Every nation has figures in its history who are viewed as heroes by some and traitors by others. For Canadians, Louis Riel is a quintessential example of such a polarizing figure. Riel, a Métis leader, is celebrated for his fierce defense of the rights and culture of the Métis people. However, his actions, particularly during the Red River Rebellion and the North-West Rebellion, led others to view him as a traitor to Canada. This complexity makes Riel an intriguing subject of historical debate and national memory in Canada.

Louis Riel and the Métis People

The Métis people are a distinct cultural group in Canada, formed from the union of European settlers, mainly French and Scottish, and Indigenous peoples, primarily from Cree, Ojibwe, and Saulteaux tribes. This unique blending of cultures began in the 18th century, mainly in the area known as the Red River Settlement, which is now part of modern-day Manitoba. The Métis developed their language, Michif, primarily a mix of Cree and French, and they established a vibrant culture with a strong focus on hunting and trading. The Métis were not only integral in the fur trade era but also played a crucial role in shaping the Canadian West.

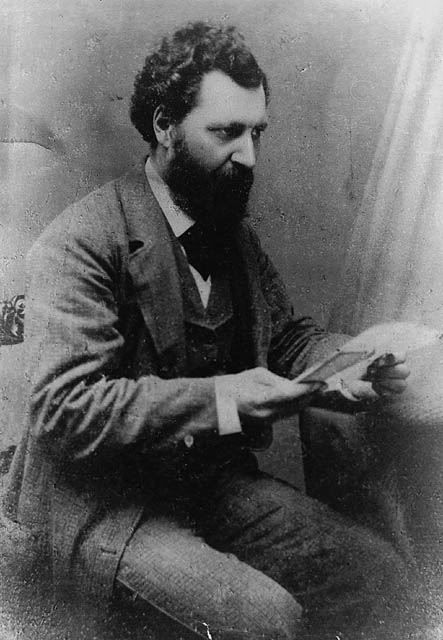

Louis Riel emerged as a central figure in Métis history during the 19th century. Born in 1844 in the Red River Settlement, Riel was educated in Montreal but returned to his homeland to champion the rights and culture of the Métis people. His leadership came into prominence during the Red River Rebellion of 1869-1870. This uprising was a response to the Canadian government’s plans to annex the territory without properly consulting its inhabitants, especially the Métis. Riel’s role in this rebellion, and his efforts to establish a provisional government to negotiate with Canada, marked the beginning of his legacy as both a defender of Métis rights and a controversial figure in Canadian history.

The Tumultuous Journey of the Red River Resistance

As the Red River Resistance unfolded, it became a defining moment in the history of the Métis people and Canada. The Métis, feeling marginalized and ignored by the Canadian government’s expansionist policies, rallied under Louis Riel’s leadership. This resistance was not just a political rebellion; it was a fight for the recognition and preservation of Métis culture, land rights, and identity. The resistance grew out of deep-seated grievances, with the Canadian government’s actions catalyzing the Métis and other settlers in the Red River Settlement to demand a voice in their governance and future.

Riel’s provisional government, formed during this period, was a bold step towards self-determination. It reflected the Métis’ desire for a democratic and inclusive society, contrary to the Canadian government’s initial plans for the region. The negotiations between Riel’s government and Canada were fraught with tension and complexities, reflecting the broader struggles between Indigenous rights and colonial expansion. These negotiations eventually led to the Manitoba Act, which was both a compromise and a testament to the Métis’ resilience and political acumen. However, the act failed to fully resolve the issues at stake, leading to ongoing conflicts and the marginalization of the Métis in subsequent years. The legacy of the Red River Resistance thus remained complex and bittersweet, marking both a significant achievement and a continuing struggle for the Métis people.

The climax of the Red River Resistance was tragically marked by the execution of Thomas Scott, an event that significantly impacted the course of the uprising and its aftermath. Scott, an Ontario settler and a vehement opponent of Riel and the Métis provisional government, was captured and court-martialed by Riel’s forces. Despite pleas for clemency, Scott was executed in March 1870, a decision that Louis Riel personally sanctioned. This act was a turning point in the resistance, significantly altering its nature and perception, especially among English-speaking Canadians in Ontario, where Scott was seen as a martyr. The execution inflamed public opinion against Riel and the Métis, leading to increased military and political pressure on the resistance.

The aftermath of Scott’s execution was swift and severe. It not only deepened the divisions between the Métis and other Canadian settlers but also led to the Canadian government’s dispatched a military expedition to the Red River Settlement. This show of force effectively quelled the resistance and led to the disbandment of Riel’s provisional government. The heightened tensions and the arrival of Canadian troops forced Louis Riel to flee into exile, marking the end of the immediate resistance but setting the stage for future conflicts. Riel’s flight into exile was a significant moment, symbolizing both the temporary suppression of the Métis’ fight for their rights and the enduring impact of their struggle on Canadian history.

The North-West Rebellion: Riel’s Final Stand

After fleeing Canada, Louis Riel spent several years in exile in Montana, United States. During this time, he attempted to lead a quieter life, distancing himself from the political turmoil in Canada. However, the plight of the Métis people in Canada remained unresolved. By the early 1880s, the situation for the Métis in the Saskatchewan region had deteriorated significantly, with increasing discontent over land rights, diminishing buffalo herds, and the Canadian government’s failure to address their grievances. In 1884, a group of Métis leaders, aware of Riel’s previous leadership in the Red River Resistance, traveled to Montana to implore him to return and lead a new resistance. Riel, moved by their plight and convinced of the need for action, agreed to return to Canada.

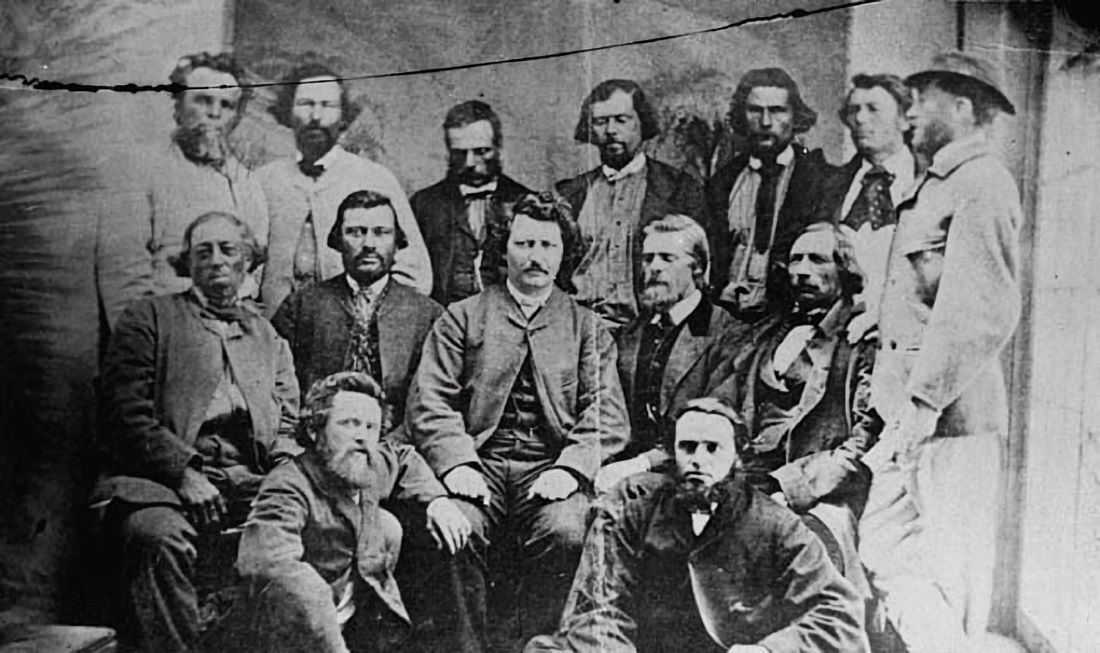

Upon his return, Riel set about organizing the North-West Rebellion of 1885. He gathered around 400 Métis and First Nations fighters, establishing a provisional government similar to the one during the Red River Resistance. The rebellion began with a series of armed engagements against Canadian forces, the most notable being the Battle of Batoche in May 1885. Despite initial successes, the rebels were significantly outnumbered and outgunned by the Canadian forces, which now had better infrastructure, including railways, to move troops quickly. The rebellion was swiftly crushed, with the Battle of Batoche marking its decisive end. The defeat of the Métis forces led to the capture of Louis Riel, who surrendered to Canadian authorities.

Riel’s capture led to a highly controversial and politically charged trial. He was tried for treason in Regina, despite widespread debates over the legitimacy of the trial and calls for clemency from various quarters. Ultimately, Riel was found guilty and sentenced to death. His execution in November 1885 provoked a national outcry and deepened the divisions between French and English-speaking Canadians. Riel’s execution marked not only the tragic end of a charismatic and complex leader but also symbolized the suppression of the Métis’ struggle for recognition and rights. The legacy of the North-West Rebellion and Riel’s martyrdom continues to resonate in Canadian history, symbolizing the ongoing challenges of addressing historical injustices and fostering reconciliation.

Louis Riel’s Legacy in Modern Canadian Society

Louis Riel’s legacy has undergone significant transformation in Canadian society over the years. Initially dismissed as a rebel by Canadian historians, Riel is now often sympathized with as a Métis leader who fought to protect his people from the Canadian government’s encroachment on their lands. His execution in 1885 has had a lasting impact on Canadian history, making him a martyr for the Métis people and influencing political and societal changes, especially in Central Canada. This shift transformed Riel from a figure of controversy—once hated as a “traitor” and the “murderer” of Thomas Scott—to being recognized as a Father of Confederation, a defender of his people, and a protector of minority rights in Canada.

In Manitoba, Riel is commemorated with statues and a public holiday held annually in February. For the Métis, November 16, the day of Riel’s execution, is a day of national commemoration of his life and struggles. He remains the most famous Métis leader and a significant figurehead for the Métis people in Western Canada. Riel’s role in Canadian history is now seen more positively, with many viewing him as a hero embodying contemporary issues like bilingualism, multiculturalism, and social justice. However, some Métis scholars critique the extent to which Riel has been “Canadianized,” noting that this may be at odds with his political beliefs, which prominently featured Métis nationalism and political independence.

Since the 1960s, Riel’s story has seen dramatic shifts in perception. His status as a rebel has largely been replaced by recognition of him as a visionary whose principles resonate with many Métis and Canadians today. Métis writers have played a crucial role in reclaiming Riel’s narrative, highlighting his contributions to multiculturalism and multilingualism. Discussions about Riel’s mental health, once a focal point, have shifted, with contemporary interpretations understanding it within the cultural context of Métis religiosity and the period.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!