Chinese immigrants first appeared on American soil during the late 18th and early 19th century, but in the latter half of the 19th century, they arrived in significant numbers. The California Gold Rush and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad marked pivotal moments when these immigrants, made substantial contributions. Their presence and efforts during these periods left an indelible mark on the development of the American West.

Chinese Immigrants in the California Gold Rush

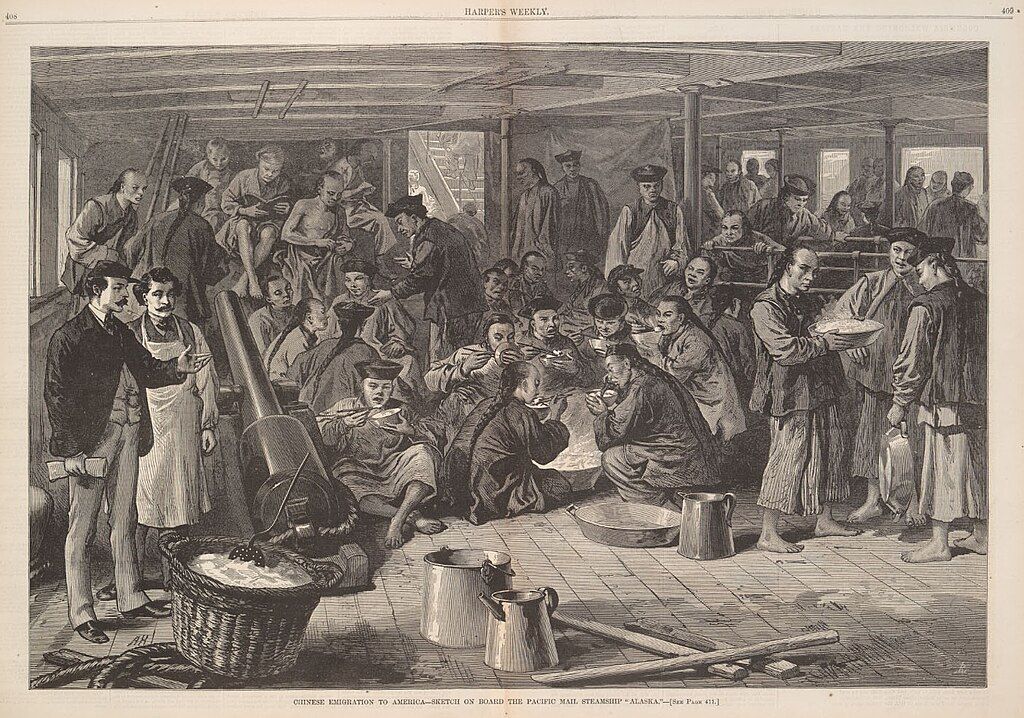

The mid-19th century marked a transformative era for Chinese immigrants, catalyzed by the allure of California’s Gold Rush and exacerbated by domestic turmoil in China. The rapid colonization of the American West during this period offered both promise and peril to these immigrants. While the Gold Rush beckoned with the promise of wealth, the political and economic instability in southern China, particularly during the Taiping Rebellion, forced many to flee their homeland. Those who ventured to America, predominantly from the chaotic Taishanese- and Cantonese-speaking regions of Guangdong province, sought not only refuge but also the chance to support their families back home through the wealth they hoped to accumulate in the goldfields.

One of the initial adventurers to seek fortune at Sutter’s Mill was a man from Canton known as Chun Ming. After striking it rich, he promptly informed his community back home, inspiring a wave of hopefuls from Canton who soon set sail towards the fabled “Gold Mountain”. The migration quickly escalated, with numbers swelling from 323 in 1849 to 450 in 1850, and a remarkable influx of 20,000 by 1852, with 2,000 arriving in a single day. These determined immigrants, carrying long bamboo poles and dressed in new cotton blouses and baggy breeches, stepped onto American shores, their feet shod in wooden soles and heads shielded by broad-brimmed hats of split bamboo, eager to carve out their fortunes.

Predominantly hailing from the farming regions of Guangdong Province, these immigrants had embarked on their arduous journey, often indebted to the Chinese credit merchants who financed their voyage. Accustomed to the rigorous demands of farming, they brought a strong work ethic and discipline, which proved advantageous in the grueling conditions of the goldfields. From dawn to dusk, they worked in large groups, a strategy that not only increased their safety against hostility but also allowed them to efficiently exploit abandoned sites left by American miners. Their resilience and collective approach enabled them to extract wealth from seemingly depleted grounds, contributing significantly to the gold mining industry while enduring the challenges of a foreign land.

The Role of Chinese Laborers in Building the Transcontinental Railroad

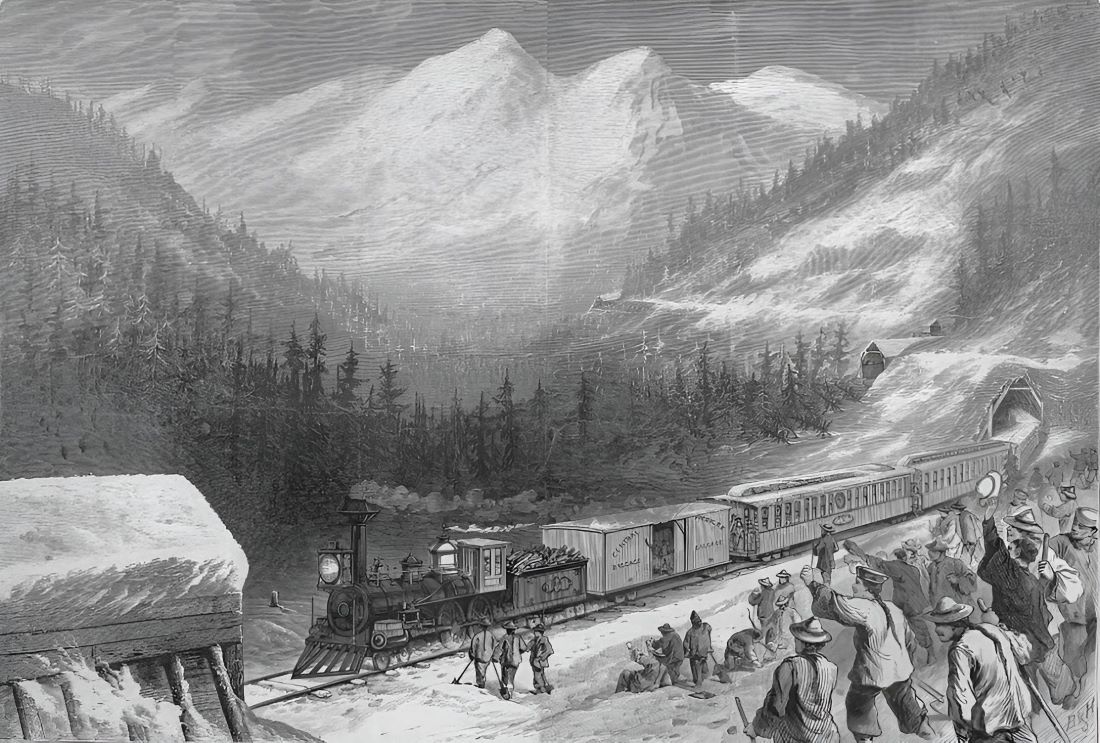

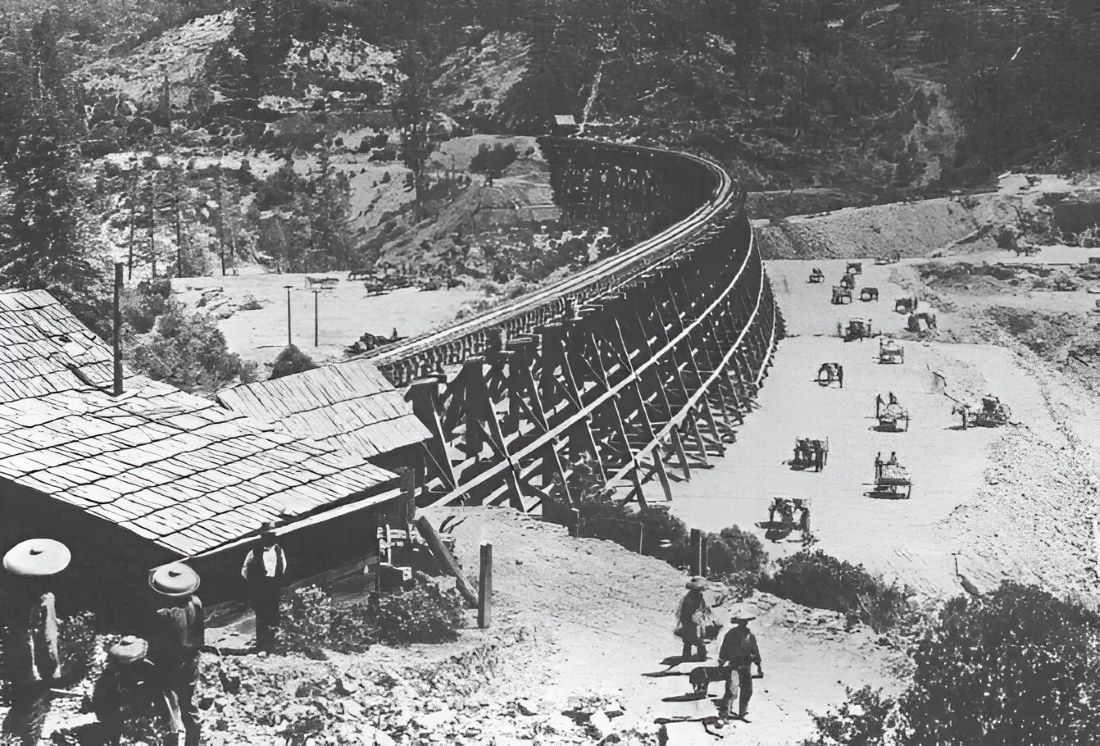

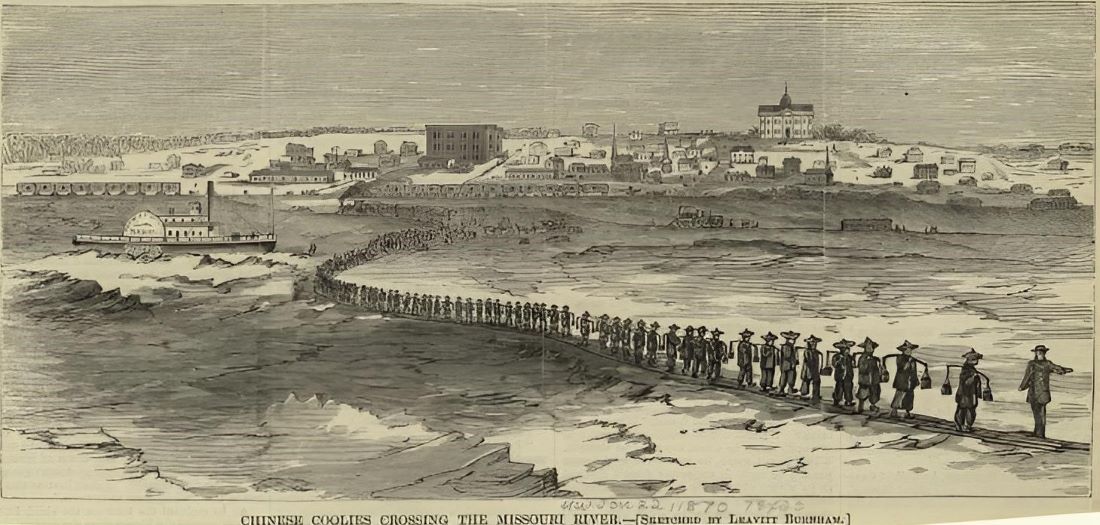

After the California Gold Rush subsided in the 1860s, many Chinese laborers transitioned from mining to railroad construction, becoming crucial to the building of the first transcontinental railroad. This monumental project started in 1863, and connected the Eastern United States with California, culminating in the “golden spike” event in 1869 at Utah’s Promontory Summit. Charles Crocker, a manager of the Central Pacific Railroad, initially struggled to convince his partners that the Chinese, often underestimated due to their appearance and derogatorily nicknamed “Crocker’s pets,” were fit for the arduous task. Yet, by employing Chinese workers, who were paid less and did not receive board or lodging, Crocker managed to keep labor costs down by a third, driving them to the brink of exhaustion but setting records in track-laying and completing the project years ahead of schedule.

The Chinese workers faced formidable challenges in constructing the Central Pacific track, including bridging rivers and canyons and tunneling through the Sierra Nevada’s solid granite using only hand tools and black powder. Their conditions were harsh, with work continuing through extreme heat and bitter winter cold, sometimes leading to entire camps being buried under avalanches. Despite these trials, the Chinese laborers proved to be highly industrious and efficient. By the peak of construction, over 11,000 Chinese were employed, forming the majority of the workforce. Their resilience and efficiency eventually earned the respect of Central Pacific officials, who appreciated their cleanliness and reliability, even as they faced widespread discrimination and violence outside their work.

Struggles and Adaptations of 19th-Century Chinese Immigrants

In the latter half of the 19th century, Chinese immigrants in America faced severe forms of discrimination that deeply affected their social and family lives. Many of these men were married, but their wives often remained in China due to cultural customs and, after 1875, American legal restrictions, leading to a poignant term: “living widows.” While these immigrants were pivotal in constructing the transcontinental railroads during the 1860s-90s, their willingness to work long hours for low wages and their racial identity led to widespread opposition.

This hostility manifested in violent riots that devastated Chinatowns from Los Angeles to Denver, with numerous Chinese killed. State and local laws further marginalized them, denying them the right to own land, work in certain industries like mining, and even testify in court. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, a landmark in restricting free immigration, drastically reduced their population, leading to a drop from 125,000 to fewer than 60,000 by 1930, with most confined to urban Chinatowns and engaged in service roles.

Amid these adversities, Chinese immigrants found ways to integrate and adapt. In many states, it was more common for Chinese men to marry non-white women, often due to anti-miscegenation laws targeting relationships with white women. For instance, in 1880 Louisiana, a significant percentage of Chinese American men were married to African American women. In Mississippi, between 20% and 30% of Chinese men married Black women before 1940. These cross-cultural unions were often kept secret or conducted outside formal legal recognition. The repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, during World War II when China was an ally of the United States, marked a turning point, yet the deep-rooted challenges and resilience of the Chinese community continued to shape their American journey.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!