The Ghana Empire was one of the earliest medieval empires in West Africa, flourishing from shortly after 500 CE until the late 12th century. Located in the western part of the savanna region, this powerful state lay far north of what is now known as the Republic of Ghana, a name adopted in homage to this historic kingdom but geographically distinct, situated hundreds of miles southeast along the Atlantic coast. The Soninke people predominantly inhabited the empire, part of the broader Mande group, who referred to their homeland as Wagadu. The strategic positioning of Ghana allowed it to thrive as a nexus of trade and culture, bridging the Saharan and sub-Saharan worlds.

Ghana Empire and the Medieval Sahara

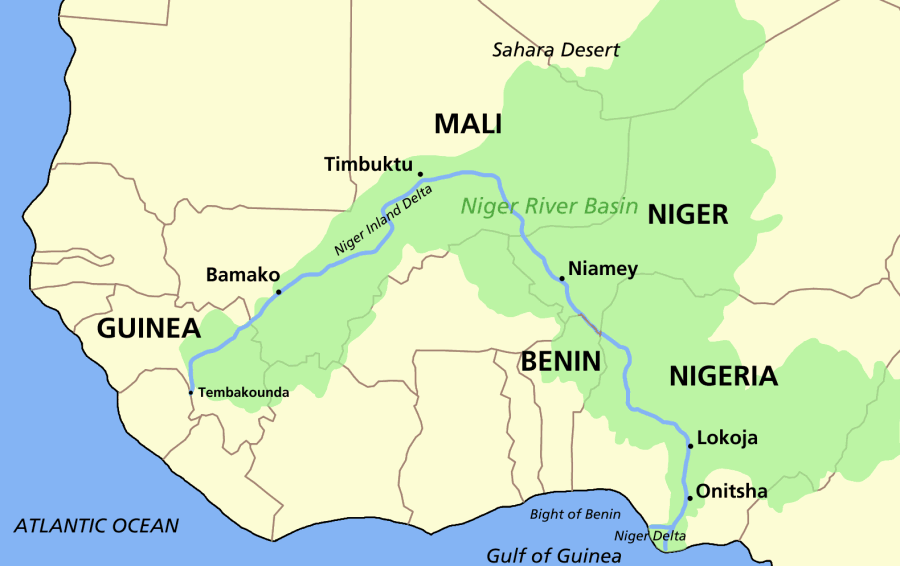

The Ghana Empire once thrived in a landscape dramatically different from the present-day Sahara, known as the world’s largest desert. This empire was strategically located at the southern fringe of the Sahara, in an area known as the Sahel, which transitions from arid desert to more fertile savannas. Historically, the Sahel enjoyed a wetter climate, particularly from about 1000 BCE to 1000 CE, enabling it to support a variety of livelihoods from cattle herding to agriculture. The region, lush and vibrant, fostered the emergence of the Ghana Empire, capitalizing on the abundance of resources and the strategic benefits provided by the nearby Niger River, the second-longest river in Africa, which has been a cradle of civilization much like the Nile.

In medieval times, the Sahel was not the semi-arid region it is today, but a vibrant area with enough rainfall to sustain grasslands and fertile soils, suitable for grazing and agriculture. The prosperity of the Ghana Empire was closely linked to its ability to produce surplus food, which supported urban populations and facilitated trade across the region. The Niger River and its tributaries formed the backbone of this ancient economy, providing water, and transportation routes, and supporting diverse communities of fishermen, hunters, and farmers. This historical narrative contrasts sharply with today’s harsh, arid conditions in the Sahara and Sahel, illustrating a profound environmental transformation over the centuries.

Historical Glimpses of the Ghana Empire

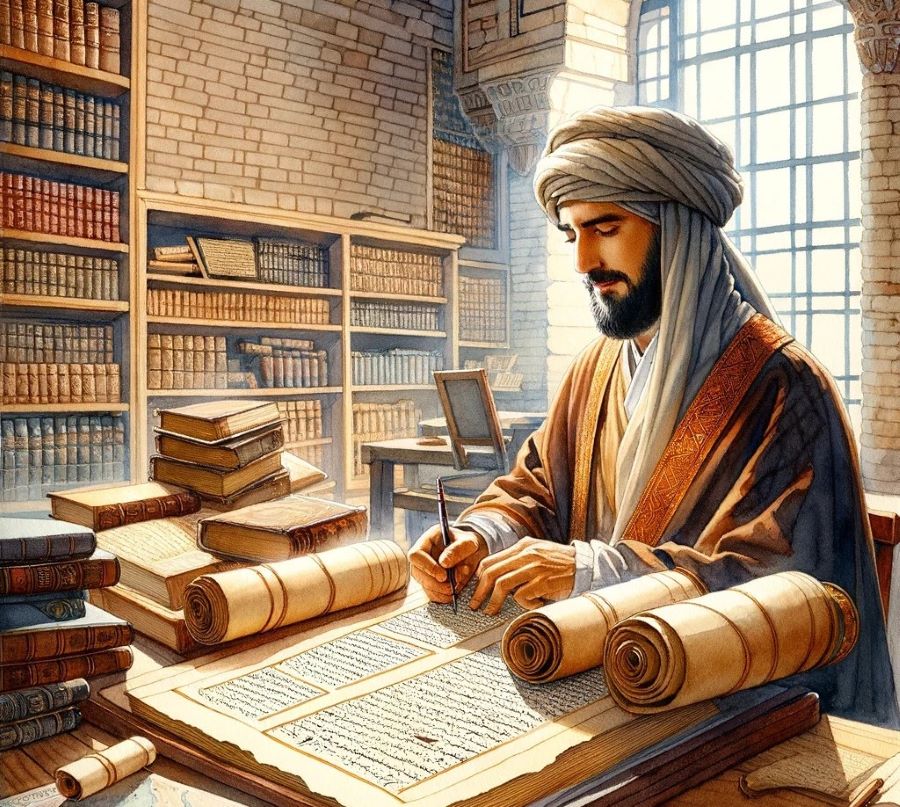

The historical records of the Ghana Empire, especially before the 9th century, are notably sparse due to the absence of a developed script by the Soninke people of the empire. Much of what is known about this early West African state has been reconstructed from Arab writings, archaeological findings, and oral traditions. Arab historians began to provide more substantial accounts of the empire starting in the 9th century, depicting Ghana as a significant nexus in the trans-Saharan trade network.

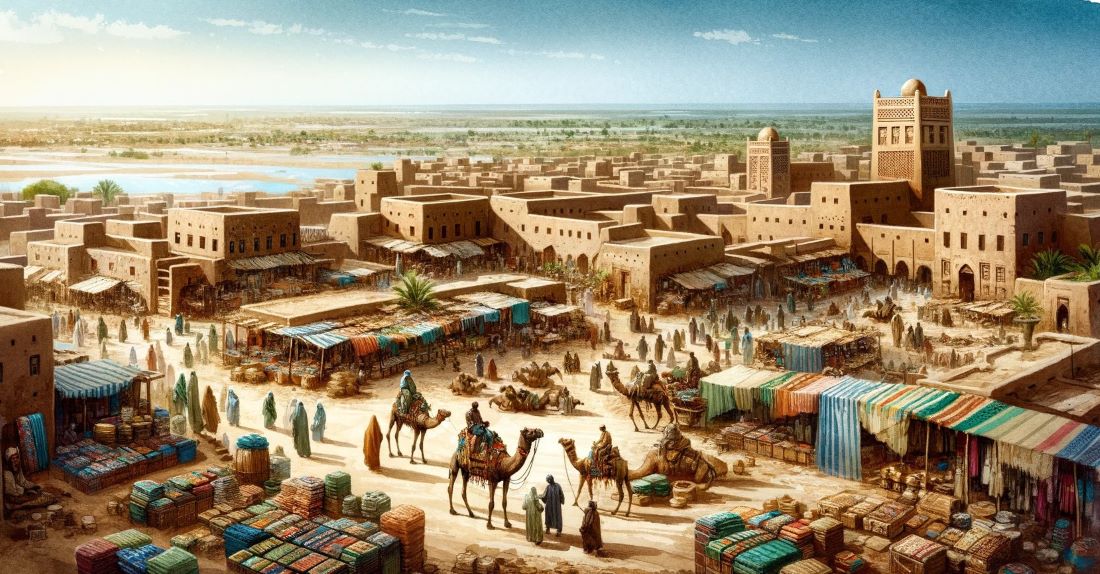

Kumbi-Saleh, the capital of Ghana, exemplified the wealth and commercial prowess of the empire. It was one of West Africa’s wealthiest cities and a major commercial hub, facilitating the exchange of goods such as gold, kola nuts, and slaves from sub-Saharan Africa with North African products like salt, horses, and silk. This barter system underscored the sophisticated economic structures that sustained the empire’s growth. Arab and Berber traders played crucial roles, acting through Soninke agents who not only facilitated trade but also ensured smooth diplomatic relations with Ghana’s rulers. These interactions were carefully orchestrated, with gifts to the monarchs ensuring non-interference in trade activities.

Despite the Ghanian monarchs’ initial adherence to traditional religions, they demonstrated remarkable religious tolerance by allowing the construction of a mosque near the royal palace for Muslim ambassadors and civil servants, who were instrumental in maintaining the empire’s connections with the Arab world. This openness to cultural and religious influences was a testament to the empire’s sophisticated governance.

The matrilineal system of inheritance, where the throne passed through the mother’s lineage, highlights the empire’s distinct social structure and women’s significant role within it. The decline of Ghana began with the Almoravid invasion in 1076 CE, which significantly weakened the empire, paving the way for its eventual absorption into the larger and wealthier Mali Empire. This historical trajectory from a flourishing trade center to a conquest highlights medieval West African empires’ dynamic and often volatile nature.

Ghana Empire through the Eyes of Arab Writers

Arab geographers and historians have long portrayed the Ghana Empire as a land of immense wealth and mystery, significantly shaping its reputation within the Muslim world. These accounts offer invaluable insights into the empire’s historical significance and its perceived grandeur.

For instance, Muhammad ibn Hawqal, a 10th-century Arab geographer, vividly described the Ghanaian ruler:

“The ruler of Ghana is the wealthiest king on the face of the earth because of his treasures and stocks of gold extracted in olden times for his predecessors and himself.”

This depiction not only highlights the abundant resources of Ghana but also underscores the empire’s established wealth accumulation practices over generations.

Yaqut al-Hamawi, another influential geographer, emphasized Ghana’s crucial role in regional trade by stating,

“Merchants meet in Ghana and from there one enters the arid wastes towards the land of Gold. Were it not for Ghana, this journey would be impossible because the land of Gold is in a place isolated from the west in the land of the Sudan. From Ghana, the merchants take provisions on the way to the land of Gold.”

These observations reflect Ghana’s strategic importance as a trading hub that facilitated not only commerce but also the survival of traders venturing into the challenging terrains en route to gold-rich areas.

Arab writers often indulged in fantastical descriptions of the wealth in Ghana, which although exaggerated, highlight the allure Ghana held in the imagination of the medieval Muslim world. For example, Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadhani suggested that in Ghana,

“gold grows in the sand as carrots do, and is plucked at sunrise.”

Similarly, the anonymous author of Akhbar al-Zaman claimed that the earth in Ghana was so rich in gold that traders could melt it directly from the ground. These tales, while mythical, underscore the mystical and exotic appeal of Ghana to the Arab world, painting it as a land where wealth was both immense and easily accessible. Such narratives played a pivotal role in cementing Ghana’s legendary status across distant cultures and continue to fascinate scholars and historians today.

Historical Challenge: Can You Conquer the Past?

Answer more than 18 questions correctly, and you will win a copy of History Chronicles Magazine Vol 1! Take our interactive history quiz now and put your knowledge to the test!