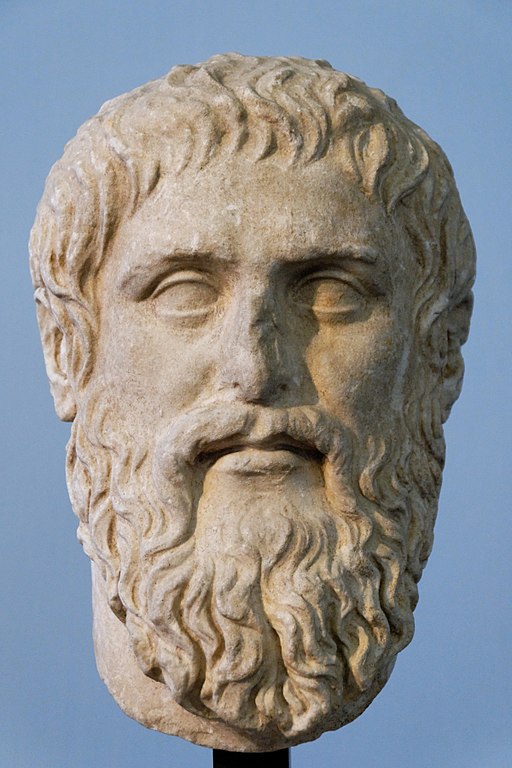

The tale of the ancient Atlantis has captivated imaginations for nearly 2,500 years, ever since its first mention by Plato in his dialogues “Timaeus” and “Critias”. This legendary civilization has been a focal point of intrigue, leading scholars and enthusiasts alike to propose countless potential locations across the globe. Daily, new sites are suggested as the possible remnants of this lost city, placing Atlantis virtually everywhere on Earth. Yet, amidst the realms of speculation and pseudohistory, one location stands out to historians as having substantial potential: the Greek island of Santorini. Let us explore why Santorini is considered by many to be the true Atlantis.

Plato’s Atlantis

In his dialogues “Timaeus” and “Critias,” Plato relays the story of Atlantis as recounted by the Athenian statesman Solon, who learned of it from Egyptian priests. The priests described Atlantis as a powerful empire existing 9,000 years before their time, which flourished just beyond the Pillars of Hercules. The island was larger than Libya and Asia combined, featuring a perfect climate that supported abundant water and lush forests. This richness of natural resources facilitated the rise of a highly advanced civilization, surrounded by impressive mountains that shielded it from external threats.

Atlantis was architecturally magnificent, with its capital city designed in concentric circles of land and sea, allowing for efficient movement and formidable defense. Central to the city was a grand temple dedicated to Poseidon, extravagantly adorned with gold, silver, and precious ornaments. Tragically, the civilization met its demise through a cataclysmic event. According to Plato, in a single day and night of misfortune, earthquakes and floods swallowed up the island, causing Atlantis to sink into the sea, lost forever.

Minoan Civilization and Santorini

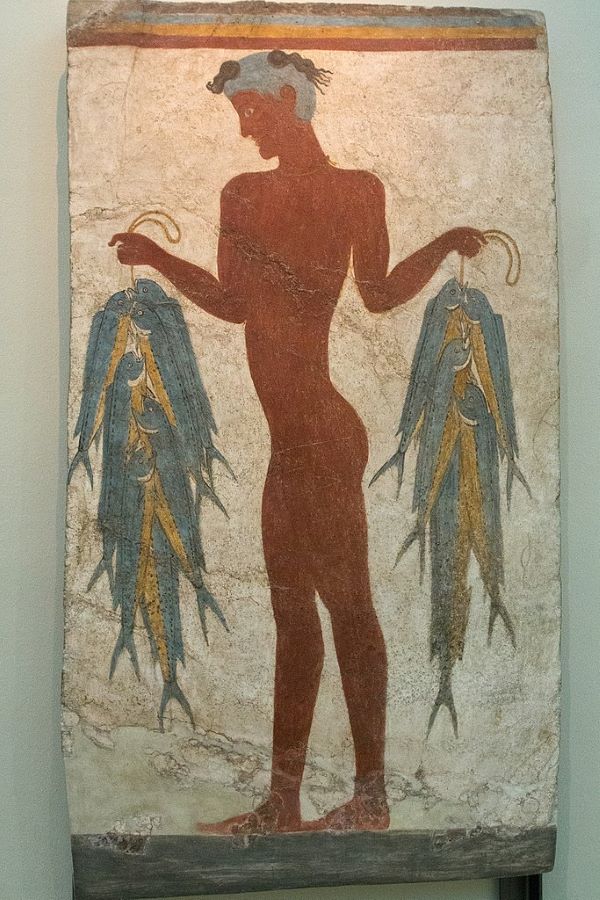

The Minoan Civilization, flourishing from approximately 2600 to 1450 BC, was an advanced Bronze Age society centered on the island of Crete. Known for its significant contributions to European ancient history, the Minoans were pioneers in building elaborate palaces, some of which featured complex plumbing systems, like those found at Knossos. Their art and pottery are distinguished by vibrant colors and intricate designs, reflecting a society rich in culture and steeped in maritime trade. The Minoans developed a script known as Linear A, which remains undeciphered but underscores their advanced administrative capabilities.

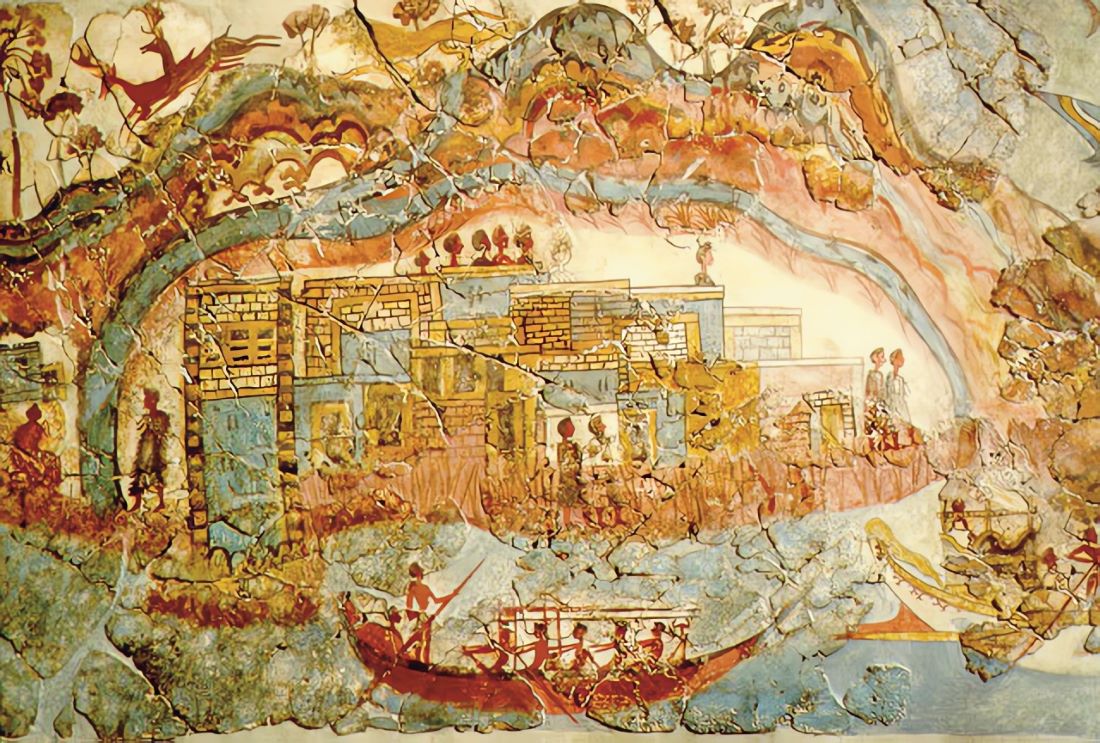

Santorini, then known as Thera, was an integral part of the Minoan Civilization, particularly evidenced by the city of Akrotiri. Preserved remarkably well under layers of volcanic ash, Akrotiri offers a snapshot into Minoan life and architecture. This prehistoric city showcases multi-story buildings, sophisticated urban planning, and elaborate frescoes that depict everyday life as well as natural and religious themes. The eruption on Thera around 1628 BC not only devastated Akrotiri but also significantly impacted the Minoan centers on Crete, possibly contributing to their eventual decline. This catastrophic event and the advanced state of Minoan society in Santorini have led some historians to speculate on the connections between Thera’s fate and the legend of Atlantis.

Is Santorini Plato’s Atlantis?

The hypothesis that Santorini could be Plato’s lost Atlantis draws on a series of catastrophic events that align with the dramatic descriptions of Atlantis’s sudden disappearance. The volcanic eruption on Santorini around 1628 BC was one of the most massive volcanic events the Mediterranean has ever witnessed. It devastated the island, burying the advanced Minoan settlement of Akrotiri under layers of ash and pumice, much like the sudden destruction described in Plato’s account of Atlantis.

This eruption was so colossal that its effects would have been visible and impactful even in distant Egypt. Historical and geological evidence suggests that the eruption triggered a tsunami and caused significant climatic changes, phenomena capable of impressing contemporary observers across the region. The ash cloud and subsequent cooling would have been notable even in the Nile Valley, potentially being recorded in Egyptian records. This could explain how a story of such a disaster might have traveled to Egypt, transforming over time into the narrative of a lost civilization submerged by the gods as a form of divine retribution.

Furthermore, some historians propose that there might have been a mistranslation or misinterpretation of the time scales reported by the Egyptian priests to Solon, suggesting 900 years before Plato’s era rather than 9,000. This time frame would align more closely with the Theran eruption, offering a feasible timeline for the events that could have inspired the Atlantis legend. It is plausible that survivors from Crete and other Minoan territories, fleeing the volcanic destruction, brought tales of their high civilization’s sudden demise to Egypt, melding their actual experiences with existing myths and cultural memories.

Concluding whether Santorini is indeed the lost Atlantis posited by Plato is challenging. The coincidences between the Theran eruption and Plato’s description are compelling, yet they are not conclusive proof. Historical analysis must consider both the similarities and the discrepancies in the geographical and temporal descriptions provided by Plato. However, the theory that Santorini’s cataclysmic event could have sparked the enduring legend of Atlantis remains a tantalizing possibility, inviting both scholars and enthusiasts to continue exploring the echoes of the past that resonate with this enigmatic tale.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!