Life in Sparta uniquely blended rigid discipline, societal roles, and military might. From the earliest stages of life, Spartans were conditioned to be warriors, with a society that prioritized strength and loyalty to the state. Women in Sparta held unique positions of power and respect, contrasting with the typical roles of women in other ancient civilizations. Yet, beneath the veneer of military prowess lay the complex dynamics with the Helots, the enslaved majority who played a crucial role in maintaining the Spartan way of life.

Childhood and the Agoge: The Spartan Rite of Passage

In the ancient city-state of Sparta, childhood was markedly different from other parts of Greece. From birth, a Spartan’s life was dominated by the state and its relentless pursuit of creating the perfect warrior. Children were assessed immediately after birth, and those deemed weak or with physical disabilities were left on the mountainside, a testament to society’s obsession with physical prowess.

The Agoge, starting at the age of seven, was the rigorous education and training program all Spartan boys were subjected to. It was more than just a school; it was an institution that instilled discipline, endurance, and martial prowess. Boys were taken from their families and lived in communal barracks, forging bonds that would last a lifetime. They were subjected to rigorous physical training, taught survival skills, and conditioned to endure hardship. The Agoge was not just about fighting; it also inculcated values of loyalty, camaraderie, and dedication to Sparta.

Spartan girls, though not enrolled in the Agoge, were also subjected to a form of education that was unique in the ancient world. They were trained in physical activities like running, wrestling, and throwing the javelin. This physical training was believed to ensure that they would produce strong offspring, reinforcing the idea of Sparta’s commitment to creating robust warriors. Additionally, it was thought that a physically fit woman would better endure childbirth, which was crucial in a society that valued population growth for its military.

In essence, childhood in Sparta was not a time of innocent play and leisure. It was a preparatory phase, sculpting young minds and bodies for the challenges of adult life in a warrior society. Every aspect of their upbringing, from the brutal Agoge to the physical training of girls, was geared towards the perpetuation of Sparta’s military might and societal ideals.

The Role of Spartan Women: Beyond Household Duties

Spartan women enjoyed a status, freedom, and education that was unparalleled in the ancient world. Unlike their counterparts in other Greek city-states, where women were primarily confined to the household, Spartan women held significant sway in both the domestic and public spheres.

Economically, Spartan women had considerable power. Due to the extended absences of their husbands and sons, who were often engaged in military training or warfare, women managed the household and family estates. They controlled the finances, made important decisions related to property, and could even become landowners. This economic power inevitably translated to social influence, allowing Spartan women to have a voice in a society that was otherwise dominated by militaristic values.

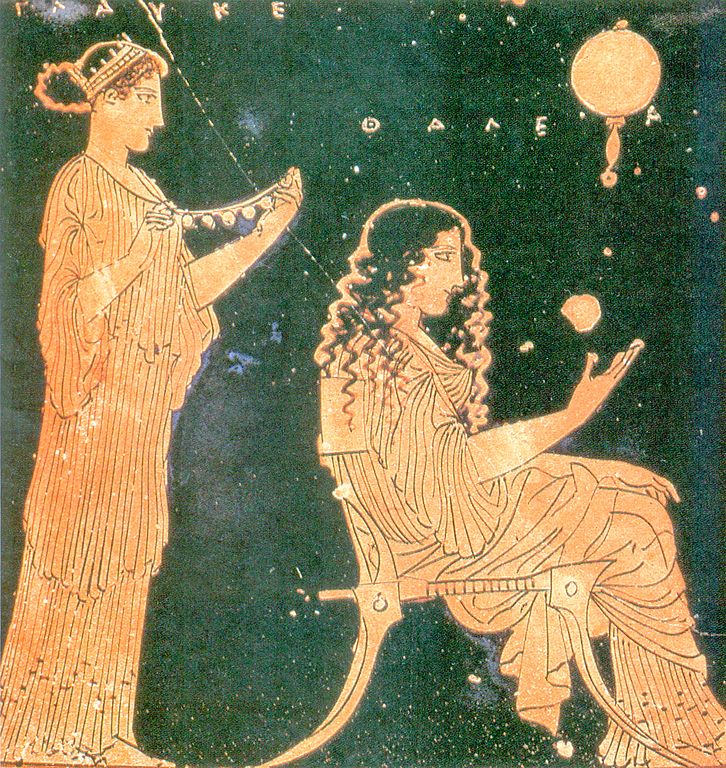

Educationally, Spartan girls were provided with a formal training regimen that focused on physical fitness, but they were also taught music, dance, and poetry. Such education not only prepared them physically for motherhood but also made them intellectually compatible with their warrior counterparts. These women were expected to be the backbone of Spartan society, raising strong children and supporting their warrior husbands, brothers, and sons. Their outspoken nature and confidence were often noted by visitors from other Greek states, with many expressing a mix of admiration and shock at the freedoms and rights Spartan women enjoyed.

Despite their unique position, Spartan women were still primarily valued for their role in reproduction. The primary objective was to produce strong and healthy offspring for the state. They were celebrated for giving birth to sons, who would grow to be warriors, and were often openly encouraged to take multiple partners if their husbands were away, to ensure continuous procreation. Their strength, both physical and mental, was seen as directly contributing to the strength of the entire Spartan state.

In conclusion, Spartan women defied the traditional roles seen elsewhere in ancient Greece. Their influence, derived from their economic and social responsibilities, made them integral to the functioning and continuation of the Spartan way of life. They were more than just mothers or wives; they were pillars upon which the strength and success of Sparta rested.

Warriors and the State: The Military Lifestyle of Sparta

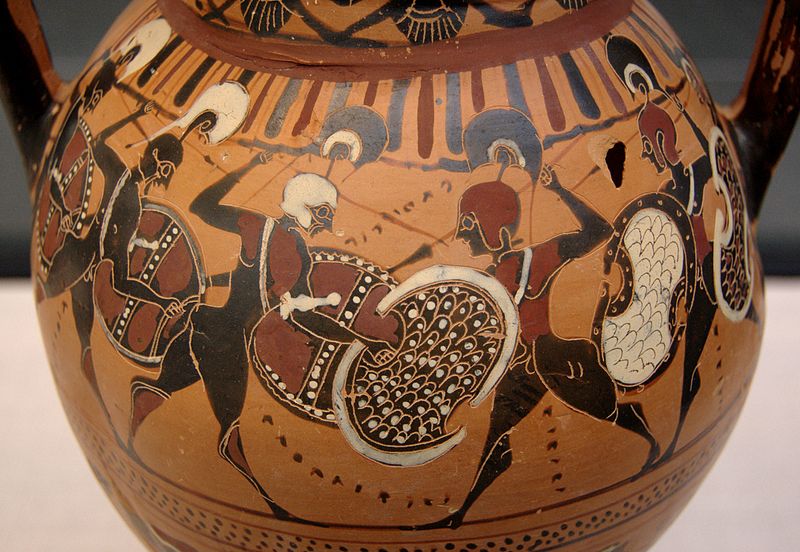

The military was the very heartbeat of Sparta. In a world where city-states constantly vied for dominance, Sparta stood out not just because of its formidable army, but also due to the entire societal structure that supported this military machine. Every facet of Spartan life, from childhood to old age, was influenced by or in service to the state’s martial ambitions.

From the age of 20, all Spartan men became members of the state’s standing army and began their service in communal mess halls known as *syssitia*. These mess halls were more than just dining facilities. They were centers of camaraderie, ideological indoctrination, and communal bonding. Men ate, discussed, and formed strategic partnerships here, strengthening the unity and resolve of the Spartan army. They would serve actively until the age of 60, a testament to the lifelong commitment expected from every Spartan citizen.

While most Greek city-states relied on citizen militias mobilized only in times of war, Sparta’s standing army was a professional force, constantly trained and always ready. Their iconic red cloaks, bronze shields, and strict phalanx formation became symbols of military precision and discipline. Their reputation was so formidable that the very presence of Spartan warriors on the battlefield could sway the morale of both allies and enemies. They weren’t just fighters; they embodied the ideals of sacrifice, discipline, and loyalty to the state.

However, the intense militarization came with its costs. Individual desires, emotions, and personal ambitions were often suppressed for the greater good of Sparta. The arts, philosophy, and personal freedoms that flourished in other parts of Greece were sidelined in Sparta. While cities like Athens reveled in philosophical debates, artistic endeavors, and democratic processes, Sparta’s singular focus was its military might.

In summary, the Spartan military was not just a collection of warriors; it was the very essence of the state. The societal infrastructure, the education system, and even personal relationships in Sparta were all geared toward supporting and maintaining this military powerhouse. While this gave Sparta a formidable reputation in the ancient world, it also defined the limitations of its culture and societal growth.

Physical Training and Discipline: The Pillars of Spartan Strength

In Sparta, the importance of physical prowess was not merely a value; it was a foundational ethos that permeated every layer of society. The relentless focus on physical training and discipline set Spartans apart from their contemporaries and shaped the identity of the entire city-state.

From an early age, Spartan children were introduced to a rigorous regimen of physical exercise. The Agoge, which began at age seven for boys, was only the start. The training involved running, jumping, discus throwing, wrestling, and other forms of combat training. These exercises were not just about building muscle or stamina; they were designed to inculcate resilience, grit, and a capacity to endure pain and hardship. Hunger, fatigue, and even physical beatings were commonplace, serving to weed out the weak and mold the survivors into formidable warriors.

However, physical training in Sparta was not limited to males. Spartan women, as mentioned earlier, were also subjected to their own regimen. The state believed that strong women would give birth to strong children, furthering the lineage of elite warriors. Activities like racing, wrestling, and other athletic competitions were organized for women, a practice that was both unique and controversial in the ancient Greek world. These events, often held in public, underscored Sparta’s commitment to physical excellence across genders.

The discipline that accompanied this training was just as crucial. Spartans were taught to suppress their desires, fears, and even basic needs for the sake of the state. Meals were intentionally bland, with the infamous black broth being a staple in the Spartan diet, emphasizing nutrition and sustenance over taste. Sleep deprivation, exposure to harsh elements, and enduring physical pain were seen as necessary sacrifices to build mental fortitude.

In retrospect, the emphasis on physical training and discipline in Sparta was both its strength and its Achilles’ heel. While it churned out some of the finest warriors the world had ever seen, it also created a society where individual desires and aspirations were constantly subsumed for collective goals. Spartans were undeniably physically superior, but this came at the cost of artistic, intellectual, and personal growth, aspects that flourished in other parts of ancient Greece.

The Helots: The Enslaved Majority and the Delicate Balance of Power

Beneath the celebrated valor and discipline of Spartan society lay a darker foundation: the Helots. They were the enslaved majority, indigenous peoples primarily from Messenia, who were subjugated by the Spartans and forced into servitude. The relationship between the Spartans and the Helots was one of dominance and dependency, a balance of power that was crucial for maintaining the Spartan way of life but was also fraught with tension and rebellion.

The sheer number of Helots in relation to Spartan citizens presented a constant security concern. Helots worked the land, ensuring the Spartans had the resources to focus exclusively on their military training and campaigns. They cultivated the fields, tended to livestock, and performed all the menial tasks that the warrior society deemed beneath them. In essence, they were the economic backbone of Sparta, producing the food and goods that sustained the city-state.

However, the Spartans were acutely aware of the potential threat posed by the Helots. To keep them in check, a series of control measures were put in place. One such method was the “Krypteia,” a rite of passage for young Spartan men. They would be sent out, armed only with knives, and tasked with assassinating any Helot deemed troublesome or capable of leading a revolt. This covert operation not only served as a form of control but also as a way to instill fear in the Helot population, reminding them of their subordinate status.

But the Helots were not always passive victims. There were instances of revolts and uprisings against their Spartan overlords. These rebellions, while mostly unsuccessful, showcased the inherent instability of the Spartan system. A society built on the subjugation of a majority could never be entirely at peace. The constant threat of rebellion from the Helots was a persistent reminder of the fragile balance of power upon which Sparta’s military dominance was built.

In sum, the Helots, often overshadowed by the grand tales of Spartan bravery and discipline, played a pivotal role in the city-state’s history. They were both the foundation upon which Sparta’s economy was built and its most significant vulnerability. The relationship between the Spartans and the Helots is a testament to the complexities and contradictions of ancient civilizations, where great achievements often came at a profound human cost.

Life in Sparta: Religion and Spirituality in Sparta

Sparta, primarily renowned for its unparalleled martial prowess and discipline, was deeply interwoven with religious beliefs and practices. In this militaristic society, the divine was seen as a guiding force, a protector in battles, and a source of wisdom for governance. While the Spartans shared many religious traditions with other Greek city-states, their interpretations and ceremonies bore a distinctively Spartan mark.

At the core of Spartan religious belief was the pantheon of Olympian gods, with particular emphasis on Apollo, Artemis, Athena, and Ares.

Apollo, associated with the ideals of physical perfection and youthful vigor, resonated with the Spartan emphasis on bodily fitness and martial readiness. The Oracle of Delphi, dedicated to Apollo, was of paramount importance. Before embarking on significant military campaigns or making critical state decisions, the Spartans often sought prophecies from this Oracle. The god’s guidance was taken seriously, and actions were adjusted based on the pronouncements from Delphi.

Artemis Orthia was another deity of significant importance, especially in the context of the famous ritual involving young Spartan boys. At her sanctuary, boys would attempt to steal cheese from the altar, all the while avoiding lashes from the priests. This ritual was both a rite of passage and a public spectacle, emphasizing physical endurance and showcasing the merging of religious rites with Spartan training.

Athena, the goddess of wisdom, was revered as the protector of the city. The annual festival of Chalcioecus honored her. But, unlike in Athens where the goddess was associated primarily with wisdom, in Sparta, she was equally revered for her strategic prowess in warfare.

The Spartans’ relationship with Ares, the god of war, was complex. While he epitomized the chaos and carnage of battle, Spartans respected his domain and sought his favor. It’s essential to note that Spartans didn’t just worship the violent aspects of Ares; they also revered the structured, disciplined side of warfare, which was more in line with their military ideals.

Outside of the major gods, ancestor worship and hero cults were also integral to Spartan spirituality. Notable Spartan kings and warriors were often deified upon death, their tombs becoming sites of veneration and their feats celebrated in songs and tales.

In conclusion, religion in Sparta was not just a private or personal affair but was deeply integrated into public life, governance, and, notably, military endeavors. The gods were seen as partners in the state’s ambitions, protectors of its people, and guides in times of uncertainty. Through festivals, rituals, and oracles, the Spartans continually reinforced their connection to the divine, underlining the interplay of faith and statecraft in their society.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!