, and he remains an iconic figure in American history. His primary aim during the conflict was to lead his people to safety in Canada, away from U.S. military pursuit.

Looking Glass (Allalimya Takanin): A respected war leader and strategist, Looking Glass had a significant influence on the Nez Perce’s military strategies. He was not initially in favor of the war but joined the resistance with full commitment after the U.S. Army preemptively attacked his village.

Toohoolhoolzote: This influential leader was known for his strong oratory skills and was a vocal opponent of U.S. encroachments. His arrest by the U.S. military without proper cause exacerbated tensions between the Nez Perce and the American government.

The primary aim of these leaders during the conflict was unified: to protect and secure the future of the Nez Perce people. Initially, many tribal leaders wanted peace and were willing to negotiate with the U.S. government. However, as the situation deteriorated, the idea of a strategic retreat emerged, with the hope of evading the pursuing U.S. forces and seeking refuge in Canada.

Each leader, while sharing the common goal of the welfare of their people, had varied perspectives on how to achieve this. While some like Chief Joseph believed in diplomacy, others saw the merit in direct confrontation.

The Retreat of the Nez Perce

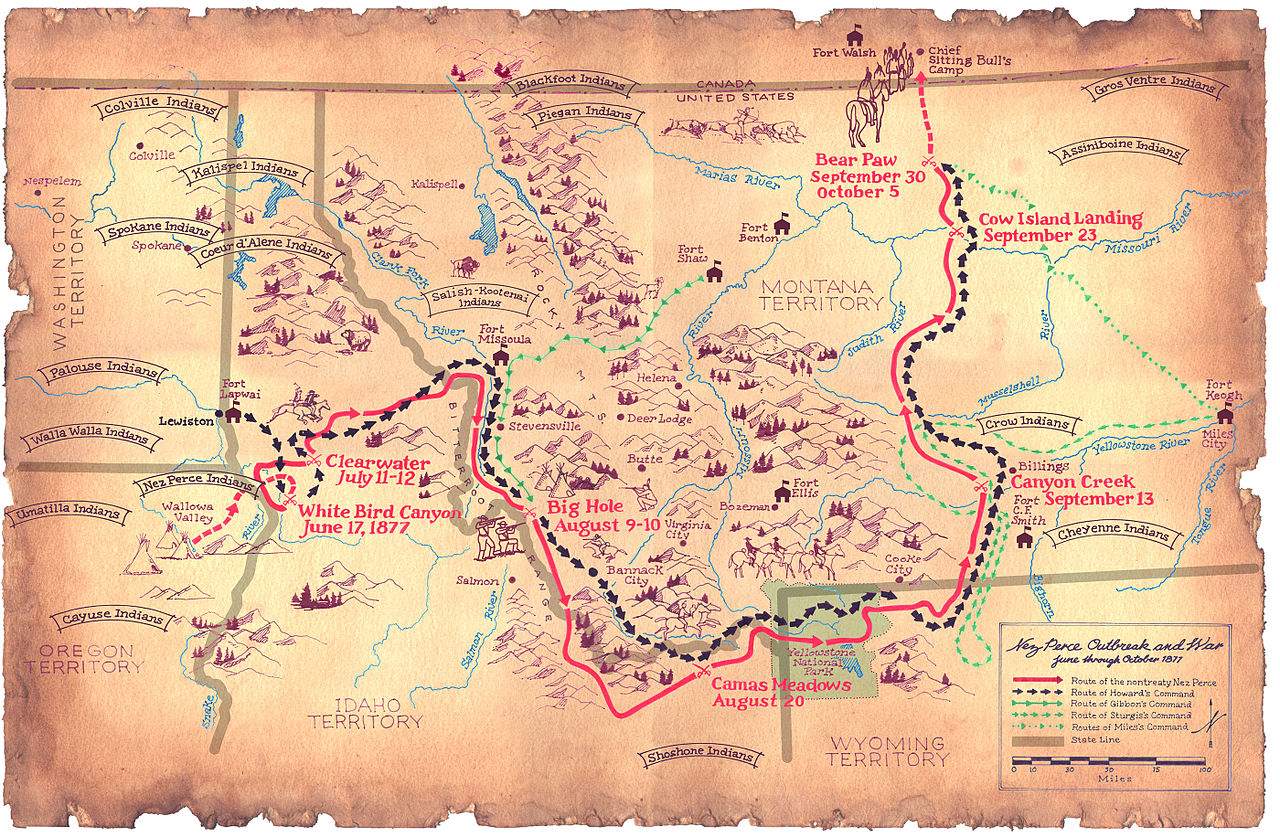

The Nez Perce War was not simply a series of battles but also a tactical retreat over vast territories. The war unfolded over a span of several months and saw the Nez Perce adopting guerrilla tactics, retreating, and clashing with U.S. forces repeatedly.

The tribe’s journey spanned over 1,170 miles across Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana. Of the Nez Perce involved in this trek, there were approximately 800 individuals, but only around 250 of these were warriors. The remainder comprised women, children, and the elderly—civilians on the move, trying to escape the relentless pursuit of the U.S. military.

Throughout this arduous journey, the Nez Perce engaged the U.S. Army in several significant battles and countless skirmishes. Key encounters included the Battle of White Bird Canyon, the Battle of the Clearwater, the Battle of the Big Hole, and the Battle of Bear Paw, among others. Despite being heavily outnumbered in many of these engagements, the Nez Perce exhibited remarkable military prowess, often outmaneuvering and out-strategizing their opponents.

The nature of this warfare and the discipline of the Nez Perce drew admiration from even their adversaries. General William Tecumseh Sherman, a key figure in the U.S. military, said of the conflict:

“One of the most extraordinary Indian Wars of which there is any record. The Indians displayed courage and skill that elicited universal praise. They abstained from scalping: let captive women go free; did not commit indiscriminate murder of peaceful families, which as usual, and fought with almost scientific skill, using advance and rear guards, skirmish lines and field fortifications.”

This commendation by Sherman underscores the exceptional strategic abilities of the Nez Perce warriors and their commitment to a form of warfare that was, by the standards of the day, chivalrous and honorable. The Nez Perce’s strategy was primarily defensive, aiming to secure the safe passage of their people rather than to vanquish their pursuers.

The Battle of Bear Paw and Chief Joseph’s Surrender

The Battle of Bear Paw, which took place between September 30 and October 5, 1877, marked the final major confrontation between the Nez Perce and U.S. military forces. It was, in the cold terrains of Montana, just 40 miles shy of the Canadian border, that the desperate dreams of the Nez Perce for sanctuary would be halted.

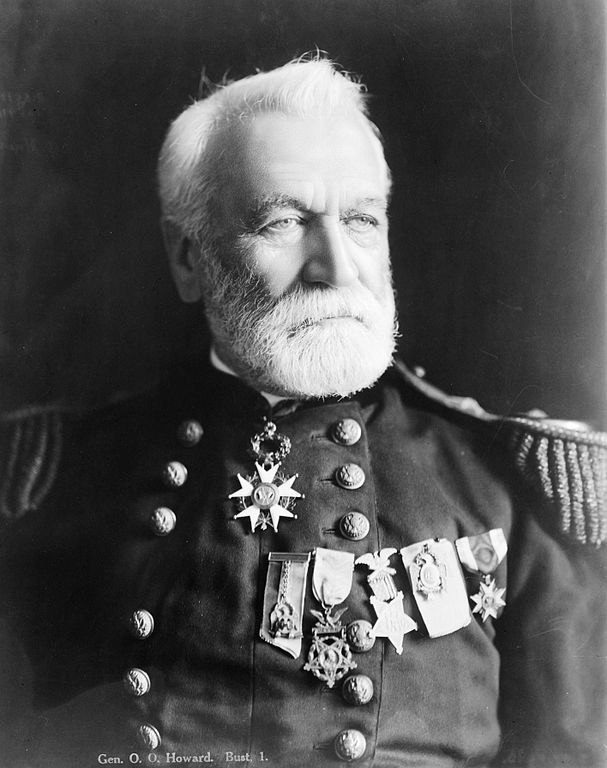

Having traversed over a thousand miles with the hope of reaching safety, the Nez Perce established a defensive position in the Bear Paw Mountains. U.S. Army forces, under the command of General Oliver O. Howard, engaged the Nez Perce in a fierce five-day battle, characterized by heavy combat and brutal weather conditions. The tribe’s warriors, despite their exceptional strategies and guerilla tactics, were increasingly exhausted, with their numbers dwindling due to the sustained pursuit.

On October 5th, surrounded and outnumbered, the Nez Perce made the heart-wrenching decision to surrender. It was in this backdrop of defeat, with the weight of the journey and the losses bearing down upon them, that Chief Joseph delivered one of the most poignant and eloquent speeches in American history.

Addressing General Howard and the surrounding audience, Chief Joseph said:

“Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Tu-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men [Ollokot] is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

The profound sorrow and fatigue evident in Chief Joseph’s words resonated deeply with all who heard it, encapsulating the tragedy of the Nez Perce’s long struggle and their eventual capitulation. His statement remains a testament to the courage, endurance, and spirit of the Nez Perce people and serves as a poignant reminder of the costs of expansion and conflict.

Chief Joseph’s Pleas and the Final Years of the Nez Perce

After the harrowing events of the Nez Perce War and the subsequent surrender, Chief Joseph’s leadership took on a different dimension. No longer was he leading his people in battle, but he became their voice, advocating for their rights and dignity in the political arena.

In January 1879, Chief Joseph traveled to Washington, D.C., with hope and a plea. He intended to petition the U.S. government to allow the Nez Perce to return to their native lands in Idaho or, failing that, to at least be provided lands in what would later become Oklahoma. In his quest for justice, Chief Joseph met with the President and members of Congress. His moving account of the Nez Perce’s trials and tribulations was published in the *North American Review*, introducing a wider audience to the tribe’s plight.

While in Washington, Chief Joseph was met with acclaim and admiration, his articulate pleas resonating with many. However, the political reality was harsher. Opposition in Idaho was fierce, and the U.S. government, unwilling to go against this sentiment, denied his petition. Instead of being allowed to return to their ancestral lands, Joseph and his people were sent to Oklahoma. They were settled on a small reservation near Tonkawa, where the scorching conditions were hardly an improvement over the previous hardships they had faced at Leavenworth.

The story of the Nez Perce, however, found a silver lining, albeit a bittersweet one. In 1885, after years of exile, Joseph and 268 of the surviving Nez Perce were granted permission to return to the Pacific Northwest. But this return came with a caveat for Chief Joseph. He was not allowed to settle on the Nez Perce reservation, the land of his ancestors and the place he had fought so hard for. Instead, he was relocated to the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington.

It was here, on this foreign land, that one of America’s most iconic indigenous leaders passed away in 1904. Chief Joseph’s legacy, however, lives on—a testament to resilience, leadership, and the undying hope for justice.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!